A review of ‘The Anthropocene: The Human Era and How It Shapes Our Planet’ by Christian Schwägerl and ‘Adventures in the Anthropocene: A Journey to the Heart of the Planet We Made’ by Gaia Vince.

Walking aimlessly through north London, a decade ago, I was stopped in my tracks by a glowing sign that read ‘Holocene Motors’. What dark coincidence or twisted joke was this, an auto repair shop named after the geological epoch that our motorised way of life is bringing to an end?

That end is on its way to becoming official. A working group of 30 scientists will report next year to the International Commission on Stratigraphy to determine whether the Holocene – the epoch from about 10,000 years ago to the present, covering the period since the last glaciation – has been superseded by the Anthropocene: Greek for ‘the age of humans’. Meanwhile, the idea of the Anthropocene has already escaped from the laboratory of scientific discourse, into the wider social and cultural landscape, seeding art projects, philosophical symposia and newspaper op-eds. Two well-written books by experienced science journalists – one from Germany, the other based in the UK – each offer a beginner’s guide to this terrain.

Christian Schwägerl juxtaposes a history of the emergence of a scientific awareness of the planetary impact of human activity with the deep perspective of the history of the planet itself. He tells us that we have joined ‘The Club of Revolutionaries’, a shortlist of species that have created change on a geological scale, beginning with the cyanobacteria that first harnessed the Sun’s energy through photosynthesis and changed Earth’s atmosphere by doing so.

While he is convinced that it is good and necessary to think of ourselves as living in the Anthropocene, Schwägerl also takes time to acknowledge the criticisms that have been directed at this way of naming and framing our situation. Gaia Vince’s journey is more breathless, a world tour of how our transformation of the planet is playing out on the ground.

The strength of Vince’s book is that her attention is focused on the far end of the supply chains that wrap the world. She reports vividly on the destructive consequences of our way of living, but also on the grass-roots ingenuity by which people go on making life work and improvising solutions in the contexts where they find themselves, often by reviving older traditions. She visits the human-made glaciers of Ladakh and the underground tankas that collect rainwater in Indian cities, banned and filled in under British colonial rule, but starting to be put to use again.

When Vince starts to put together the pieces, she has a tendency towards the rhetoric of benign technological globalisation that you hear from Google executives and TED speakers. The lack of a more careful analysis means that she often overlooks or glances only briefly at clues within the stories she is telling that might have brought the whole frame of development into question.

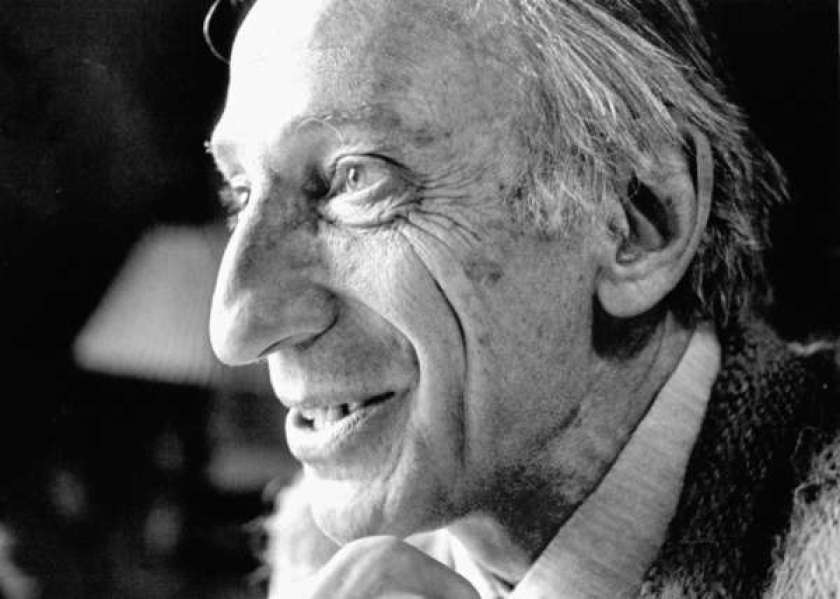

Schwägerl’s writing is more reflective. He gives a striking account of the origin of his own conviction that humanity needs the idea of the Anthropocene. “I became thoroughly despondent in 2009 during an interview with Dennis Meadows, one of the co-authors of the bestseller The Limits to Growth. After our meeting, it took me a long time to shake off the apocalyptic visions he’d evoked.” The book’s epilogue is built around a conversation with Paul Crutzen, the chemist and Nobel laureate jointly credited with having given the Anthropocene its name, in which Schwägerl keeps pushing him to agree that we need optimism rather than pessimism.

There’s an impulse at work here that is important. We do need stories that go beyond the prophecies of doom that environmentalism has often seemed to offer: not because the warnings are wrong, or because we can apply positive thinking to escape this mess we’re in, but because, bad as things may get, there will still be creatures like us, trying to make life work as best they can, for some time to come.

The attraction of the Anthropocene as an idea is that it opens up a space that is neither denial nor apocalypse. The trouble is that it is haunted by a shadow of self-congratulation, a dark heroisation of the scale of humanity’s achievement, and an elision by which the power to destroy is taken as evidence of the ability to control, steer or master. The Greeks had a word for this, too: they called it hubris, the kind of pride that comes before a fall. Whatever stories we tell, our eruption into planetary history is likely to leave us humbled, though a humbling may bring with it hidden blessings.

To think geologically is to face the overwhelming depth of time, the vastness during which nothing like us existed, and the smallness of our own place within that overall expanse. As geological epochs go, the Anthropocene looks set to be nasty, brutish and short. But, read with care, each of these books contains clues as to how we might endure and come through it.

First published in Resurgence: Issue 292.