The work of editing has its rewards: often, during that collaboration to bring into view the full richness of another’s words, I find my own thoughts clarified by insights that I might have missed, had I only read those words in passing. So it was that, six months after this conversation with Sajay Samuel – pupil and friend of Ivan Illich – I found myself editing an essay by Bridget McKenzie which would be published as “Turning for Home”. At its heart, it seemed to suggest a simple and powerful reframing of that process to which Illich invited us, more than forty years ago, of “Deschooling Society”.

The essay was a reflection on Bridget’s experience as the parent of an eleven-year-old who said no to her secondary school. To explain this decision, her daughter offered a drawing of a narrowing tunnel of time, beyond which stood skyscrapers and riot police: the world is going to get more modern and violent, she said, and the tunnel of school “would not protect her, but crush her identity and stop her from doing anything to make the world better”.

I know Bridget as someone whose voice is listened to on education – a former Head of Learning at the British Library, among much else – and yet, as she wrote in that essay, after twenty years of professional involvement with schools, the experience of home schooling her daughter was to shake her assumptions:

I had always seen a division between home as a place of comfort (if you’re lucky) and school as a necessary “outing”, a place that prepares you to go out into the world… However, I have also come to think that learning defined as “learning to work out there in the world” is a framing that is both unhelpful and untrue.

For a start, the dichotomy of home and work embedded in our culture is incredibly damaging, and does this damage not least because it seems so innocuous. The idea of separation between home and work is responsible for increasing isolation in communities and for the loss of status and confidence of many people with home-based lives […]

When most of us push off from home into the world of work, we enter an industrial system that is antithetical to the living world. We enter places that are abstracted from our planet home, represented in the dislocated nature of workplaces and effected in the systematic commodification of the planet’s resources.

While editing these passages, the thought came to me: would Illich have been better understood if the book for which he was best known had been titled, instead, Rehoming Society? For our school systems were not his particular obsession: rather, he saw them as a graphic example of a deeply and damagingly counterproductive way of organising our lives. (Another of his books from the 1970s, Medical Nemesis, goes further in analysing the same patterns of industrial counterproductivity, as seen in our systems of healthcare; but his original plan, on this occasion, had been to use as his example the U.S. Postal Service.)

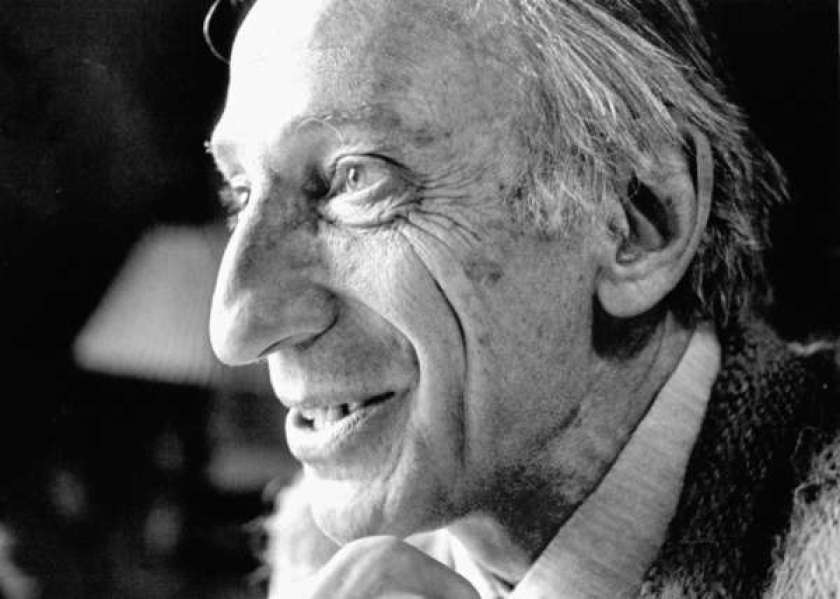

Illich had no desire to tell people what they wanted to hear. “He could be so rude!” his friend Barbara Duden told me. She recalls him exploding at a questioner, “You’re too stupid, I cannot talk to you!” Probably it would not bother him, then, that his work is read by many as offering critique without hope of an alternative. Yet this perception is not true to my experience of his writings, nor of the surviving community of his friends. From John McKnight’s Asset-Based Community Development to Gustavo Esteva advising the Zapatistas, the members of the Illich Conspiracy – as I like to think of them – have hardly retreated from the world in despair. Their work is evidence of the hope to be found in his writings; but finding it may be closer to the experience of getting a joke than of signing up to a manifesto. There are no blueprints for building a better world here; only clues to how we might act, given the kind of world in which we find ourselves.

The desire to offer a more positive spin on Illich’s message would scarcely justify the cheek of this retitling with which I am playing; but Rehoming Society works for another reason: it points to the continuity between those critiques of industrial society which brought Illich to international attention and the themes of his later writings. For a while, in the 1970s, Illich enjoyed – or endured – a level of intellectual celebrity comparable to that of Slavoj Žižek today, but in a time when the neoliberal mantra of “There Is No Alternative” had yet to entrench itself. Even the Encyclopaedia Britannica opened the 1970 edition of its Great Ideas Todayseries with a symposium on “The Idea of Revolution”, including contributions from Illich, the historian Arnold Toynbee and the anarchist thinker Paul Goodman.

By the end of that decade, the world had taken a different direction, and Illich’s profile waned. The writings which followed feel, to me, like the work of a man who has been relieved from the bother of fame and finds himself free to pursue, in the company of friends, what matters most to him; though there is also a sadness at the path the world had not taken. Together, they form a deeper historical enquiry into the buried assumptions underlying industrial society. They have had far fewer readers than Deschooling Society(1971) or Tools for Conviviality (1973), but they are gradually being rediscovered, for the converging economic and ecological crises of the new century only sharpen their relevance.

When people ask me where to start with Illich, I hesitate. His writing is not obscure – it is powered by the desire to be understood, rather than the desire to dazzle – and yet it is not easy, either. As Ran Prieur puts it, “Illich was so smart, and wrote so clearly, that I can barely stand to read him – it’s like staring at the sun.” If there’s one of the later books that will really take you into the heart of his thinking, though, it is Shadow Work(1981) – the collection in which he introduces the concept of “the vernacular”. Starting from the history of language, he broadens this term out to encompass its fuller Latin meaning of all things home-made, home-spun, home-brewed. The vernacular, in Illich’s usage, names the mode of life (in all its plurality) which was overshadowed by the rise of industrialism, in which the dominant form of production was within the household or the local community, while commodities traded for money formed an exceptional class of goods. As industrial society destroys itself, the remnants of the vernacular emerge from the shadows, not as some prospect of a return to an earlier and simpler way of life, but as clues to how we may continue to make life work and make it worth living.

If such a historical argument seems removed from the business of our day-to-day lives, the experience of the vernacular is not so far from reach: Think of the difference between a shop-bought birthday card and one made by a friend, or between the experience of cooking for people you know and care about, and that of working in a restaurant kitchen. None of this is to say that exploitation and domination cannot exist within the vernacular domain; but it is to suggest that there are possibilities for meaning and joy within it that are far rarer within the production of commodities for strangers.

And, at this point, we are back to Bridget’s challenge to the assumption that life is a journey outwards, through school, into the world of work. In her essay and in the direction of Illich’s thinking I find the suggestion of another orientation: that we might choose, instead, to find our way home, wherever that turns out to be.

The conversation which follows took place in the garden of a cafe in The Hague in June 2011. I had spent two weeks hanging out with a gang of Illich’s surviving friends and co-conspirators, first in a small town in Tuscany, then on the edges of an academic conference on the marketisation of nature. On our last morning, I wanted to make a record of a little of the thinking that had gone on during our time together.

Sajay Samuel trained as an accountant in India before arriving at Penn State University in his late 20s. There, he found himself invited into the household that formed around Illich and, over the next ten years, he travelled and studied as part of that group. We first met in Cuernavaca in 2007, at a gathering to mark the fifth anniversary of Illich’s death: I arrived knowing no one, and immediately found myself encircled with friends. Since then, I have found in Sajay’s work a kind of intellectual trellis on which my winding thoughts have been able to climb. It has had a powerful influence on my thinking and fed into the background of Dark Mountain. Too little of that work has yet been published, so – as I told him when we sat down to this conversation, hoping that the presence of a recording device would not inhibit its flow too greatly – it is a pleasure to be able to contribute to making his thinking more widely available.

SS: Thanks for the opportunity. It’s perfectly true that not much of my stuff is out there, and hopefully conversations such as this will serve as vehicles to find people such as yourself to think in common with.

I’ve devoted perhaps the last seven or eight years of my thinking to follow the threads put in place by Illich and see whether or not I can elaborate on them to enable my own understanding; which is different to saying I need to elaborate on them to make his work better – that’s not the mood or the stance in which I approach his work. Of course, it’s built on the conviction that the corpus of his writings represent a stumbling block for most of contemporary thinking– and that, if you don’t engage with it, you miss out on a significant, new and enduring way of thinking about the contemporary situation. And therefore engagement with Illich is not only personal for me, but also because I think it illuminates our condition.

Perhaps the best way to enter this line of reflection is to start with what most of us now take for granted and as obvious: the economic crisis and the ecological crisis. Curiously and unsurprisingly, Illich had suggested the shape of both of these a generation ago, which points to the fecundity of his thought and the errors of ignoring the warnings of that kind of… prophetic seeing, if you want.

DH: Indeed, and I would just add that what that prophetic seeing involves is seeing what is already obvious, but is unspeakable to those who have something to lose. It’s not a supernatural divination of the future, it’s not futures “scenario mapping”. It’s speaking the truth about that which is already manifesting in the world, but which many people can get away with still pretending is not there. That’s the spirit in which I see Illich anticipating so much of the mess that we’re in.

SS: Right, so a clear-eyed view of the present – and I perfectly agree with you, there’s nothing of the tones of mysticism and New Ageism. For me, it’s an extraordinarily tightly thought through set of arguments that start from intuition, but then are shown by argument and reveal the present in a very new light.

DH: So among Illich’s concepts and thinking, what do you think is most useful to the present moment?

SS: Well, this also touches upon something I’ve learned from you, in the last couple of months. I think the key concept is “the vernacular”– and I’m encouraged and emboldened by your way of thinking about, or not thinking about, “the future”– the sense of the tension between the Promethean stance versus an Epimethean stance. So, the vernacular for me is now increasingly occupying the position of the pivot in an argument that I think, if one does not engage with, we miss a moment and might continue in our blindness to exacerbate the Promethean temper. We risk flying away from being tethered to the earth in any sense.

DH: And so how do we define “the vernacular”?

SS: This is a question that becomes important to Illich around the eighties, at the end of his reflections on industrial society expressed in, for instance, Deschooling Society, Disabling Professions and Medical Nemesis. He is attempting to write a postscript, he says, to the industrial age. And in doing that, he is prompted to ask: what did the industrial age destroy? What were the historical conditions that persisted and prevailed, upon which the industrial mode of society built by destruction?

DH: And there is a sense that, in witnessing the end of an age, one is able to notice more clearly than one’s immediate predecessors the things that were lost in the beginning of that age – I think that’s a returning pattern in Illich’s later work. So you’re saying that the vernacular emerges as a description of what was lost and destroyed in the foundation of an industrial age which he is witnessing the beginning of the end of?

SS: And therefore, for him – or so I argue – the deliberate use of the vernacular as a term – instead of, for instance, “subsistence”, which would be Polanyi’s term, or “primitive accumulation” in Marx, and so on – is precisely to broaden the frame within which we think of that which was destroyed. In the fading moments of the industrial age, something comes into view: that which the industrial age destroyed. But it comes into view in its fullness, not in the mirror of the industrial age, which is confined to a kind of economic understanding…

DH: And this word “vernacular” means home-made, home-brewed, home-spun. It’s got a richer sense than simply “production for use value”, but it refers to some of the same things that, from a Marxian perspective, might be referred to through that lens.

SS: So, for instance, we can predicate of the vernacular, “vernacular architecture”– we can’t speak of “subsistence architecture”– we can think of “vernacular dance”, “vernacular music” and so on, to indicate forms of life that are characterised as based on the household. So it expands the view of the past beyond the lens of the economic.

And this then will become the pivotal thinking block about what happens today, in the light of the economic crisis, in the light of the ecological crisis. I’m convinced that we’re thinking about these crises in two ways, both of which are limiting. In the case of the economic, we think of the choice available to be between a “managed” capitalism and a free market. With the ecological, we think the choice is between industrial machinery and a Prius car, eco-friendly technologies. But in both cases something goes unexamined– in the case of the economic, the realm of exchange value is not problematised: it’s a question of how best to arrange those exchanges – and in the case of the ecological, the realm of technology is not problematised: it’s a question of its intensity vis à vis the environment.

DH: And so, in the argument you’re making, the attention is drawn to the hidden consensus between the poles around which an area is generally framed. It’s still very common to speak as if the space of politics is mapped out by the state at one end and the market at the other end, and what we’re doing is sliding a rule somewhere between the two. And in terms of how we respond to ecological crisis, to look at how far down we can slide from the dirty tech into the clean tech. And in both cases, this is a way of framing things which misses out – and makes it almost impossible to see, from the perspective which these frames create – a whole world of people’s lived experience and how people have made life work, and continue to do so.

SS: I love that image of the sliding scale: you have these two poles, and you have a little meter that slides more or less. And it absorbs a great deal of the contemporary conversation, this frame. So the Illichian argument, as I’ve understood it, is – let us first historicise this frame and ask, what is it predicated on? What does it lead to? What kind of ways of living does it lead to? And what does it mean to inhabit a way of life that is outsideof these frames?

So, in the case of the economic, if the sliding scale that unites these two poles – market and state, market and regulation – is in fact the commodity, then the question is to problematise the commodity. To ask, can we not think of the commodity as putting into the shadow, putting into abeyance, something else – the non-commodity? And ask what is the balance between these two that leads to a more enriching kind of life, a life that is not disabled by dependence on things that you have to buy, which means you need cash, which means you have to be inserted in the economy and subject to jobs and production and consumption.

DH: The question that immediately begins to arise, as we try to talk about this – and, in some ways, is used to police the boundaries and keep the conversation within these sliding scales – the question is, aren’t you being romantic? We know the argument: life in the past was actually a Hobbesian nightmare; people’s lives were shorter and more miserable, and yes, we might have traded a new dependence on money in modern industrial societies for massively increased material production, but it was a trade worth making. Polanyi is a dirty word to a lot of people because they hear what he is saying as a romantic, declensionist narrative about a Golden Age of the past. So how do we speak about the vernacular, in the way that we are beginning to do here, without immediately being heard as and shut off by that response?

SS: So, the more trivial response to that kind of reaction – you’re being romantic, you’re telling us a story of the Fall – is to say, “Who speaks?” Arguably, one would say, today, of the benefits of industrial society – of which you and I are beneficiaries, to some degree – that such a statement does not hold for the vast majority, who are in fact driven from relatively low levels of cash dependence into total cash dependence.

It is only through an economic lens that the peasant is understood as poor. I grew up in a time when my grandfather still wore no shirt and had a towel thrown over his head and we used to draw water from a well. For a man such as he, there was no need of a shirt. Now, to say that a shirt improved his life, on the condition that he got a job so that he could pay for a shirt, is a curiously perverse kind of view.

So yes, who speaks – and for whom do they speak? Arguably, the beneficiaries of this industrial way of life are a few, which necessarily entail that the many be uprooted, removed from vernacular ways of living that are low levels of dependence on the commodity, and be thrust into the commodity economy, which I would call being introduced to a life of destitution.

DH: And one of the clues that has come increasingly into focus for me is to see how clearly the winners of what Illich called ‘the war against subsistence’ proceed to reenact the vernacular, under conditions of scarcity. So that those who can afford a five-dollar artisanal loaf get to eat what was once everyone’s bread. Unravelling that – unpicking the consistency with which those who do best out of industrial society restage, as commodified and pay-to-access worlds, things which look a hell of a lot like what we are describing when we talk about the vernacular – is itself a clue to what we’re trying to bring into view here.

SS: So the rich man today is the one who can avoid the traffic jam, imposing the jam on everyone else! Curiously, the industrial society and the industrial system is now denigrated by those who benefit from it the most. And, as you correctly point out, and this is really worth looking into, the vernacular is brought back in a counterfeit form – in an intensely commodified form…

DH: Or in a complex, muddled form – when I was talking about this with someone here yesterday, they said, “Among my friends, who are of a generation who don’t have a chance of buying a house because of what has happened in the property market, there is a willingness to spend more on really good food from the farmer’s market.” So there’s a complexity to this – I don’t want to say that the survival of things which have a flavour of the vernacular in these privileged zones is totally counterfeit. Even this can contain a line of transmission which, as the industrial age unravels, might play its part in the reemergence of the vernacular.

SS: Fair enough! But to go back to the challenge – you’re being romantic! You want to bring back forms of life that were nasty, brutish and short! – the second response is, I think, what the contemporary moment shows, and has been showing for a generation – the utter impossibility of the industrial, commodified exchange system to produce the kind of jobs that it promises. The default condition for the vast majority of people today is to figure out ways to inhabit the interstices of a collapsing market system – and unless and until as many of us figure out how to do this in an open, joyful, constructive way, we get mired in a kind of helplessness, a kind of self-destructive, other-destructive hatefulness. To experience destitution and not have a way out, either in thought or in practice, seems to me to compound misery with evil, to leave people – to leave myself! – in a place of hopelessness.

DH: This reminds me of a conversation I had with the photographer Sara Haq, who was talking about her father. He came to England from Pakistan over thirty years ago and has worked as an accountant. The one change that he has seen in the time that he has been here, he says, is that back then it was possible to support a family on an ordinary salary, and now it is not. He sees England heading into the problems that poor countries have, without the things which allow people to get by and make life work where he came from.

So what we are talking about is the return of the vernacular: the rebirth, the reemergence of the things which made life liveable in the past. Because, in a sense, Illich’s historical enquiry starts with the question: why is it that these people in the past, who according to our lights ought to be thoroughly miserable, don’t seem to have been?

SS: Exactly! I never forget the impression that “Stone Age Economics” made on me. Marshall Sahlins, the anthropologist, points out that the Aborigines of Australia spend vastly more time in leisure, in playing around – they are not this image of nasty, brutish and short, by any means. And so, you know, the second vector of responding to this somewhat dismissive charge of romanticism is to highlight the fact that the promise of industrial society, the promise of market society, is undeliverable. It just can’t deliver to the vast majority. And therefore, to continue to inhabit a thought-space which excludes thinking about the vernacular is to make impossible an escape from that which condemns you to destitution.

This is the line of reflection where I think Illich has something very profound to say: look here, the vernacular was destroyed, but not destroyed completely, there are always rests and remnants. People continue to reinvent, to invent in creative modern ways, increasingly unplugging themselves from the market or dependence on the commodity. And unless thought aligns with that mode of existence, unless we rethink the vernacular in modern ways, in contemporary ways, I think we reach an impasse of the mind where not much more can be said. The industrial system has failed: within that industrial mindset, no new ideas are possible, nothing new is possible, and we lurch between free market and state, free market and state, continually.

DH: So does the vernacular have a hope, in the age of management? Jennifer Lee Johnson was talking here yesterday about her work around Lake Victoria, or Nyanza, where vernacular fishing-to-meet-one’s-own-needs is criminalised because it doesn’t fit the fisheries management policies. Is management in the broader sense, managerial politics, systems administration – is that a totalitarian thing against which the vernacular doesn’t have a chance of emerging, or does the vernacular have a fighting chance?

SS: Right, so this has impelled a line of reflection: can we characterise in some way the nature of ideas and practices that emerge from and support the systems administrator? And it seems to me that here one can do a certain amount of history of the ways of scientific thought, for instance, or of managerial thought– and the first thing to observe is that the manager speaks from nowhere. Arendt has this beautiful image, in attempting to describe scientific thought at the moment when the first moon landing happened, she says: modern science is predicated on viewing the earth from very far away, from the point of view of the moon, a kind of lunar– with all its resonances– a lunatic view of the earth. The first thing to note about the systems administrator, he does not inhabit the space or the place that people inhabit. Forms of knowledge that grow out of practices that are embodied and in place are foreign to and antithetical to the ways and styles of thinking that managers and systems administrators presuppose.

So you ask, is there a fighting chance for the vernacular to come back in a world of systems administration? One way to get at this is to ask, is there a systematic difference in the nature and the kind of ideas and practices systems administrators deploy, versus that which grows out of embodied practices in place? As a first pass – and one can elaborate the steps of an argument – but as a first pass, the lunatic view of the earth is sufficient to get at it. So you ask, under what circumstances can the vernacular reemerge legitimately within the system administrator world, and it seems to me this fight has to be fought on the plane of legitimacy first. One has to make illegitimate and improper certain ways of knowing and seeing and doing, without which what people are attempting to do on the ground can fall prey to this charge of romanticism– Ludditism, cussed, backward– these words are clubs that stand in the frontline of the fight, the fight between two ways of seeing the world, seeing oneself, seeing what one does. Unless one takes that fight to the right plane, it seems to me, we hobble ourselves.

DH: So how do we do that?

SS: What I’m attempting to do is to work out an argument which suggests or shows that the system administrator’s view of the world presupposes, as a necessity, the absence of persons. The system administrator must necessarily look at persons as objects, as variables, not as embodied beings – not as father, mother, sister, brother – not as fleshy people with hopes and desires, but abstract models of people. Statistical representations and medical systems, economic models, homo economicusin economic policy and planning – so you get these strange, one-sided, reductive, desiccated views of people that populate scientific models that are then used as armature, the weapons in a policy programme, and then of course become realised. And what this way of seeing does is to destroy the condition for people to inhabit their own livelihood.

So the way to counter this is to make that illegitimate…

DH: …to bring into focus the extent to which that is a way of seeing, rather than part of background reality – and to question its foundations, the assumptions with which it begins, and what we become, in our own description of ourselves, once we’re talking about ourselves as components within a system…

SS: Let me give a concrete example: I’m in the university system, and one of the enduring vehicles by which the teacher and the student come into relationship is the reward and punishment grade. And this goes back seventy, eighty years – work hard, you get a little grade; don’t work hard, we punish you with a grade – and now that relationship is reciprocally cemented: teacher does well and the student evaluation is good, else it’s not. This relationship modulated by rewards and punishment is based on a Skinnerian view of people, a view of people that Skinner gets from thinking about rats and pigeons.[6] The more we engage in this kind of technology of behaviour modification and control, the more students and teachers play to that description of themselves. Today there is a great hue and cry: “What has happened to the students’ curiosity to learn? Why do they do only that which is demanded for grades?” Well, surprise! For seventy years we’ve been using this reward system, and now they behave like Skinnerian monkeys or pigeons – and everybody’s shocked? The deployment of a particular view, model or seeing of people then gets realised within particular institutional settings, and the question facing us is to delegitimise those ways of seeing people.

So what is the work that I’m attempting to do? It’s to clear the space, if you want, in these small forays of war against– let’s say, scientific ways of thinking, for instance, or the systems view of man, or the war against the vernacular– open up different fronts, to clear the space for something different, which is already there– it’s not an act of heroism– these little wars, these battles are as much to clear my own mind. The act of working through something, thinking through something, with you, with friends, writing about it, clears up in one’s own mind the space that needs to be cleared.

DH: One of the things that I’ve valued about your work is the – I don’t know if this is quite the right description, but the search for a qualitative rationality. Because the dominant mode of rationality for many generations in the west has been quantitative – and you can say more about the history of that. But the gut reaction, the intuitive reaction against that reduction of reality to things that can be measured and counted is very strong, and the risk has been – and in some ways, this is where the charge of romanticism manages to get a purchase on us, or our friends – that the qualitative reaction against quantitative rationality often celebrates the irrational. Whereas what you’re doing is an out-reasoning of Cartesian rationality.

SS: I’m glad you brought me to think through again with you this particular issue. Because you’re perfectly right that the fault-line, if you want, in contemporary discourse is drawn along rationality/irrationality. Say something about the systems administrator and his or her view of the world, and they say you’re courting irrationality. Say something critical about scientific ways of understanding the world, you’re courting irrationality. And so my interest has been to get out of that game, to ask– who framed this game the way it is framed today?– just as we’ve asked regarding economy or ecology.

And there I find, with the help of masters, a curious moment in seventeenth century Europe, for which we can take Descartes as an example. They’re inheritors of a theological question coming out of the high Middle Ages, as best I can understand it: how and why does God know everything? Answer: God knows everything because he made everything. Ah, so God’s knowledge is complete and he’s omniscient because He’s made everything, so “making” and “knowing” are an identity!

Descartes asks the following question (I paraphrase): Is the geometric form of a perfect circle given to us in nature? No. So how did it come about? Answer: We must have made it up. Now notice that what he’s reacting to, or what he’s fighting against, is a long tradition – one might say, as shorthand, the Aristotelian tradition – of how “understanding” happens. For Aristotle, very quickly, man’s “concepts” – which, etymologically has a resonance with grasping and touching – man’s concepts are tethered to the senses, the sensual understanding of the world…

DH: So knowledge begins with perception?

SS: With perception. This is not the same class as what Hume and Locke, the empiricists, will call sensation, it’s of a different kind because for Aristotle, for example, that chair there, that object emanates, emits its form to you. It’s not as if it is undifferentiated sensation…

DH: …it’s not the sensation that ripples off from a mathematical reality; the chair is a presence which is speaking to you, and your gaze goes out to the chair – so perception begins with an encounter.

SS: Right, and so coming back to Descartes, he says, look here, about these geometrical things, the perfect circle, who cooked that up? We did. Ah, so the imagination must be creative, in the strong sense – in the sense of creation ex nihilo, something from nothing. We know there is a perfect circle because we made it through our imagination. And thus you immediately get the context in which this claim comes around; we want to be masters and possessors of nature. And the way we do that is by realising the identity between knowing and making. We can makesociety, knowing and making, in Hobbes. We can make property, knowing and making, in Locke. And so this general idea that knowing is identical to making, exemplified by mathematical objects, forms the pivot on which the modern move turns. And for me, then, that constitutes the frame, you see: The reason why we privilege mathematics so much is, in part, because it discloses the knowing/making connection, and that’s the thing we don’t want to give up.

In this fight between qualitative and quantitative, the next move Descartes makes is to insist that any object can be reduced to a set of characteristics that can be quantified.

DH: A set of variables, a statistical representation.

SS: So the thing itself disappears and it can be re-presented as a set of variables in mathematical symbols – and we’re the inheritors of this move. We have to understand that this move is done in the context of mimicking, if you want, the all-knowing God. And what disappears from view is the world of the given, and so, for me, the qualitative/quantitative argument is an attempt to resuscitate, to go behind this original framing that privileges the quantitative: for what reason do we do it? Why do we privilege the quantitative? For a certain reason. At what price does it come? The extinguishing of quality.

And I find a very potent argument in Plato, for instance, where he says, look here – I adapt this – the distinction, quality and quantity, need not be that between irrationality, emotion, etc, and rationality, thought and so on. Rather there are two kindsof quantities – numerical, which we can call arithmetic, and then, “too much”and “too little”. By definition, “too much” and “too little” are quantities, but they’re not numerically measurable. What we have done in the modern world is to privilege 1, 2, 3… as the only kind of quantity. But I can relativise, I can put under epistemic brackets, that kind of quantity by insisting on the superiority– and showing the superiority– of the second kind of qualitative understanding, “too much” and “too little”. For example, we can ask: have you gone too far, by measuring love in terms of numbers? A perfectly legitimate, perfectly logical, perfectly sensible statement. Number cannot provide an answer to the question of “too far”. The measure of going too far by measuring love in terms of numbers is six… Totally insane!

So, you say I want to out-argue the fixation with the quantitative in the modern – yes, but on quantitative grounds. I’m counter-arguing it, not on privileging the emotions, not on privileging sentiment – which are, by the way, staged “others” to the privileging of number – but rather on quantitative grounds, though not numerical. Insisting on the importance of “too much” and “too little” as the matrix within which number can be thought through. Have we gone too far, mathematising the world? Do we have too much of mathematics around? It’s a question of using judgment regarding “too much” and “too little”.

And I think that comes back into the question of common sense – a commonsense understanding of the world, which is then rooted in the sensual and therefore rooted, more or less, in vernacular modes of being. So, some have accused me of an overly structured kind of argument – but for me, that would be the line of thinking. The vernacular was destroyed by a certain style of thinking, and therefore a certain way of being – call it “commodity-intensive”, call it “disabling technologies” – all superintended by a kind of mathematical understanding of the world that is untenable. The question is, how to make the vernacular legitimate again? You can fight on multiple fronts. For me, having trained as an accountant, number and that zone – my thinking has been devoted to unpacking that.

DH: And I think it’s a very powerful – partly because an unexpected – place to take the fight.

SS: Right!

DH: There are so many further places we could go from here, but what fascinates me about this conversation and many others that have been going on around Dark Mountain is the intimate entanglement between very long historical views and deep cultural questioning of ways of seeing, ways of knowing the world which have been background assumptions for centuries, with the urgent sense of living in a moment where a lot of things are in flux. Maybe we could finish with – I don’t know if, even, ‘what happens next?’ is the right question – but, where do we go..?

SS: I was very impressed by your way of thinking about where we go from here – the metaphor of return is not such a bad place to go, comprehended in its fullness. So, we had a brief discussion some time ago, and I told you of reading this essay where the man says, “When you’re at the edge of a cliff, you can fall off, and the sensible thing to do is to turn back.” That’s a kind of turning back, but as you pointed out, one doesn’t get a feel for return…

DH: …because a cliff is something that can be drawn with a straight line… To me, the return is – it has an element of the uncanny, because at the moment in a story where you bring back something from earlier on, everyone, including the storyteller and the audience, experiences this deep satisfaction. And that is because you have performed something which brings the cyclical and the linear experiences of time into rhythm, into timeliness. And… I haven’t theorised this properly, but there is something about that which is very deeply connected to meaning, as we experience it. It’s not the same thing as a desire to rewind – which is what is perceived as the romantic thing – you want to rewind to 1641, or wherever. It’s not that, it’s recognising the moment when something from further back in the story weaves in and provides the next move, as you’re stumbling into the unknown.

SS: That’s exactly right. The present reveals, exposes itself in a way that the past, sort of, bubbles up again. Do we have the patience, the stillness to recognise that? And through it, something else forms. I think that’s the answer to where we go from here. And in a funny way, my intellectual labours are directed to clearing the space so that we can recognise the past as it bubbles up.

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 3.