There were eagles riding the air overhead as we took the backroad out of San Pablo Etla to the Casa Esteva. The taxi driver had left us at the crossroads: at ease in the highspeed free-for-all of the highway, he had no desire to risk his exhaust on the unpaved road ahead, so a young man from one of the neighbouring households drove down to collect us. It was three months into the dry season. We bumped across the bed of an empty stream before climbing again towards the adobe house among the trees.

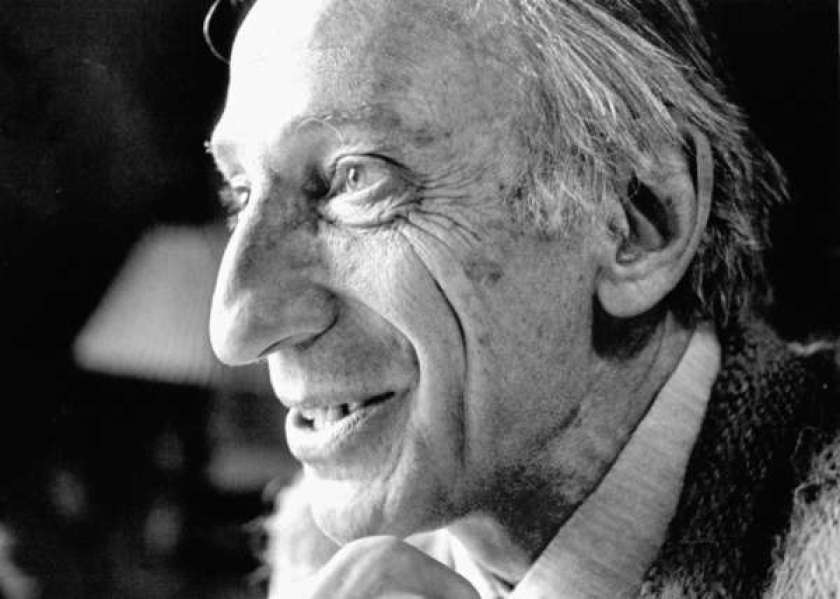

After days in downtown Oaxaca, its streets clogged with fumes, the air up here was a release. Twenty-five years earlier, when Gustavo Esteva and his partner left Mexico City to settle here, they must have felt that same contrast. For Gustavo, it was a return to his grandmother’s village: the grandmother who, in his childhood, was not allowed to enter his parents’ house by the front door, nor to speak to her grandson in Zapotec.

‘For my mother,’ he told me, ‘the best thing that she could do for her children was to uproot us from any connection with our indigenous ancestry, to avoid the discrimination she had suffered.’

Despite this, the summers he spent with his grandmother on her stall in the market in Oaxaca planted stories that would come to life much later.

Meanwhile, as a young man, he took refuge from the cultural confusions of his family in the promise of ‘development’. The term which would frame the relation between the countries of the post-war world, embodying a unifying model of global economic progress on which even Cold War opponents could agree, was first used in its modern sense by President Truman in his inaugural address of 1949. At 15, following his father’s death, Gustavo found work with the first wave of global corporations bringing the reality of development to Mexico. Before too many years had passed, he would become the youngest ever executive for IBM; but instead of taking his place at the centre of this grand narrative of economic progress, he found himself standing on one side, the side of the bosses, being asked to cheat the workers.

So, in his early 20s, he walked away from that career and before too many years had passed, he had become a Marxist guerrilla. This was the era of Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution: if capitalism could not deliver the promise of economic progress for everyone, it was time to fight for the alternative. Marx would remain a deep influence on his thinking, but this phase of his life ended, again, in disillusionment: he parted with the idea of violent revolution after one of the leaders of his group shot the other in a row over a woman. ‘It was a revelation of the kind of violence we were imposing on ourselves and we wanted to impose on the whole of society.’

For a second time, he walked away from what had looked like a means of making a better world. In the years that followed, he continued to read, study and write about economics and social change, and before too many years had passed, he had become a senior official in a government agency. By the early 1970s, he was running programmes to control the market in basic staples, providing food security to millions of the urban and rural poor. Yet this phase, too, would end in a decision to walk away, one that would shape the rest of his life.

In 1976, due to the success of these programmes, he was in line for a ministerial post in the new administration. ‘By that time, I knew at least two things: first, this is not what the people want, these beautiful development programmes. I did not know exactly why or what it is that the people want, but I knew that it was not this. The second was, the logic of government and the logic of the people are completely different. Even this populist president – I was in the presidential house, many times, in cabinet meetings – how they take decisions and what the people need and want are two different planets.’

I knew the outline of this story, but as we talked on the porch of the house that they had built, what struck me was his willingness to trust in his own uncertainty. At each of the turns in his journey, he had been willing to renounce the security of existing structures, structures he had come to find intolerable, even though he had no answer as to what else could be done. Willing to go and wait in the wilderness, with patience, to see what new things might come into view as a result of that letting go.

Having walked away from the prospect of high office, he went to work at the grassroots, in the villages and on the urban margins, with peasants newly arrived in the city. He talks about this as a time of happiness and confusion: among those with whom he was now working, those who were supposed to be the underdeveloped, he found what seemed to him a good life. Yet none of this made sense within the frameworks of economics, anthropology, sociology or political science. It was as if he had to choose between the whole theoretical frame of development which had shaped his life and the evidence of the lives of those around him. This was pushing him to a crisis.

‘Suddenly I said, one day: I will take off the glasses, the lenses I am using, all the different lenses of development. To abandon those categories, it was like the moment when you come from the darkness into the light, and you are just seeing shadows.’

Two things, he said, helped him to make sense of his experience. The first were the memories of his grandmother that began to surface again, the stories that she had told him in those childhood summers. Lessons which he had not understood at the time now took on meaning. It was this, he says, that made it possible to connect with the people around him.

The second was his encounter with Ivan Illich. On the Marxist Left in the early ’70s, in the years of his most famous work, he had been no more than a reactionary priest, not worth reading. His critiques of schooling and health systems were beside the point: of course, in a capitalist system, these things would be bad, but after the revolution we will have good schools!

When they met in 1983, what struck Gustavo was that the terms of Illich’s thinking made sense in the light of the lives of the peasants and migrants with whom he was working. I had heard this before, but it was brought home to me later that month at a conference in Cuernavaca: after two days of dispiriting academic presentations, the one talk in which Illich’s ideas actually came to life was given by a woman from an indigenous community who had only come across his books a few months earlier.

It was in Cuernavaca, five years earlier, at a gathering to mark the fifth anniversary of Illich’s death, that I had first met Gustavo. Then, the following year, he came to London and I saw him polarise a room full of social entrepreneurs and young NGO workers with his stories about the paradoxes of development. Somewhere around that time, I began to meet up with a guy called Paul Kingsnorth who had an idea for a journal called Dark Mountain, and it turned out that the one person we knew in common was this old Mexican who called himself a ‘deprofessionalised intellectual’. Paul had interviewed him in Oaxaca, when he was writing about the Zapatistas, and it was Gustavo who gave him the title of his first book, One No, Many Yeses.

That is not the only way in which Gustavo’s thinking is entangled with the roots of Dark Mountain. The life out of which that thinking has grown is a story of faith in progress, the loss of that faith, and the finding of the kinds of hope which remain on the other side of loss. Then there is the willingness to walk away, even though you have no answers to give when people ask what you would do instead, to walk away with only your uncertainty, rather than to stay with certainties in which you no longer believe. Finally, the distinction he makes between ‘the better life’ promised by universal visions of progress and development, and ‘the good life’, which has to be worked out on a human scale, improvised, in the times and places where we find ourselves.

The conversation reproduced here was recorded by Nick Stewart as part of a film on which we are collaborating. His is the unspoken presence in what follows: not only because he was moving about with a handheld camera, finding the angles from which to catch our expressions as we talked, but because he then produced the initial transcript on which this text is based.

DH: It seems to me that ‘development’ begins by talking as if one country is a poor version of another and ends by making that the case: you end up with poor copies of things that were developed in other times and places. It’s not to say that ‘living well’, as you put it, involves a hermetic sealing, keeping out the new. It’s that, if one is starting from the idea that this is something we have to work out here and now, rather than something that is worked out by others on our behalf, that will lead to a kind of questioning of new technologies and new ideas. A dialogue with them, rather than an unquestioning acceptance or demand for them.

GE: There are two things that I am involved with in your observation.

One is, we are now forced to put limits to our hospitality, because of hospitality abuses. The people here in this area of the world are very, very hospitable. They open their minds and their hearts and their arms to everything. But then, the occupation of Mexico by the Spaniards started with an abuse of hospitality. Montezuma was hosting Cortez as a great guest and then Cortez took him hostage in his own palace. Well, this kind of hospitality abuse we can see for the last 500 years. All the time, we open our minds and our hearts and our arms, and then something horrible happens. And this can be a person, a country, invading us. Or it can be the Green Revolution, or whatever kind of technology. Then what we are saying, now? It’s not closing ourselves, no, but let’s be careful. We cannot be so hospitable to anything that comes. We need to first examine what is coming and then define if we want it or not. That is being careful, particularly about these technologies.

But there is another point in your observation: for many years we accepted that something like poverty or underdevelopment was objective. We were underdeveloped. There were ‘the poor’, as something very clear. And then, after years, we discovered that poverty is just a comparison. ‘These people are poor because they don’t have what we have!’ Because they lack the family car or the college degree, or the beautiful house, or a certain kind of shoes, or iPod, or whatever…

DH: All of which become the markers on this scale of ‘the better life’, as you tick off one after another, reaching upwards, hoping that somewhere up there it’s going to get less lonely than it seems to have become along the way.

GE: But if you are seeing the people by what they don’t have, then you are not seeing them.

That is the problem with ‘poverty’. Who are really the poor? One thing the anthropologists are all the time asking themselves is: why are the people in these very poor villages laughing so much, celebrating life so much? They should be very sad, because they are so poor. They are not so sad. Let’s try to see them for what they are, who they are. Not just comparing them: oh, they don’t have this or have that.

DH: I think this is where some of the fear comes from now in what I have come to think of as the ‘undeveloping countries’ of the postindustrial West. There’s an assumption, which comes from this scale of development, that what we have had in Britain or America is the better life. Given that, for many people, it’s actually quite a disorienting, stressful life, imagine how much worse it must be once you go further down that scale! We must at all costs prevent any kind of falling down, even if it means we have to sacrifice more and more of the things that we used to think were part of the deal for us. So the deal keeps getting worse, but we have to keep working the longer hours and retiring later, and so on, because the alternative is to fall into this hell of poverty which is projected onto the lives of most of the people on the planet.

Part of what I’ve been wondering about, as I think about this phenomenon of undevelopment, is how people find the clues that it might not work out like that. That, in the process of losing many of the things that people like me grew up taking for granted, we might catch some of the threads that we dropped further back in time, find new ways of picking them up. Becoming part of the world again.

GE: Some friends of mine from Italy and Spain have been telling me with great concern that now the people on the streets are very, very conservative. They are there to conserve what they still have. And it’s a legitimate concern, of course: they had jobs yesterday, then they want the job back. But this implies that there is something worse than being exploited: not being exploited. I want my chains back! I want to be exploited again! We cannot see that way, we are seeing only the loss.

I would say the most important point for me, in this kind of conversation is, first, let’s be brave enough to see the horror in which we are today. It’s a real horror. We must not qualify it, it is a horror. We are destroying everything. The idea of trying to keep, only to keep, what we have today in the world: this is to continue the destruction on a bigger scale. And because we are in that condition, and because the people are reacting to that condition, the powers-that-be are reacting in a horrible way. And that means you are seeing a lot of violence, a lot of control of the population and many terrible things.

So first, we need to be aware of the horror, and not just falling into a kind of apocalyptic randiness and saying, December 21st will be the end of the world. It is really discovering in our own societies, in our own beings, every one of us, the elements of that horror.

And then, in that same observation, discovering the absolute irrationality of our desires: how we define our wants, what kind of definitions of the good things we have. If we begin the reflection of ‘What is it that I really want?’ Not what the market is telling me to want, not what the state is telling me. What is it that I really want? Then we start saying, ‘Oh, I want love!’ I want a very close relation with someone, I want to laugh all the time or I want to cry all the time…

DH: ‘I want to not be constantly feeling precarious.’ I think that’s one of the deep desires in the undeveloping countries: the sense of precarity that affects most of the population, now.

GE: This is a very important point. I know that this word is now used more than ever. Precarity. And the immediate reaction, a conditioned reflex, is: the institutions can offer me protection from precarity.

DH: Yes. There’s a kind of yearning for a return of the social democratic golden age. I sometimes talk about the fantasy of the social democratic End of History, which afflicts many people on the left in Europe. That, if it wasn’t for these neoliberals coming along, then we could have had social democracy for everyone, forever. And it’s as historically illiterate as the Fukuyama ‘End of History’ fantasy. It’s the same thing, albeit in a kinder form. So, yes: what’s the alternative? Rather than imagining that we can rebuild the social democratic institutional support that kept people for a while from a sense of precarity in the West, where else do we look?

GE: We have reached the point in which the institutions, in every country, cannot offer us any sense of stability and the elimination of precarity. It is, I think, a fact that no country will be able to pay the bills of education and health and pensions. It is useless to continue the discussion about that kind of thing. Of course, we need some institutions, and, of course, we need some operation of these institutions to keep the society going. I’m not saying dismantle all the institutions tomorrow morning and that’s it.

But if you want to abandon that feeling of precarity, then it’s to rediscover that the only way to have a kind of security is at the grassroots. With your friends. With the kinds of new commons emerging everywhere. Then, together, the people themselves, with their neighbours, we can create the kind of social fabric that can really offer us security, protection and a good life. The possibility of living well.

DH: For that to work, there has to be a rediscovery of a ‘self’ which is not the self that economics has taught us we have. Part of what I see is that the nightmares that are haunting the West now are nightmares which economics has projected onto history. I just began to read this novel for teenagers, The Hunger Games, which is set in a dark future America. In the first few pages, I couldn’t get past the sense that I was reading another of the kinds of fables that economists use. It was another Robinson Crusoe story. It was a story in which all of the characters are atomised individuals – and in which this has intensified as people have got poorer. Which bears no clear relation to how people do continue to make life work during difficult times. The qualities of the highly-individualised self that this book starts out with are precisely the qualities that emerge among people who are able to use money to solve all of their problems.

To me, I think that is one of the greatest challenges to the emergence of a new commons taking root within countries like mine: people have bought into so much of what they’ve been told to believe about themselves. Even what we think we know about science and evolution, so much of it is entangled with projections of these economic stories about the competing lone individual. How does that begin to break down? Where do new-old concepts of the self begin to emerge?

GE: I think that this is already happening, because people have had enough of this hyper-individualism. And the good news is that, we have been constructed as individuals, we can feel that we are individuals, we can experience the world as individuals – but we are not! As Raimon Panikkar said very clearly, we are ‘knots in nets of relations’. This is what people are rediscovering, that we are really the relations. That behind this individual mask, the mask of ‘I am a mammal and this body is the body of animal, an individual body, a unique individual body’, behind this, what I find is an ‘I’ that is always a ‘we’. Because I am a collection of relations, my story of relations, my relations with other people. It is important to see how we have been constructed as individuals in order to abandon that idea.

I have been using one example. I don’t think that in Europe it is so famous, this book of Dr. Spock that is basically prepared for young couples who don’t know how to raise a child. It has a magnificent index about how to discover anything happening to the baby. For five years, the book has the catechism, the commandments for the young couple. First commandment: the parents’ bed is forbidden territory for the babies. They should never be there. Second commandment: it is very good, it’s really necessary, for the child to be alone in his or her own room as soon as possible. If possible, the day they come back from the hospital. Third commandment: it is very good for the physical and mental development and psychological development of the child to cry alone, at least half an hour a day. I imagine at some point the poor mother saying, ‘Oh god! Twenty minutes…Twenty-five minutes…I cannot bear this suffering of my poor child!’

Well, what kind of being is this baby? The very first day he is in the house, he’s being raised as an individual. Then you go to India, you go to Mexico and you see that fantastic invention of the shawl, the rebozo, in which the baby is attached to the body of the mother for months. But the mother is doing many things, is doing her own life with the baby, here, on her breast, close. That is a different kind of relation.

DH: In a sense, this is my question, because what we see in the West are generations of people who have been brought up according to one set of experts or another who are essentially guiding the formation of the atomised individual from the moment of arrival back from the hospital. That damage is inscribed into the adults. I often think that the subject that’s assumed by economics, Homo economicus, is actually the damaged child. The assumption of scarcity in every situation, that’s the behaviour of a child that has not had love and not been able to trust in early childhood. And this is normalised as what we are all meant to be like, what the marketers are teaching their students in marketing to manipulate.

So, how do we go from societies like Britain or Sweden or the United States, where most adults have had an upbringing that was calculated to produce the atomised individual? How do those atomised individuals re-learn the belonging within the larger we?

GE: I think it is happening, it is really happening. Millions of people are desperately looking for an alternative.

DH: There’s a hunger, certainly. There is a gap between what we’re told we are and what we feel we are. Often people don’t have a language for it, all they have is the sense that something’s not right. A sense that there’s meant to be more to life than this. Sometimes they’re then told: well, the sense that there’s meant to be more to life, this is a universal experience. ‘This is what life is. Life is the feeling that there ought to be more to life.’

But, there is … an opening. That gap is the place through which, when people then find things which help them make sense of their experience and don’t simply accept that sense of lack, there is a coming-alive that you see in them. I’ve certainly experienced that a lot in the work that I’ve been part of in Europe over the last few years.

Again, though, I come back to the anxiety which I think a lot of us feel: ‘But this is so small!’ This is little cracks in the corners, against the vastness of the ideology and the structures that exist to tell us that this, the horror as you call it, is all that there is or could be.

GE: That is why it is important to discover that we are not alone. We don’t see in the news the examples of people reclaiming the commons. From Peru, we did not hear that the indigenous people reclaimed one million hectares, one by one. One million hectares is a lot of land. Now they are producing 40% of their food in Peru within their own traditional system. That is reclaiming the commons.

But the most important thing, I think, for people in Europe is creating new commons. It is the people, particularly in the cities…We know we all have a thousand ‘friends,’ but real friends we have only two, three, four or five, perhaps eight friends. Here, I remember Illich again, he was talking all the time about his polyphilia, that was his thing, the need to be with friends. He elevated friendship as the main category for the reorganisation of the society, for reconstructing our society in a different way.

DH: The starting point of hope.

GE: Absolutely.

DH: I encounter a lot of people who are alive to the seriousness of the mess we’re in, alive to the horror, and who can’t put their faith in something as soft as friendship. Who say, ‘Our cities are three meals away from catastrophe because of the agro-industrial supply chain.’ Who say, ‘We’re looking at the climate predictions and, you know, we’re going to be lucky if we keep climate change down to four degrees by the end of the century. There’s a good chance it will be six. We will probably have, at best, half a billion people left on the planet at the end of the century.’ Many of the people I work closely with, this is the reality that is weighing on their minds, and it is very hard to…

GE: It is their reality? That is the problem.

DH: This is what they would say is the hard reality that we face. And it is very hard for them to hear what we are talking about, when we talk about friendship as the new commons, as the ground from which things grow. What do you say to them?

GE: How can we formulate the problems, the reality in a different way?

What I see in global warming, and the other horrors, this is a formulation that implies the continuation of the manic obsession of industrial man to be God. And, he failed. We are not gods.

To put this in a provocative way: it is, I would say, equally arrogant to affirm or deny global warming. In both cases, we pretend that we really know how the Earth is behaving. That we have all the information. First, that we know from the past how the Earth behaves. Second, that we know how the Earth will react. And third, that we know how to fix the problem.

That is too arrogant. To say, yes, there is global warming, or to say, no, there is no global warming: both positions are absolutely arrogant.

What we do know for sure, however – you and me and your friends and everyone – is that we have been doing something very wrong. That our behaviour is wrong. That our behaviour every day is wrong.

DH: If I understand what you are saying, then this connects to something that has troubled me about the way that climate change is talked about. Most of the time, there seems to be an implication – which the people who are most actively voicing it would not agree with – that, if it weren’t for the misfortune of the fragility of this global climate system, we could keep doing all of this. If it weren’t for the accidental, unforeseeable byproduct of what would otherwise have been Progress, then it would be fine. And I don’t know if any environmentalist, in their heart, believes that. But perhaps this is the arrogance you are talking about, the persistence of the god-like arrogance of industrial man, even within the way we talk about the horror of the mess we have made of the world?

GE: At the same time you have the best scientists in Germany at the Wuppertal Institute, after five years and a great amount of funding, they presented a most radical proposal: they suggested the reduction of the consumption of everything by 90%. That is really more radical than any other environmentalists. But, basically, to avoid any change!

DH: Yes, to achieve a version of how we live now which is as close as possible to how we live now, but without doing the damage on that particular front.

GE: That is what we need to stop doing. We cannot continue in that path. Because after two or three great disasters, a few tsunamis or Fukushimas – after that, some people will say: well, given the irresponsibility of the 7 billion people, what we need is a good, global authoritarian government to save poor Mother Earth. Then we will have control over everyone. And many people will say, ‘Oh yes, finally something is being done!’

DH: It’s true, those arguments are starting to be voiced.

GE: That is part of the horror. That is why the horror is inside us. It’s not only outside. It’s not just the powers that be, we have been infected with it. Then we need to stop. But I think, again, people are doing that. I think that there are millions of people saying, ‘No, I need to stop by myself,’ doing whatever it is.

DH: This is one of the things that Paul and I have encountered with Dark Mountain, over the last few years. The response to what we’ve been doing has been incredibly polarised. It’s been polarised between relief and anger. Relief from people who feel like they have been given permission to be honest, to voice their misgivings about where we had ended up, in an environmentalism that had ended up focused on calculative rationality and engineering solutions. And anger from those for whom it is absolute heresy to admit the limits of our ability to control things. There is a real problem in Western culture of not being able to conceive of any gap between control and despair. Either we can take control of a situation, or we’re in hell and we might as well curl up and die right now. It is difficult for people, particularly in the West, particularly in the environmental movement, to hear the idea of letting go of the illusion of control as anything other than giving up.

GE: Well, instead of talking in general about global warming and these statistics, let’s bring it down to things that matter for all of us. Like what is happening with food today. There is a poem by Eduardo Galeano which says: in these times of global fear, there are some people afraid of hunger, and the others are afraid of eating. There is a very real reason to be afraid of hunger, in every country. It’s not just a question of poor countries. In Britain or the United States, there are people who are afraid of hunger today because they do not know what will happen next month. The others are afraid of eating, why? Because we know what is in our plates. Our bodies are already poisoned, infected. It is not only junk food, it’s not only that it is not nourishing, it is full of poison, things that are damaging our health. And then, what … are we going to hope that the G8, the G7, the G20 or whatever will control the agribusiness and will stop what is happening, fix it? Are we hoping that Monsanto and Walmart will have a kind of moral epiphany and will stop doing what they are doing?

DH: I think the reality is that people aren’t hoping at all. But what they are fearing is, firstly, that there are 7 billion people on the planet now. People say to me, ‘You can’t feed that number of people without the agro-industrial complex: the only reason why the global population has got so big is because these agro-industrial technologies have enabled us to feed so many more people than the Earth can feed on its own.’ That’s the first fear that is very prevalent, when people think about this. And the second is almost a culture-level fear, that says, ‘Peasant life is nasty, brutish and short – and you’re saying that we should go back to that life?’

GE: I can understand, because that has been constructed in our minds for many, many years, particularly in the North. Since the 1970s it was constructed that way. That’s when hunger became the great business of the century and justified all the subsidies for food in Europe and the United States: they started to talk about ‘food power’ and hunger and all these kind of things.

But we need to see the alternative picture. First, one figure that is not well known: more than half of what we eat today in the world is produced by the people themselves. Not by Monsanto, not by agribusiness, not by the big companies: it’s by the people themselves. The Via Campesina, the biggest organisation in history, they have been talking about this figure. They know it, because they are part of these millions that are producing their own food. They defined the idea of ‘food sovereignty’: it’s not the market and it’s not the state that must tell us what to eat, but we must find it and produce it by ourselves.

But this is not going to be the back-to-the-land movement of the ’60s. First of all, because now more than 50% of the people on Earth are urban, we cannot produce food for everyone in the countryside. We need to produce food in the cities. And the beautiful thing is that it is absolutely possible. One hundred years ago, Paris was exporting food. Today, people are discovering that producing food in the cities is not only very simple but it is very beautiful.

* * *

GE: As you know, one Mr. Crapper invented for Queen Victoria what we now know as the water closet, the first toilet and the whole thing of the sewerage, and this clearly reformulated the whole urban environment. First of all I must say that this is very, very modern. In 1945, in the most advanced country, which was the United States, only a third of the people had sewerage. This clearly is something very modern that reformulated all the cities and created a real addiction to the flush toilet. There are some people who cannot live without the flush toilet. For them, it’s a fundamental need. But now there are many environmentalists seeing that it was a very wrong decision, that it was a very stupid technology, that it is doing more damage than cars to the environment. When you mix these three marvellous substances, shit, urine and water, you are creating a poisonous cocktail that contaminates everything. It’s a problem of public health, of cost, everything…

DH: It’s a waste of all three things that can, if handled better, be put to better use. But it’s not just that, it’s that once you have the flush toilet you are connected to a system. Think of the nightmare of The Matrix, with everyone in their tanks, stuck full of tubes, plugged in to this virtual reality. Part of why that nightmare haunts us it that is such a good description of what we take for granted: the kind of relationship we have to infrastructure is a relationship of dependence on unthinkably large, centralised systems. It’s not just that we are born into incubators where we’re stuck full of tubes, or that we die stuck full of tubes. It’s that we plug ourselves in to tubes at critical junctures in our life, every day.

GE: We wash our hands and that’s it, we don’t see how we are connected. When we create our composting toilets, this is about how to disconnect your stomach from any centralised bureaucracy. What is the feeling of political revelation that you have, when you don’t have those tubes and when you are not controlled!

DH: You’re dealing with your own shit.

GE: That is the fundamental question. Are we ready to deal with our own shit?

Another story that usually is very counterproductive, I don’t know if you can include this. I was visiting a magnificent group of people in Mexico City after the earthquake, reconstructing their houses. It was really an incredible group of 48 families working together for the reconstruction. I came one day to visit them with a colleague from my office, a woman, and then we found them very excited, in an assembly, discussing the problem. That morning one guy, one of them, attempted to rape a four-year-old girl of the community. He could not conclude the thing because they found him when he was trying to do that. They of course immediately examined the girl, the girl has no physical harm, and then they had him in a room and they were discussing what to do.

My colleague and I say, ‘But what are you discussing? You need to call the police to put this guy in jail!’

And then they immediately reject this, saying, ‘What is the purpose? To transform him into a criminal?’

Then my colleague did not know what to say. ‘Well, at least you need to send him to a psychiatric clinic because he’s a very sick guy. It’s a clear pathology.’

‘What is the purpose? To transform him into a fool?’

She did not know how to react and they continued discussing and then someone suggested, ‘Let’s send him to another neighbourhood.’ And then the others say, ‘No, that will be absolutely unfair for the other neighbours, because they will not know what was happening.’

And then, after four hours of discussion they came to the conclusion, let’s keep him, if the mother of the girl accepts. Then the mother accepted and the guy stayed.

Ten years later, I came back, I saw the girl was flourishing with an incredible amount of love that she got in the neighbourhood. The guy had married with another young woman of the place and they said she had already two children and they said they became the best neighbours of the group.

I’m telling this terrible story just to ask this question: are we ready to deal with our own shit? Because it is not just the physical shit, it’s the moral shit.

DH: The metaphor is so close because the institutional way of dealing with such a situation, whether it’s through the courts or through the psychiatric system, has the apparent virtue of allowing everyone else to wash their hands. It is pulling the chain and the shit is being taken somewhere else. It looks clean and powerful and efficient. But what are the chances of the shit actually being allowed to decay into something that contributes to the ongoing life of the community, rather than coming back to haunt it?

Published in Dark Mountain: Issue 4.