A couple of weeks before COP21, I did an interview with an American radio station. They set me up against another guest, a professor at Yale who specialises in the psychology of climate communication. I don’t know what my credentials were meant to be, on this occasion, except that the producer said, ‘I spend a lot of time interviewing people about climate change and the things you say are the things the others only say after I’ve switched off the mic.’

The ISDN line from the broom cupboard in Stockholm where I was sitting to their studio in Chicago kept dropping out, so I only heard half of what the guy they wanted me to argue with was saying. What stuck with me was a question that came from the host. I had been talking about the lifestyles that most of us take for granted, just now, in countries like these. I said, ‘I don’t believe these lifestyles are going to be made sustainable.’ The next time the host came to me, he asked, ‘So, in this future you’re talking about, how many humans are left at the end of the century? Are we talking a hundred thousand, a million?’

The question threw me, I didn’t know how we had got here, but afterwards, as I went over the interview again, the best explanation seemed to be that he had taken my suggestion that the lifestyle of the western middle classes is going away and equated this to the elimination of 99.99% of the human species.

For ten years or so now, I have been lurking around a few of the ‘collapse’ blogs, the corners of the internet where people think out loud about the end of the world as we know it. There are sites whose authors are loudly certain that this means imminent human extinction, but the ones to which I find myself returning are written by people who are trying to think around the edges of the world we have known, to catch sight of the unknown worlds that may lie around the corner. It is easy to imagine the apocalypse – easier than to sustain the belief that things can go on like this – but what is hard is to recognise the space between the two, the messy middle ground in which we are likely to find ourselves. At its best, like certain kinds of science fiction, the writing of the collapse bloggers provides a work-out for the historical imagination.

Among these online conversations, one of the distinctive voices belongs to an American who usually writes under the name Anne Tagonist – or at her current site, More Crows Than Eagles, Anne Amnesia. Over time, I’ve been struck by the breadth of her frame of reference, but also by her willingness to puzzle through a question, sharing her uncertainties. Lately, I had noticed her picking up on posts from Tom James and Charlotte Du Cann on the Dark Mountain blog, so I got in touch to propose an interview. Thinking back over the decade since I stumbled across the collapse blog scene, and knowing that Anne has been around it longer, I started by wondering what shifts she had noticed – though, as she pointed out, the timeframe we are talking about is rather a short one.

DH: I’m curious how you found your way to this corner of the internet in the first place – and how you’ve seen it change, between then and now.

AA: I wanted to start by saying something like, ‘Growing up, I would reread Walter Miller’s Canticle for Liebowitz every autumn,’ or some such deep explanation. But anxiety about the long-term stability of a complex and interdependent lifestyle has been part of western culture since at least Tacitus. Have you read the Germania? It’s pretty clear that Tacitus was the late Roman Jim Kunstler: it’s all about what intolerant hard-asses the Germans are, completely unlike the effete and decadent Romans, and how this makes them a much more honourable people. It seems to me to be a document of a sort of self-doubt in the heart of what was still, in 98CE, the most powerful empire on the planet, worrying that too much ‘civilisation’ had sapped Roman vitality and – it’s clearly gendered in the text – manliness.

I should note that by the time the Vandals sacked Rome three hundred years later, they had become an intercontinental trade empire with bigger cities than Tacitus had even seen, so it’s up to interpretation whether he was ‘proven right’.

Anyway, the point is, people have worried that they were getting ‘too civilised’ and were risking some sort of collapse, if the interdependence implicit in cosmopolitan society were disrupted, for a very long time. Tracking my own interest is really only the story of my own life, which is why Walter Miller isn’t a bad place to start. Worth noting, though, is that I also grew up with a ‘nuclear air-raid drill’ every Wednesday at noon in my hometown. It wasn’t the much-mocked duck-and-cover, just a test to make sure the siren still worked, but the reminder of an existential threat was just as piercing as it would have been in the sixties. The library stocked civil defence pamphlets, if you wanted to know how to make a hand-powered ventilator for your underground shelter that would screen out all but the smallest fallout particles. It was just something that you learned to accept.

Canticle is a three-part story, set at different stages of future history after a nuclear war. Unlike most of the global disaster science fiction, it was less about conflict between the ‘good’ survivors and the ‘bad’ and more about how to restore a sense of dignity and meaning to a human race that now live undignified, hard-scrabble, starvation-plagued, miserable lives, and, worse, has brought this condition on itself through hubris and self-destruction. It’s a very Catholic book, obviously: how do you exalt the fallen?

I think that’s still the contradiction that runs through my own writing: we are prone to horrible rages and self-destruction, and yet we are still beautiful and imaginative and worth loving. We have fucked up pretty much every part of our ecosystem worth up-fucking, and yet we are the only species we have the option of being. We are both fragile and indestructible, stupid and self-sacrificing, fear-shot and able to party in the ruins of any catastrophe. What do you even do about that?

I was a zine writer and a traveller, and somebody swapped me a copy of Evil Twin’s Not For Rent just before the US got its first road occupation, in Minnehaha, Minneapolis. So of course I had to go. It was back just before the WTO protests in Seattle, and John Zerzan and Live Wild or Diewere the big deal on the radical-eco scene, so that was the world I lived in. The Y2K bug pushed a lot of people to imagine what would happen without computers, and living as we did in an extremely improvisational and DIY sort of way, it was hard to see that kind of collapse as a bad thing, especially because it would probably bring an end to the paving and deforestation that we were fighting. I developed this sort of double-vision where I would see things as they ‘were’ and superimposed I would see them as they would be after a century of abandonment and neglect. I can’t explain this, it still comes over me sometimes; sometimes it’s beautiful and sometimes it’s terrifying.

I had a tense relationship with the anti-civilisation kids because, on the one hand, I helped organise a few gatherings, while on the other hand, I thought most of them were nuts. I took a road trip with one kid who kept trying to convince me that being polite to strangers was a crippling weakness induced by civilisation, and so this person was intentionally rude, all the time. There were also a few professional gadfly types who showed up, for instance, to a collective in Texas where I was living and spent a week on the couch denouncing things. The positive ‘rewilding’ lifestyle hadn’t really come together and there was no way for people to live that felt like they weren’t betraying themselves constantly, so of course they were very grouchy all the time.

I became fairly disenchanted with the anti-civ/collapse idea in Texas, but two things happened in rapid succession to change my outlook. First, in the July 2005 issue of The Atlantic, James Fallows wrote ‘Countdown to a Meltdown’, an article that pulled together peak oil, the housing bubble (still largely unrecognised) and a pending currency crisis that doesn’t seem to have come true. This was the most significant and official acknowledgement of the instability of ‘progress’ that I’d come across that was immediate and concrete, rather than just being a hand-wavy extension of cultural anxiety and disguised Cold War nuclear horror. It put the possibility of serious changes in the ‘American Way of Life’ back on the table.

The second event was Hurricane Katrina. After joking sarcastically on my then blog that anti-civ kids should all go down to Katrina and see what life was like without the infrastructure of a functional community, I watched several people, friends and unknowns, go do exactly that and turn what was probably the biggest disaster in the US in my lifetime into a brilliant experiment in post-collapse living. The punk/squatter scene in New Orleans before the storm was more notable for axe fights and really bad drunkenness and suddenly, with a shared purpose, those same kids started improvising electrification schemes for storm-damaged neighbourhoods and building out community-run infrastructure. It made me rethink my cynicism about anti-civ activism. I now think that in the absence of civilisation, most people – perhaps not anti-civ activists, but that’s another story – would be helping improve the lot of strangers and would recreate the best parts of a society to the best of their ability.

Seeing this happen mellowed me a lot to the new generation of collapse writers, at least to those who weren’t daydreaming about shooting their neighbours at the first sign of currency depreciation. I found Ran Prieur’s blog when another collective I was living in, this time in Philadelphia, was looking into growing edible algae on the roof. He had written about a book that he’d been unable to track down on microalgae, and my college library had a copy. So I read it, sent him a review, and we’ve been trading emails ever since. Having Ran and his readership to interact with made me more comfortable with writing collapse-y articles for a general audience.

DH: Reading this, I got a string of flashbacks. To being eight years old and finding out about nuclear weapons and wondering why all the adults seemed to be going on with their lives, acting normal, as if this wasn’t the most important and horrifying thing ever. (I wonder if kids still have that now, when they learn about the missiles in their silos, or if it was specific to the Cold War and the explicit promise of Mutually Assured Destruction?) And then to being twenty and reading about Y2K, the sensation of vertigo, that the world as we know it might just end. As I turned this possibility over in my head, wondering what to do with it, another thought came – that everything is going to end, sooner or later, anyway, from one chain of events or another. I remember this as a weirdly comforting realisation.

The way you describe your trajectory, it sounds like you came across the anti-civilisation and collapse stuff within a whole context of zines, activism, punk, DIY culture. On this side of the Atlantic, it seemed to be less grounded, something I came across late at night on blogs written by people I’d probably never meet, or through books by Zerzan and Jensen. When Paul and I wrote the manifesto and called it Uncivilisation, we were thinking on slightly different lines – not so much ‘anti-’ some big other of civilisation, more how do we start disentangling our thoughts and hopes from all these illusions and grand narratives – but one effect was to create a meeting point where people who were trying to figure this stuff out could find each other, including getting together around festival campfires and having conversations that there didn’t seem to be room for in the activist spaces that a lot of us had been involved in.

One thing that’s troubled me over time, and you touched on this already with Tacitus and the Germans, is how male and white and straight the perspective of most of the writing about collapse tends to be. Not that this is in any way different to the perspectives that get most of the attention on almost any other subject, but still, it distorts the way this stuff gets talked about. I remember Vinay Gupta coming to the first Dark Mountain festival, looking out at this very white audience, and saying, ‘What you people call collapse is living in the same conditions as the people who grow your coffee.’ And I’m thinking of a post of yours about ‘Poverty, Wealth and the Future’, where you wrote, ‘Your meditation for today is this: Who would you be in a refugee camp?’ I keep coming back to that post.

So I wonder if you could say some more about the way those distortions shape the tropes of collapse writing, and what it might mean to ground our thinking in a broader range of human experience?

AA: Well, it’s interesting to read your question about the persistence of the nuclear threat on the same day that I learn about a ‘mishap’ with an intercontinental ballistic missile in May of 2014. I’m not sure it still has the same emotional resonance that it did in my own childhood, but we’re stuck for the foreseeable future living in a world where a dropped wrench can potentially end the planet. I’d be interested to ask young people how often they worry about this sort of thing – it’s probably important that in my childhood (and yours, it sounds like) nuclear annihilation would have been a deliberate action by a hostile agency, rather than a stupid mistake. I think we have an easier time psychologically facing down an opponent, no matter how implacable or even incomprehensible, than we do confronting random chance and tragic error.

You’re definitely right that my own development as a ‘collapse’ writer happened socially, rather than in isolation, but I don’t know whether that’s common or not. The internet would suggest that the typical apocalypse fan came by their beliefs consuming media alone, and in fact tries to hide their ‘preparation’ from their friends and neighbours, either because they don’t want to be besieged by hungry zombies when the shit hits the fan or because they’re embarrassed to subscribe to a philosophy that treats their nearest and dearest as a zombie-level liability in need of murdering some time in the near future. Then again, isolated angry people tend to make up a disproportionately large part of any internet conversation, so I’m not sure whether this is actually a relevant metric.

I think this gets to what you’re saying about one person’s collapse being someone else’s daily life. There’s a meme that crops up whenever there’s a major disaster anywhere in the world: American journalists report back from the scene, bewildered at the ‘resilience’ of the local population, who are struggling onward, getting out of bed and tending to things on schedule, despite the horror that has befallen them. Having seen disasters in the first and third worlds, I am most taken by the aspect of surprise. It’s as if the reporters assume that the natural response to an earthquake, or a coup, or an outbreak of a terrible disease is to run in circles fluttering your hands until you are too exhausted to continue, or worse yet to kill yourself.

For a long time I thought this was just the idiocy of the American journo narrative, but since Superstorm Sandy, we’ve seen several crises hit not just the US, but relatively affluent parts of the US. Surprisingly I have seen people quivering before the cameras, seemingly helpless, asking, as if the amassed TV audience were able to answer, what they are supposed to do? It struck me that this is actually not a disaster response, it’s a fear response – it’s the sort of thing people do, not when their way of life has been completely overwhelmed and they have an extended to-do list just to get through the day, but when they feel that way of life is deeply and permanently at risk, and there’s (as yet) nothing they can actually do about it. When you live in a crappy corrugated iron shed, next to a thousand other crappy corrugated iron sheds, and you walk two miles each morning before dawn to pick coffee, a flood is a crisis that demands attention, and your whole mind is full of getting the kids to high ground, waiting at line for the satellite phone to call your cousin in the city, and otherwise managing your situation. Freaking out would be counterproductive and as a rational, caring human being, you don’t. When you have a mortgaged, expensive, oversized house with flood insurance and a national guard that will make sure your family won’t die, when you have a credit card to stay at any cheap hotel in the state, when your daily social status concern is whether people like your posts on Facebook, you have the luxury to freak out, even if it is pointless to do so.

I think collapse writing, when it isn’t pathological anger, is something like a luxury freak-out. It’s about a looming fear of shame, of loss of status, loss of comfort, a return of the repressed hardships we know are entailed by our lifestyles, if not by life itself, but which we generally manage to outsource to someone else. I think this is why so many collapse narratives are moral in nature – there’s a sense that we’ve got it coming, but so far we can continue to work at our near-sinecure jobs, worry about our near-frivolous social status variations, argue about increasingly minute differences in consumption patterns (organic? paleo?) and otherwise ignore our insecurities. There’s no pile of cinderblock to be dismantled, no giant slop of mud in the cowshed, no long road to safety that we can walk, nothing, that is, to ameliorate our situation – it is as fixed and inaccessible as history itself, which is why it often seems like something that’s already happened.

As to your question about whiteness, I’d come at it from a slightly different angle. Especially since the anti-colonial renaissance of the sixties, people from the Global South have been writing passionately of their experiences losing their social structures, their way of life, their sense of self when an aspect of the natural world, or the political superstructure, or some seemingly insignificant part of ‘the economy’ rolls over and takes a crap. Why are collapse bloggers not reading these, or at least not incorporating them into their understanding of the future? Why are the experiences of the third world not considered collapse writing? Why, when you see a reference to a kinship society torn to pieces by a land-grabbing human-enslaving culture-ignoring ‘civilisation’ storming in with guns, is it always Braveheart and not, say, Chinua Achebe? Where, in all the paranoia about Ebola a few years back, was any acknowledgement of slave trade or the ivory trade or the rubber trade or any of the long history of civilisation-ending catastrophes in that exact region?

I would proffer two unflattering analyses. First, it is hard for western white people to identify with people of colour, especially poor people of colour, especially poor people of colour living outside what we think of as the west. That’s a disgrace and perhaps a damnation upon us, but it’s a bigger problem than the collapsosphere. Secondly, I think the stories from The Everybody Else don’t contain that vertiginous loss of status, that plunge from the precipice into the subaltern, and hence aren’t readily associated with the same frisson of hand-fluttering panic. These two analyses are connected of course – much of the social status in the world seems insignificant to the very wealthy, hence the popular reading of The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind as a tale of a third-world startup entrepreneur. The idea that a family who grows corn, sells cattle, and has a market stall would be the absolute last family who should be starving seems unfamiliar to a western culture where farmers, at least farmers who did not grow up on organic box cereal in Brooklyn, are assumed to be ignorant and dangerous, so readers don’t pick up on exactly how socially fraught, even shameful, the Kamkwambas’ plight actually is.

Exceptions worth mentioning are Delaney’s Dhalgren and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower which are both by and about black Americans. Underrated, I think, both of them, but still reasonably well incorporated into the collapse bibliography. Also, several science fiction books and articles about the third world, written by first-worlders, have achieved some celebrity. I’m thinking of Gardiner Harris’ work on sea-level rise and slavery in Bangladesh, Margaret Atwood’s backstory to the character Oryx in Oryx and Crake, Ian McDonald’s Chaga Sagaand Brasyl, Paolo Bacigalupi’s entire oeuvre. Still, these are observations and fictional projections, not first-hand experience, and they certainly shouldn’t substitute for the (existing) shelves full of analysis on social disruption written by subaltern populations themselves, so Vinay’s point stands.

I imagine that as more people are directly affected by climate change, in the west as well as elsewhere, first-world collapse writing – at least first-person first-world collapse writing – will become more measured, realistic, and task-saturated, plaintive in its appeals to justice but competent in its approach to the immediate future; in other words, more like the last century of third-world collapse writing. Whether this displaces status-shame-panic as a genre, or whether ‘collapse’ will continue to refer only to the terrors of the shrinking pool of people who have not yet been directly impacted by changes in the world remains to be seen.

DH: What you say about the luxury of freaking out makes me think of a conversation in the Dark Mountain Workshop here in Sweden. Two of the artists in the workshop have been studying with the same teacher, an autistic woman who had to develop her own models in order to understand the reality which people around her take for granted. These models start from the distinction between ‘the primary’, the reality of life itself, and ‘the secondary’, the reality of values, culture, a particular way of living. We need both of these, she says, but there is a danger if we treat the secondary as primary. There’s a particular ugliness, it seems to me, when we start defending our way of life as if our lives themselves were at stake. We’re seeing this in Europe, just now, as people whose lives actually are at stake – at home in Syria, on the wretched rubber dinghies crossing the Mediterranean – are greeted as a threat to our way of life, so that the Greek government is being urged by ministers from elsewhere in Europe to start sinking the boats.

Thinking about this collapsosphere that we’ve been talking about, there’s a similar confusion that runs down the middle of it. A lot of folks who are drawn to these online conversations are certainly ‘apocalypse fans’ – people for whom ‘the end of the world as we know it’ means zombies and cannibalism and fortified compounds, who read Cormac McCarthy’s The Roadas a guide to the future. But the other side – which I guess is the reason I find myself coming back, despite the ambivalence that we’ve touched on in this discussion – is that this can sometimes be a space in which people are developing a language in which to talk about the difference between ‘the end of the world as we know it’ and ‘the end of the world, full stop’. That feels interesting, maybe even useful.

One more question, before we wrap this up. Anyone who has followed your blogs will pick up that your work is related to medicine. The conversations around the collapsosphere are often intertwined with some kind of critique of progress – and the achievements of medicine and public health are often used as a trump card by those defending the idea of progress. So I’m curious what reflections you might have on how these things fit together?

AA: I worked as a ‘street medic’, then on an ambulance, and then I became a medical student before shifting gears to become a researcher. The idea that medicine and public health are ‘trump cards’ for progress is only relevant if you believe that progress (or not) is a decision being made by rational people on the basis of evidence, which it isn’t. If it were, I’d choose progress which allows everyone on earth to enjoy the actual benefits of a modern western standard of living (not losing half your kids to dysentery, seawalls, language schools and construction methods that acknowledge the inevitability of fires and earthquakes), low- to zero-consumption technology, rewilding of land, informed stewardship of agricultural areas, and continued best practices in medicine and public health –and avoids wasting any resources on the bogus fake benefits (candy, cheap long distance travel, extra clothing, jet skis, Facebook). But progress doesn’t work that way. I’m not the queen of the world and don’t want to be; I’d imagine pretty much everybody on the planet could make their own lists of which developments count as progress and which don’t; and I doubt there’d ever be any consensus. Plus, when you think about what it would take to actually create and enforce ‘rational progress’, you realise it isn’t going to happen.

That said, hell yes – you can keep your ‘man walks on moon’, I say the high point of collective human achievement is the elimination of smallpox. We’re less than five years from eradicating polio and guinea worm too.

DH: Yes, I guess where I was going with the ‘trump card’ thing is that, if you try bringing the idea of progress into question, pretty soon you will be met with an argument along the lines of, ‘Are you saying smallpox eradication, aspirin and the reduction in infant mortality aren’t real, good and important developments?’ And it’s hard to imagine a sane standpoint from which to deny the reality, goodness or importance of these things. So it seems like a fairly unanswerable argument that progress exists as an objective historical phenomenon – even if it is a phenomenon that’s vulnerable to setbacks and reverses, not an inevitable one-way force. Against this, I’d want to say that it may be wiser to attend to the specific, to celebrate these good things for what they are – whereas once we start talking in terms of progress, however carefully, this tends to become a generalised idea under the heading of which things we would want to celebrate and things we might want to question get bundled together. This is one of the senses in which progress is not ‘a decision being made by rational people’, as you say, but an intensely-charged narrative with a particular cultural history.

AA: Ran talks about this phenomenon – that people lack the imagination to picture a world other than one we’ve already lived through, so if you don’t like The Now, you must be arguing for some time in the past with all its warts and insufficiencies. There are two ways to approach this, I think: one is from an engineering perspective, explaining that just because we won’t have ubiquitous cheap energy at some point in the near future, or just because our current patterns of settlement are unlikely to persist, that doesn’t mean we’re going to forget everything we know about waterborne diseases. This is a difficult argument to make, though, because I am not a water treatment engineer and chances are neither is whoever I’m talking to, so it’s hard to avoid making wild and inaccurate claims about technology and technê.

The other approach is one that I’ve seen used to refute eugenics – imagine a future historian looking back at the early twenty-first century. Would they, in all likelihood, have any more respect for us today than we have for open-pit lead smelting and leech-doctors? Whoever comes after us will probably look at us as flawed, short-sighted and blind to the effects of our actions, just as we see our predecessors in hindsight. Their successors will view them the same way. Even if they do re-adopt older technology, or forget some aspects of ‘progress’ that are unblemished boons to humanity, they’ll still see us as morons, just as we can lament the passing of the Stick Chart or the ability to recite the Odyssey from memory, while being grateful that we don’t actually live in those worlds.

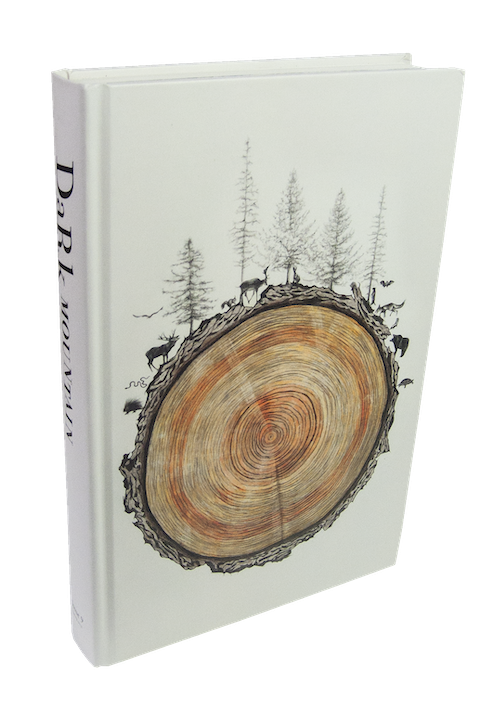

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 9.