The second time I meet Vanessa Andreotti, we’re in the lobby of a Paris hotel. There are signs warning guests against trying to get around by taxi. It’s Saturday, 1st December, 2018 – or Act III, according to the calendar of the gilets jaunes protesters who are converging on the capital for the third weekend in a row, bringing half the city to a halt.

We’re here for the Plurality University, a gathering of designers and thinkers and sci-fi writers brought together ‘to broaden the scope of thinkable futures’. There are distant sirens and smoke rising from the city below, and it feels like the future already arrived while we were busy looking the other way. So Vanessa and I slip away through the back streets, talking about what happens when the future fails. She’s just been back to Brazil, her home country, and she traces the lines that run from an eruption of anger that spilled out onto the streets there five years earlier to the election of Jair Bolsonaro. How much of today’s politics, around the world, is shaped by the dawning recognition that the ship of modernity – sailing under the flags of development and progress – is going down?

‘A lot depends,’ she says, ‘on whether people feel that the promises were broken, or whether they see that these were false promises all along.’

The first step is an admission that something has gone badly wrong. This is the advantage that Trump had over Clinton, or the Brexiteers over the Remainers: whatever pile of lies they served it up with, they were able to admit that the ship is in trouble, while their opponents went on insisting that we were sailing towards the promised destination. In Brazil, the promise was that everyone could have the lifestyle of a new global middle class – and when this future failed to materialise, Bolsonaro was able to ride the anger of voters by claiming that it could have been theirs, if it hadn’t been for the corruption of his opponents. If the promises were broken, then we look for who to blame and how to take revenge. A lot depends, then, on the recognition that the promises could never have been kept; that they were not only unrealistic, but harmful. For only with this recognition is there a chance of working out what remains, what might be done, starting from the wreckage in which we find ourselves.

For more than ten years, I have been seeking out conversations about what remains, looking for people with whom to think about the wrecked promises of modernity, ways of naming our situation and making it possible to talk together about it. The most illuminating of these encounters have been with people whose thinking was formed by finding themselves and their communities on the hard end of the processes of modernisation. As Gustavo Esteva and I discussed in Dark Mountain: Issue 4, there is a sense that the West is belatedly coming to know the shadows of development and progress, shadows all-too-familiar to those unto whom development was done.

Vanessa Andreotti’s work deals with these shadows. Her institutional position at the University of British Columbia overlaps with her work as part of Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures, a collaboration between academics, artists and indigenous scholars and communities. Six months on from that day in Paris, we record a conversation, and as I listen back to the recording, I’m struck by the sense that she is always speaking out of a collective, collaborative, ongoing process of thinking together. Every time we talk, there are new versions of the ‘social cartographies’, poetic maps that make it possible to have difficult conversations. The maps that emerge from Vanessa’s collaborations are boundary objects, places where we meet, where there is a chance of sitting with our discomfort, with our limits, maybe beginning to find a place within a world that is larger and stranger than that allowed for in the ways of seeing that shaped the modern world.

DH — Looking back at the Dark Mountain Manifesto, there’s a passage towards the end where we talk about ‘redrawing the maps’, a theme I’ve found myself returning to regularly over the past decade. The drawing of maps is full of colonial echoes, so we talk about seeking the kind of maps that are ‘sketched in the dust with a stick, washed away by the next rain’. It’s this image of maps that are explicitly provisional and not pretending to the objective, detached, view-from-above quality that mapping often implies.

That makes me think of what you call a ‘social cartography’ and the collection of maps that you’ve built up with your collaborators. Maybe a good place to start is to ask just what this way of mapping means to you?

VA — You mentioned the colonial approaches to knowledge production, and I think we started there, with an intention to interrupt this totalising relationship with knowledge. In the work of the collective, we felt that maps – as images that could visibilise or invisibilise certain things – had the potential not to represent reality but to create metaphors. We wanted to create spaces for difficult conversations where relationships didn’t fall apart – and the cartographies have been our main tool for working through the difficulties, the hotspots, the tensions, the paradoxes and the contradictions of these conversations.

So, for example, we have the cartography of ‘the house modernity built’ which is talking about the fundamental structure of modernity. There are two carrying walls and there is a roof that is structurally damaged, which is why the house is unstable, facing imminent collapse.

We talk about the foundation of the house being the assumption of separability between humans and what we call ‘nature’. That separation then generates other types of separation, creating hierarchies between humans, and between humans and other species, and this is our understanding of the foundation of colonialism. In the collective, we don’t see colonialism as just the expansion of territory or the subjugation of people; we believe it starts with this foundational separability that interrupts the sense of entanglement of everything, that interrupts the sense that we are part of a metabolism that is the planet and that we belong to a much wider temporality within this metabolism. This separation takes away the intrinsic value of life within a wider whole and creates a situation where we are forced to participate in specific economies within modernity in order to produce value to ‘prove’ that we deserve to be alive.

In the image of the house, one of the carrying walls is the carrying wall of the Enlightenment, or what we refer to as universal reason – this idea of a totalising, universalising form of rationality that wants to reduce being to knowing, that then creates a single story of progress, development and human evolution. The other carrying wall is the carrying wall of the nation state, which is often presented as a benevolent institution, but was primarily created to protect capital.

The current roof of the house is the roof of financial shareholder capitalism, which is different from industrial capitalism. We talk about the differences between the two in terms of the possibility of tracing investments and of using the state as a means of both redistribution and some form of checks on capital.

DH — The way the state used to act as a stabilising force within the system?

VA — Yes, so now we have a speculative financial system where those checks and balances are eroded and where investment is at the expense of others. This investment in destruction is so normalised that even people fighting against climate change or for social justice end up not realising that by using a credit card – or by thinking about the continuity of, for example, our own pensions – we are participating in an economy that is primarily grounded on anonymity and destruction. So there is no way anybody participating in this economy can be innocent, whereas with industrial capitalism, it was much easier to trace the responsibilities: Ford as a manufacturer was embodied in Henry Ford, a person, where it was possible to say, ‘You have responsibilities in relation to society, in relation to your employees’. Today, Ford is a shareholder company and I don’t know if my pension contributions are already invested there, giving me a shareholder interest.

I’m trying to make it simple enough, without losing the complexity of the connections between these things – because I think what these cartographies do is to connect dots in a way that works against our unconscious desires to not talk about the ways we are complicit in harm.

DH — You said that a map like this is not claiming to represent reality, it’s offering a metaphor – and that reminded me of a thought about language that I found really helpful in one of your texts. It’s a two-fold distinction about what’s going on when we use language: one of which is an assumption that an objective description is being made, and the other is that language is always an action within the world, rather than a description of the world from above.

VA — In this sense language mobilises realities. So instead of trying to index reality and meaning with a view to this totalising knowledge that can control reality and engineer something, what we do is see language as an entity that plays with us and we play with it. So the relationship with language becomes very different – and that’s why also, with the maps, they move and they do what they need to do and they need to change, because they are affectable by the world and by how people interact with them.

We see that some of the maps are more stable than others because they are useful for more contexts, up to a point, but they can’t become canonical answers to universal problems. The keeping of the artificiality is really important, I think, because then it draws the attention to the process. It makes it an ongoing movement rather than an accurate description.

DH — So going back to the cartography of the house – and the impossibility of not being tangled up with the systems that are perpetrating the destruction – that’s clearly part of what you’re trying to render visible, which makes for more difficult conversations than the ones that people often want to have. I feel like one of the reasons people shy away from those conversations is because they don’t know what to do if they let all this stuff in. It’s like a pit of despair opening before them – and so it’s easier to go off and have a conversation over here, where we’ve got some simplified version of the future and of how the world is, that allows us to talk as if we had a chance of setting things right.

Letting go of that is both vertiginously frightening for people – it’s like looking off a cliff – and it’s also highly moralised. The terrible thing that Paul and I were accused of in the early days of Dark Mountain was ‘giving up’, and that’s about giving up on the stories of progress, giving up the teleological sense of direction and the possibility of mastery. So I’m interested in your experiences of what happens as we create and hold spaces of conversation beyond reform, beyond revolution, beyond any kind of promise of the direction of history.

VA — I think the giving up of illusions and seeing disillusionment as a generative thing, this is what we’ve been looking at. As you said, modernity is falling and we need to create spaces for things to fall apart generatively. Partly these are the connections that need to be made through the cartographies. Partly it’s about supporting people to work through denial. In this sense, we have been talking about three denials.

The first is the denial of violence: this house, this system that rewards us and gives us enjoyment and security, was created through violence and it is maintained by violence. So there’s an illusion of innocence and a denial of systemic violence that needs to go. Then there’s an illusion about linear progress and the possibility of continuity, this is the denial of the limits of the planet. The third denial is the denial of entanglement. We are not separated from the metabolism that is the planet, but there’s an illusion of separation – from land, from other beings, from each other, and even within ourselves, from the complexities of our own being. Once you start connecting these three illusions together, there is a falling apart. There’s also a sense that if you can’t do anything that leads to something in a teleological way, you’re not doing anything.

This structure of modernity has created a feedback loop that starts with fears: a fear of chaos, a fear of loss, a fear of death, a fear of pain, a fear of pointlessness, worthlessness and meaninglessness that then become allocated desires for specific things. So for example, the fear of scarcity becomes a desire for accumulation. And then these desires, within the modern structures and feedback loops, become entitlements: the desire for accumulation becomes, in turn, a perceived entitlement to property or ownership.

There are several of these feedback loops that make it very difficult for us to imagine anything otherwise or feel secure in embarking on things that could emerge, but that are unfamiliar and that don’t feed the feedback loops. At this point, we talk about the grammar of modernity, what makes things legible within modernity. Because of the reduction of being to knowing, legibility and the idea that reality can be indexed is what provides security. So from there we ask: what is the grammar that makes things legible and thus the only things that become real and ideal? If you want to put the world in a box, what is the size of this box and is it a square box? How does the world need to be, in order to be contained in this box? So we talk about illegibilities: things that are viable, but unimaginable, unthinkable within this grammar.

DH — Possibilities that can’t be seen through these lenses.

VA — Yes – and because we’re working with indigenous knowledge systems, or systems of being, we talk about the problems of trying to graft these systems into the same boxes we are used to. In that sense, we talk about what’s invisibilised. And there’s a need for not trying to make this visible. You need to make what’s invisible visibly absent first; otherwise, what you’re doing is just a translation into the grammar that you already have. We talk about exiled capacities, which are neurobiological states that may offer different kinds of security or stability, even without having a formalised notion of security. These could help us be together without the need to mediate our relationships in articulated knowledge. Through modernity, we relate to each other through knowledge filters, which makes sense to its grammar – but there are other possibilities for relationship, where these knowledge filters are not as important or as thick as we have been socialised into wanting.

If we are not well in our relationship first with where we are – not just in geographical terms, but in a broader sense – there’s no chance we’re going to be able to have healthy one-on-one relationships. We need to be there and then through the unknowability – because there is not a knowing place, it’s a being place – through the unknowability of this being there is where you can connect with other people. So first, you relate through a vital compass, a compass of vitality. Then you have a more intellectual compass that works with it, but is not more important.

DH — That image of a compass of vitality, it makes me think of Ivan Illich talking about conviviality and placing that emphasis on certain ways of being together, coming alive together.

VA — That’s definitely part of it, but this vitality is not just human. It’s through the perception of vitality in everything, the unknowable vitality, that we sense our entanglement with the world.

Suely Rolnik also talks about the vital compass, about how we are being fertilised by the world in unmediated ways, all the time; some gestations come to term, others do not. She talks about the fact that our vital compass is not being given space or developed, so we are having a lot of abortions of possibilities. This is because we want the moral compass to be the only mediator of reality, and this compass is broken.

DH — Wow, what a powerful set of images.

VA — I know! The abortion of possibilities really struck me… I suppose it’s true because if you are afraid of engaging with the world in an unmediated way, you’re not going to allow most gestations to come to term. You want to have autonomy and control over the life that you perceive to be only yours.

DH — There’s a conversation I’ve had with various people about steering by a sense of what you come alive to – and learning to trust, to pay attention to this subtle sense of vitality. If something is dying a little, notice that, and don’t allow anything to be so important that it overrides that awareness and the message it is bringing, the message that something is wrong. To me, this image of the vital compass speaks to that set of conversations and experiences.

VA — Suely Rolnik also has ten propositions to decolonise the unconscious. We have translated them from Portuguese in one of the collective’s publications. There are five in our version – and I think this little death you are talking about is there in those propositions.

DH — That mention of the unconscious brings me to something else I wanted to ask you about. I’ve noticed you talk about your work as a collective in terms of a form of ‘non-Western psychoanalysis’. That struck me as a very curious phrase and I’m interested to hear more about that as a framing of what you’re up to.

VA — Western psychoanalysis draws attention to the unconscious, to the desires and yearnings that drive our decisions and the ways we think. However, the ontology behind it is either anthropocentric or anthropomorphic. It’s all about bodies or archetypes. It’s useful, but it doesn’t really offer any way to manifest entanglement.

The idea, for example, that the land dreams through us is not contemplated by Western psychoanalysis – but it is contemplated by other cultures, including indigenous cultures that use psychotropics, for example, where an encounter with a being in a plant will give you dreams that you wouldn’t have otherwise. These dreams help you work through practical knowledge, knowledge of the psyche and knowledge of the divine, and there are neurological, neurobiological and neurochemical changes too. That is how it becomes neurofunctional.

If these practices are part of your lived reality, you’re talking not just about a chemistry of the brain or its biology, but its functionality: how you start to rely on these dreams, not as a different reality for an escape, but as an extension of the same reality. So we’re coming from learning about practices that do not see the body as the end, the human body – or even the human mythical frame – as the basis of existence…

DH — As the place where the thing that psychoanalytic tradition is dealing with comes to an end, the limit of the reality it can speak of. I see that.

VA — Let’s take the land as a living entity – not as a concept, but as a manifestation, because there’s a difference. A manifestation that is more powerful than just human cognition, but where humans are also part of this manifestation. If we flip that, what possibilities for being and knowing and doing and yearning are opened up? We talk about a metabolic intelligence, we’re thinking about a metabolism not only of the Earth but also of what the Earth is embedded in. In this sense, the land is not a resource or an anthropomorphic extension of ourselves, but we are an extension of the land itself.

If you turn everything to an organic metaphor, we can talk about a metabolism that we’re part of, a metabolism that is sick or that has a big constipation – a lot of shit for us to deal with! Personal shit, collective shit, historical shit, systemic shit. It needs to pass, it needs to be composted, we need to be attentive to it. This shit involves the systemic violence, the complexities of different forms of oppression, the unsustainability of what gives us enjoyment and security, and the illusion of separation. So the denials are probably the cause of the constipation.

We also talk about a ‘bio-internet’ and accessing a new operating system with new ‘apps’ or un-numbing and re-activating capacities that the house has exiled. In that sense, the engagement with indigenous practices is not about coding these practices as an alternative to modernity or as a supplement to modernity. Rather, it relates to (re)learning or (re)creating habits that can help us to figure out if we can interrupt the feedback loops (of fears, desires and perceived entitlements) of the house of modernity in order to open up possibilities that are currently unintelligible and unimaginable.

DH — That thought about the possibility of new possibilities brings me back to a phrase of yours that has stuck with me. You talk about ‘hospicing modernity and assisting with the birth of something new, undefined and potentially, but not necessarily, wiser’. After we first met, I was teaching on the first course at a school called HOME, and those words of yours became a touchstone for that week. Afterwards, a guy who was there wrote an article for VICE and hung his whole piece on those words – except that, firstly, he managed to write you out of the story and just ascribe the words to me, and then he left out the second half, the part about the birth of something new.

What I find striking is that this language of ‘hospicing’ gets used quite a lot in some of the places and conversations that cross paths with Dark Mountain. However, the other half, the assisting with the birth of something new, is often missing in those conversations. Part of that comes, I suspect, from an inability to see much space in between the end of modernity and the end of everything.

I guess that’s what Paul and I were trying to name in the Manifesto, when we wrote that ‘The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop.’ Then, a couple of years later, in a conversation with David Abram for our second book, I stumbled on a further iteration of that thought: ‘the end of the world as we know it is also the end of a way of knowing the world.’ That feels to me like somewhere you’ve been spending a lot of time, finding language for that.

VA — I think it goes back to the grammar and the feedback loops, too. So there is this desire for certainty, predictability and totalisation, right? You need to know where you’re going, even if it’s extinction! It gives you some security. So how do we open up and interrupt these desires in ways that allow us to take an integrative step into the metabolism, allowing the metabolism itself to show us the way through the vital compass that then recalibrates our intellectual compass.

It’s very interesting that everywhere I speak about hospicing, there’s always a very strong normative desire for humans to create the new reality. It’s this archetype of agency that is extremely ingrained: the idea that we can create something, and then the lack of faith in humanity to create it, which then plays into this sense of resignation. People say ‘Well, I don’t believe we can do it’, and that’s it.

What we are trying to get at is that the death we are talking about is an interruption of the totalisation. If it is about a move of integration, a move towards entanglement, towards the metabolism itself, then it’s the metabolism that does the dreaming and the creation. That’s why we don’t say ‘creating’ something new, we say ‘assisting with the birth’ of something new. We are assistants to it, we are not the ones doing it.

DH — So it’s a humbler role that we might be arriving into, if we’re lucky?

VA — Absolutely. And it’s very different from this bravado thing about saving the Earth or saving humanity or even saving ourselves or our families, prepping for the end of the world. Existentially, it’s a very different starting point. It’s not even about letting go of the ego, it’s shifting existential direction rather than focusing on form: that’s why we don’t use the word ‘transformation’.

We are interested in the shift of direction from the neurobiological wiring of separability that has sustained the house of modernity to the neurofunctional manifestation of a form of responsibility ‘before will’, towards integrative entanglement with everything: ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’. This form of responsibility is driven by the vital compass. It is not an intellectual choice nor is it dependent on convenience, conviction, virtue posturing, martyrdom or sacrifice. You can see this responsibility at work in practices of indigenous and Afro-descendent communities that collaborate with the collective.(1) We have been working on the question of how to invite the interruption of the three denials and the composting of our collective and individual ‘shit’ in non-coercive, experiential ways.(2)

Notes

(1) See bit.do/billcalhoun and bit.do/webofcures

(2) See bit.do/decolonialfuturesimpact

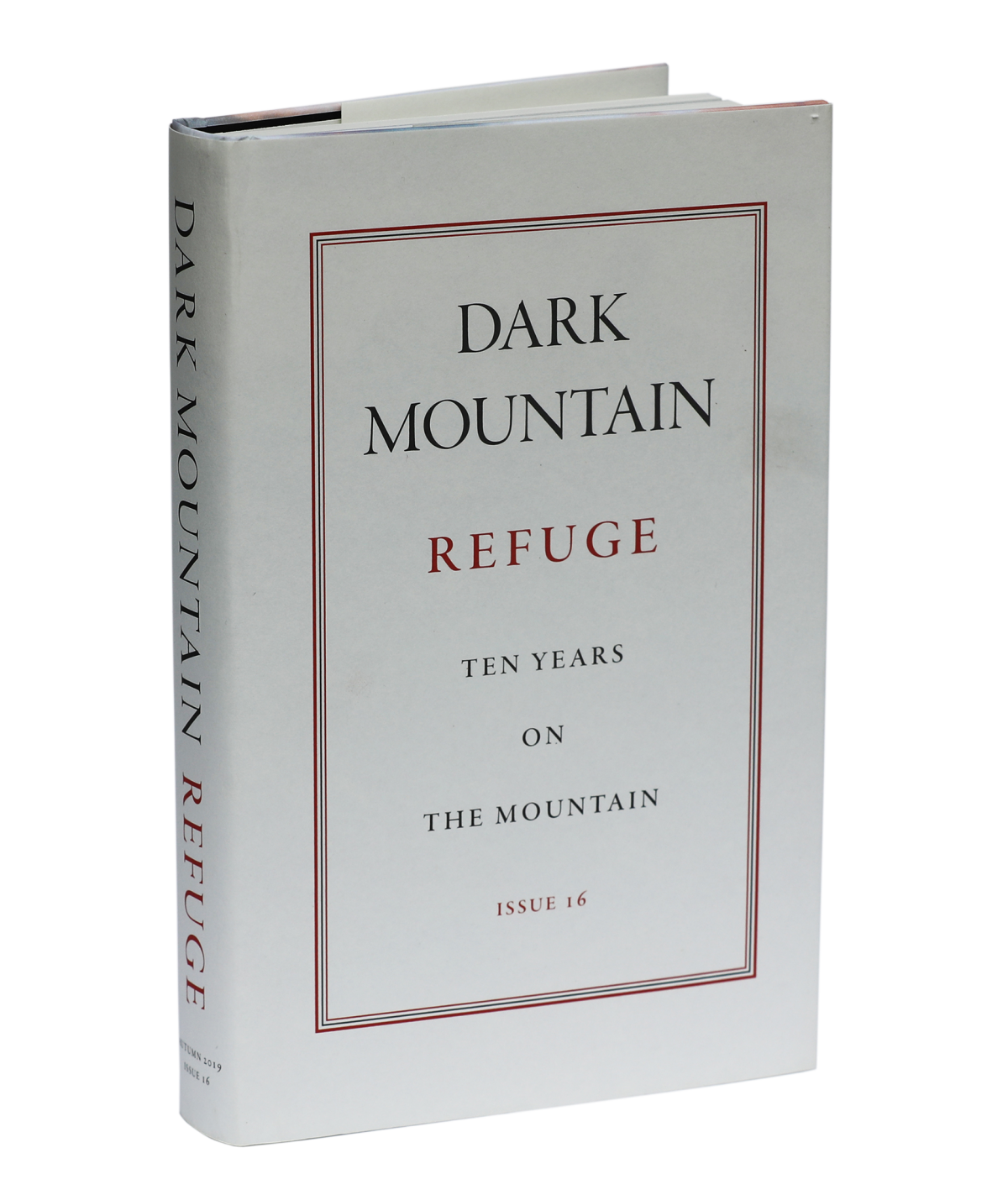

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 16 – REFUGE, a special edition to mark the tenth anniversary of the Dark Mountain Project.