One night in late September, I had the chance to speak with Joanna Harcourt-Smith for her Future Primitive podcast. This was a meeting between generations: Joanna lived through the wild heart of the 1960s counterculture in California and its aftermath, something we touch on at points in our conversation. It was also a chance to talk about the journey from Dark Mountain to a school called HOME, as well as The Curious Tale of Boris Johnson’s Heart, which I was in the middle of writing.

Tag: the sacred

-

Believing in Holidays: A Conversation with Elizabeth Slade

An extract from ‘The God-Shaped Hole’ by Elizabeth Slade

We sit on cushions in a circle, about 25 of us surrounding one lit candle. Each of us is invited to place a personal object in the middle. Some put jewellery, a hat, a piece of quartz. I stay still, very conscious of being in a minority: not wearing yoga pants, not barefoot, no piercings or tattoos. I’m wearing a top from Whistles, for fuck’s sake.

I feel the stiffening in my shoulders as a wave of discomfort passes over me. My cheeks flush with embarrassment – what would the me of just a few years ago have made of this situation?

Now, I’m able to notice the discomfort, let it go (mostly), or just be OK with noticing it. I know that through the discomfort the good stuff lies. I notice my desire to stay in a safe, practical, intellectual, rigid, mask-wearing state, and I gently try to put these elements down.

The work involves sharing meaningful personal stories with each other. Gazing into the eyes of strangers. Exploring political issues that we care deeply about and retelling them from different personal angles. We’re firmly in the emotional and out of the intellectual.

This is London, days after the Grenfell Tower fire. Everyone has a lot of pain.

And when the workshop is over, back in the circle around the candle and altar of objects, we all feel connected. It’s like our hearts are bigger than they were at the start. There is an undeniable connection between all people, all life. Afterwards, it occurs to me that this is the third role of the sacred: between the sky of possibility and the ground of being held, to encourage the felt knowledge of connection.

When big events come, a hunger for connection breaks the surface of our current way of living. I remember the 7/7 bombings in London back in 2005, long before I had any interest in the sacred. That sunny day, after news of what happened spread, everyone left work early to slowly make their way home and it was inarguably apparent that we’d all go to the pub. I look at something I wrote back then: ‘In earlier days (or in America), people would have gathered their families together and prayed. In London, we got our mates together and drank.’ It was a kind of communion, I guess.

Last November, on the day we learnt that Donald Trump was going to be president, my minister opened the church for the evening. About fifteen of us sat in candlelight and shared how we felt, and a violinist played exactly the right music, and we wept. Brits, Americans, people in their twenties and their eighties, all feeling the need to be together.

On days like that, people recognise the need to be close to others, to gather together while they’re hurting or scared, for their emotions to be held in the right way, whether oiled by beer, or by candlelight and violin and the work of an experienced minister. It feels like a very basic human thing, so I assume we had the words for it long before the language of church.

A conversation

DH – What you’re saying in the piece is that, until the last fifty or sixty years, in our part of the world, it was very normal that lots of people were part of a local church. That was part of the fabric of society, and it went away pretty quickly. And maybe we haven’t got the measure of some of what was lost, things that aren’t necessarily to do with your big cosmic beliefs about the Universe, but about some basic human needs. You draw on your own experiences with new kinds of non-religious gathering spaces like Sunday Assembly, as well as your local Unitarian church, where the minister is an atheist who used to be a scientist at MIT – but you’re also looking at it from the perspective of the work you’ve done with public health?

ES – Absolutely. So some of the work that I’ve done has been around the limitations of the health care system. You know, if you’ve broken a leg or something, it’s really well geared-up to treat you. But doctors have known for a long time that so much of what makes us healthy happens outside of biomedical health. It’s more to do with how we live – and that’s so much more than just, take more exercise, stop smoking, don’t eat as many doughnuts! We can live in ways that create health and that has a lot to do with how we live in our communities and the sense of purpose that we have in our lives. All those things that are not well provided for either by the state or the market. And right now, we can’t see what we’re missing, because there’s been this sort of generational gap there. There’s not a lot of common language to talk about these aspects of our lives.

DH – You’ve been thinking about the role of serving a community that might have been played once upon a time by somebody who wore a strange collar and stood up in front of a building full of people on a Sunday morning. And it’s not necessarily a desire to herd everybody back into churches that you’re talking about, but a sense that there is a role there that we need in other ways and haven’t necessarily got good at recovering?

ES – Yeah, definitely. And the language does get in the way and I’m really conscious that I use a lot of church-based language which to a lot of people is either alien or meaningless. But yes, there is a kind of role of ministry. I don’t think there’s an appetite in our culture to have someone who stands up in front and has all the answers – I think there’s something a bit repulsive about that idea – but we can be equipped to support each other, to be each other’s ministers and spiritual guides and help each other through life. And people are doing that, but it’s not yet a role that’s really valued in our culture. It’s not really something that’s seen. So you know, back when I went into the church for the first time, I didn’t feel: oh, I really need some kind of counsel from a minister. I didn’t really know what it was I wanted, I just had a sense of a gap, but it feels like it would be a hugely valuable thing if it was like, oh, I need a bit of guidance – I need to go and speak to someone who is in one of these community leadership roles with certain skills and knowledge. It would be good if we had some understanding, some way of talking about this, as a culture.

DH – It strikes me there are skills that in other times and places would have been regarded as something that you spent twenty years of your life learning how to do, before you were let loose as somebody could practice, where now we think you can go on a few weekend courses and get a certificate that allows you to sell your services – and that’s true whether we’re talking about some of the things that go under the name of ‘hosting’ and ‘facilitation’ these days, or whether we talk about some of the more New Age spiritual services that are on offer. So I wonder, without simply copying and pasting from the way things have been done in the past or in other cultures, how do we home in on a less flimsy way of dealing with these parts of being human?

ES – Thinking about the health care example, there’s been a lot of discussion in the last few years, reminding nurses and doctors alike, ‘Oh, we should be caring and compassionate.’ And you know a lot of people go into those roles because they are caring and compassionate – but actually, if the culture of the organisation loses its way and focuses on the hard clinical outcomes and the costs and all of that stuff and forgets ‘Oh, we’re here to be caring and compassionate’, then you have to remind people to do it. And so, in this sort of new, post-church spiritual world, there’s a sense of there not being much of an appetite for dogma. You don’t really want to say, ‘Oh yes, we all believe this, we all believe the same thing and these are the rules.’ But there is a danger of exploitation, people using powerful tools and techniques from the world of the sacred for their own gain, or just using them clumsily.

DH – We’ve been talking about how removed our culture has become from the experience of what you’re saying the church, at its best, used to provide. But there’s also a rediscovery going on in lots of places of what you might call the technology of the sacred – ritual, the mountaintop experience, the things that take you to those wild beautiful moments of meaning – which is often drawing on knowledge and practice that has existed within religious or spiritual cultural traditions. Maybe it’s tempting for us, as these things are being rediscovered, to focus on these ecstatic experiences?

ES – Yeah and you can see why, because it feels like that’s where the action’s happening. It’s exciting to be part of a ritual where you enter a different world for a little while and you know that the people around you are also entering that different world, that different mind-set, for a little while. And all of that stuff is hugely valuable – and still I think it’s a very tiny slice of the whole picture and actually the value is much more in the slow, gentle, day-to-day engagement with the sacred. Which can’t be these euphoric experiences, you know. You can’t have Christmas every day.

DH – You can’t live on a mountaintop. You go there to spend four days in retreat and have a powerful experience, but you still come back, hopefully to somewhere more sheltered.

ES – If the thing that you’re looking for is the euphoric experience and you’re looking to find it in a way that fits your everyday life in a sustainable way, I don’t believe that’s possible. So it’s more about accepting the slow and gentle, day-to-day, and having the things in your life that make that sustainable. Rather than just like, oh, if I can just get through to Christmas, then I can get through all of this difficult stuff that I know I’ve got on, but you know, just around the next corner, I’ll be OK. A lot of our culture at the moment is – oh, get through to your next holiday, get through to the weekend. You know, wait till you get home and you can have a glass of wine. And yeah, I guess I was totally in that pattern of living, pre-church, and I’m not entirely not within that pattern of living now, I guess! But I totally see that those bits of cultural infrastructure that you can bring into your day-to-day, just help us cope with this brilliance of being human so much better. Because it feels like we’re missing a lot of the sort of struts and supports that would really help us, I guess, stay level.

DH – Where I’m sitting, it’s also about coping with – or just not cutting ourselves off from – some of the darkness of what it means to be living at this moment. Living with the paradox that our ways of life are tangled up with processes that we’ve set in motion that are making it hard to imagine that we’ll be able to go on living like this – you know, it’s hard to imagine that this is going to be made sustainable. And at the same time, as you describe it, there’s a lot within even the privileged, successful version of that way of life which is not worthy of being sustained. Because living for the weekend, living for the next holiday, that doesn’t seem much like making a good job of being a culture.

ES – Exactly, it’s just deferring, isn’t it? It’s like, we don’t believe in heaven anymore, but we do believe in holidays.

Published on Dark Mountain’s Online Edition to accompany the release of SANCTUM, a special issue on ‘the sacred’.

-

Childish Things

It was September and I hadn’t seen Ruben all summer, but there he was, the same as ever, gangly and lounging, his hair cropped almost to the bone, his eyes alert; a kid from the wrong side of town who turns the skills his childhood taught him into art. That summer, I’d become a father. The weeks of July and August tightened into the small world of our new family, living by old rhythms of bodily need. (I must have said something about this – about the way it shatters whatever illusions you had of your own centrality, how it locks you into the chain of generations and releases you from any compulsion to make your one life a story in itself.) And I asked him, ‘So, how was your summer? What have you been up to?’

‘I gave my sermon on the mount,’ he said, like it was a matter of fact, and it turned out that it was.

One Friday night, 150 mostly young people had followed him up a rocky hill on the edge of town (the town where he grew up, an hour south of Stockholm) to where the birch trees clear, and they sat on the ground and listened as he spoke. There were no flowing robes; he wore an Adidas tracksuit top and carried a binder with his notes. He wasn’t playing the messiah, trying to start a cult; nor was he playing the artist, making a point by appropriating the forms of religion. As the sun went down over the pines, he talked about life as a journey through the woods at dusk, each of us carrying a pocket-light of reason: its beam cuts a bright tunnel, but throws everything outside this tunnel into darkness; if we use it thoughtlessly, we forget that we have other senses with which to find our way.

When the sermon and the discussion that followed were at an end, the congregation made their way quietly down among the trees, the twilight deepening around them.

* * *

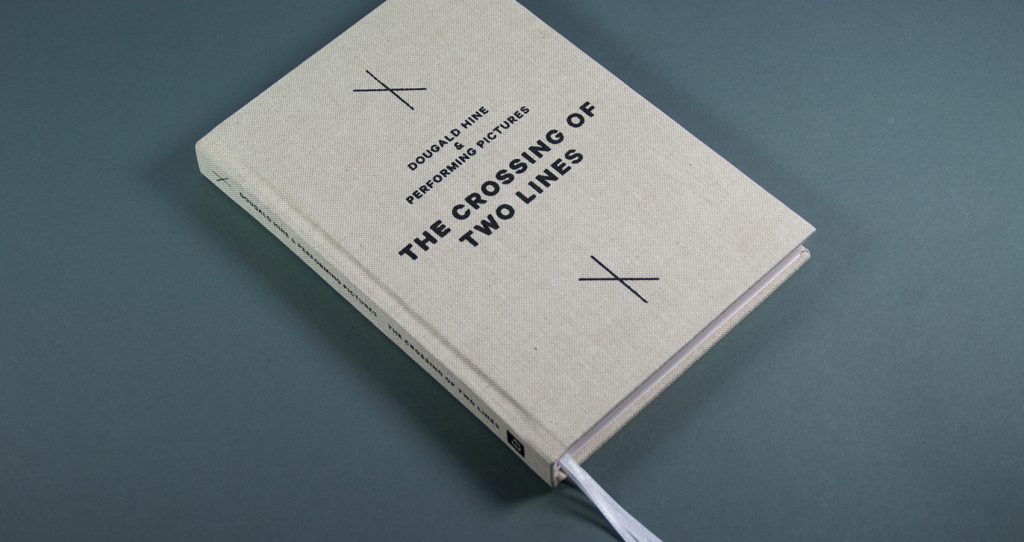

A few years before, I had made a book with the video artists Robert and Geska Brečević, who operate as Performing Pictures. Around the time we met, their work took an unexpected turn as they began collaborating with craftworkers in Oaxaca and Croatia, building roadside chapels and producing video shrines that set the saints in motion. Our book was a document of this work but also an enquiry into how it came about, what had drawn them to the folk Catholicism of the villages where they were now working, and the reactions this had provoked among their art-world contemporaries. About these reactions, I wrote:

We are used to art that employs the symbols of religion in ways seemingly intended to unsettle or provoke many of those to whom these symbols matter. Yet to the consumers of contemporary art, those who actually visit galleries, it is more uncomfortable to be confronted with work in which such symbols are used without the frame of provocation.

That may still be the case, yet these days I am struck by how many of the artists, writers and performers I meet find themselves drawn to the forms and practices of religion.

I think of Ben who went off to Italy to start an ‘unMonastery’, a working community of artists in service to its neighbours. The name suggested a desire to distance themselves from the example of the religious community, even as they found inspiration there. A couple of years facing the difficult realities of holding a community together, however, deepened their appreciation for the achievement of those who had maintained monasteries for generations, and this was reflected in a series of conversations which Ben went on to publish with abbots of established religious orders.

For some, it’s a question of taking on the roles religion used to play, using the tools of ritual to address the ultimate. When I run into Emelie, a choreographer friend, she’s just back from a small town in the middle of Sweden where a group of artists has taken over the old mine buildings. It’s the kind of place that lost its purpose with the passing of the industry which called it into being. The project started with two brothers who grew up there – and this weekend, they have been celebrating the younger brother’s birthday. The way I hear it, the celebration was a three-day ritual which saw participants building their own coffins only to be lowered into them, emerging after several hours to be greeted with music and lights and a restorative draught of vodka.

In another mining town a thousand miles away, Rachel Horne made her first artwork at the site of the colliery where four generations of her family had worked. Out of Darkness, Light was a memorial event: one night on the grassed-over slag heap above the town, 410 lamps were lit, one for each of the men and boys who died in the century in which coal was mined there. On a boat travelling along the river below, a group of ex-miners and their children told their stories. This was art as ritual, honouring the dead in such a way as to bring meaning to the living.

Last time I spoke to Rachel, we talked about an event that she had put on a few weeks earlier. ‘You know,’ she said with a sigh, ‘it was like organising a wedding!’ I knew: months of energy building up to a big day and afterwards everyone involved is exhausted. Weddings are great, but how many do you want to have in a lifetime? It hit me, as artists we’re good at ‘weddings’, but sometimes what’s called for is the simplicity of the weekly Sunday service. Soon afterwards, I came to a passage in Chris Goode’s The Field and the Forest where he quotes a fellow theatre-maker, Andy Smith:

Every week my mum and dad and some other people get together in a big room in the middle of the village where they live. They say hello to each other and catch up on how they are doing informally. Then some other things happen. A designated person talks about some stuff. They sing a few songs together. There is also a section called ‘the notices’ where they hear information about stuff that is happening. Then they sometimes have a cup of tea and carry on the chat.

Both Smith and Goode are impressed by the resemblances between the Sunday service and the kinds of space they want to make with theatre. The connection is not made explicit, but when Goode ends his book with a vision of a ‘world-changing’ theatre where ‘once a fortnight at least, there’s someone on every street who’s making their kitchen or their garage or the bit of common ground in front of their estate into a theatre for the evening’, I think back to that passage and the distinction between the wedding and the weekly service.

* * *

I could go on for a while yet, piling up examples, but it’s time to pull back and see where this might get us. The artists I’ve mentioned are all friends, or friends of friends, so I can’t pretend to have made an objective survey. I don’t even know if such a survey could be made, since much of what I’m describing takes place outside the official spaces of art. Even the objects produced by Performing Pictures, though they sometimes hang in galleries, are made to be installed in a church or at a roadside.

There is nothing new, exactly, about artists tangling with the sacred – indeed, the history of this entanglement is the thread I plan to follow through these pages. Yet here in the end-times of modernity, under the shadow of climate change, I want to voice the possibility that these threads are being pulled into a new configuration. There’s something sober – pragmatic, even – about the way I see artists working with the material of religion. The desire to shock is gone, along with the skittering ironies of postmodernism; and if ritual is employed, it is not in pursuit of mystical ecstasy or enlightened detachment, but as a tool for facing the darkness. I’m struck, too, by a willingness to work with the material of Western religious tradition, with all its uncomfortable baggage, rather than joining the generations of European artists, poets and theatre-makers who found consolation in various flavours of orientalism.

All this has set me wondering: what if the times in which we find ourselves call for some new reckoning with the sacred? What if art is carrying part of what is called for? And what if answering the call means sacrificing our ideas about what it means to be an artist?

A Strange Way of Talking About Art

We have been making art for at least as long as we have been human. Ellen Dissanayake has made a lifelong study of the role of art within the evolution of the human animal, and she is emphatic about this:

Although no one art is found in every society … there is found universally in every human group that exists today, or is known to have existed, the tendency to display and respond to one or usually more of what are called the arts: dancing, singing, carving, dramatizing, decorating, poeticizing speech, image making.

Yet the way such activity gets talked about went through an odd shift about 250 years ago. In Germany, France and Britain, just as the Industrial Revolution was getting underway – and with colonialism pushing Western ideas to the far corners of the world – a newly extravagant language grew up around art. The literary critic John Carey offers a collage of this kind of language, drawn from philosophers, artists and fellow critics:

The arts, it is claimed, are ‘sacred’, they ‘unite us with the Supreme Being’, they are ‘the visible appearance of God’s kingdom on earth’, they ‘breathe spiritual dispositions’ into us, they ‘inspire love in the highest part of the soul’, they have ‘a higher reality and more veritable existence’ than ordinary life, they express the ‘eternal’ and ‘infinite’, and they ‘reveal the innermost nature of the world’.

Bound up with this new way of talking is the figure of the artistic genius. There have always been masters, artists whose skill earns them a place in the memory of a culture. In his account of the classical Haida mythtellers, the poet and linguist Robert Bringhurst is at pains to stress the role of individual talent within an oral literature, where a modern reader might expect to encounter the nameless collective voice of tradition. Yet a fierce respect for mastery does not presuppose a special kind of person whose inborn capacity makes them, and them alone, capable of work that qualifies as ‘art’. Rather, as Dissanayake shows, in most human cultures, it has been the norm for just about everyone to be a participant in and appreciator of artistic activity.

The ideas about art which took hold in Western Europe in the late 18th century spread outwards through cultural and educational institutions built in Europe’s image. Were anyone to point out their peculiarity, it need not have troubled their proponents, for the contrasting ideas of other cultures could be assigned to a more primitive phase of development. Today, that sense of superiority has weakened and become unfashionable, although it remains implicit in much of the thinking that shapes the world. Under present conditions, a critic like Carey can take glee in mocking the heightened terms in which Kant and Hegel and Schopenhauer wrote about art; yet the result is a deadlocked culture war in which defenders of a high modern ideal of art are pitched against the relativists at the gates.

Rather than pick a side in this battle, it might be more helpful to ask why art and the figure of the artist should take on this heightened quality at the moment in history when they did. If a new weight falls onto the shoulders of the artist-as-genius, if the terms in which art is talked about become charged with a new intensity, then what is the gap which art is being asked to fill?

That the answer has something to do with religion is suggested not only by the examples which Carey assembles, but also by the sense that he is playing Richard Dawkins to the outraged true believers in high art. And there have been those, no doubt, for whom art has played the role of religion for a secular age. But this hardly gets below the surface of the matter; the roots go further down in the soil of history. It is time to do a little digging.

The Elimination of Ambiguity

In 1696, an Irishman by the name of John Toland published a treatise entitled Christianity Not Mysterious. This was just one among a flurry of such books and pamphlets issuing from the London presses in the last years of the century, but its title is emblematic of the turn that was taking place as Europe approached the Enlightenment: a turn away from mystery, ambiguity and mythic thinking.

As the impact of the scientific revolution reverberated through intellectual culture, the immediate effect was not to undermine existing religious beliefs but to suggest the possibility of putting them on a new footing. If Newton could capture the mysterious workings of gravity with the tools of mathematics, then the laws governing other invisible forces could be discovered. In due course, this would lead to a mechanical account of the workings of the universe, stretching all the way back to God.

In its fullest form, this clockwork cosmology became known as deism: a cold reworking of monotheistic belief, offering neither the possibility of a relationship with a loving creator, nor the firepower of a jealous sky-father protecting his chosen people. The role of the deity was reduced to that of ‘first cause’, setting the chain reaction of the universe in motion. Stripped of miracles, scripture and revelation, deism never took the form of an organised religion or gained a substantial following. It attracted many prominent intellectual and literary figures in England, however, in the first half of the 18th century, before spreading to France and America, where it infused the philosophical and political radicalism which gave birth to revolutions.

The religious establishment recoiled from deism and its explicit repudiation of traditional doctrine. Yet mainstream Christianity was travelling the same road, accommodating its cosmology to the new science in the name of natural theology, applying the tools of historical research to its scriptures and seeking to demonstrate the reasonableness of its beliefs. The result was a form of religion peculiarly vulnerable to the double earthquake which was to come from the study of geology and natural history. Imagine instead that the rocks had given up their secrets of deep time to a culture shaped by the mythic cosmology of Hinduism: the discovery would hardly have caused the collective crisis of faith which was to shake the intellectual world of Europe in the 19th century.

To this day we live with the legacy of this collision between naturalised religion and the revelations of evolutionary science; militant atheists clash with biblical literalists, united in their conviction that the opening chapters of Genesis are intended to be read as a physics and biology textbook. It is an approach to the Bible barely conceivable before the 17th century.

* * *

Mystery can be the refuge of scoundrels; ambiguity, a cloak for muddle-headedness. The sacred has often been invoked as a way of closing off enquiry or to protect the interests of the powerful. We can acknowledge all of this and deplore it without discarding the possibility that reality is – in some important sense – mysterious. It takes quite a leap of faith, after all, to assume that a universe as vast and old as this one ought to be fully comprehensible to the minds of creatures like you and me.

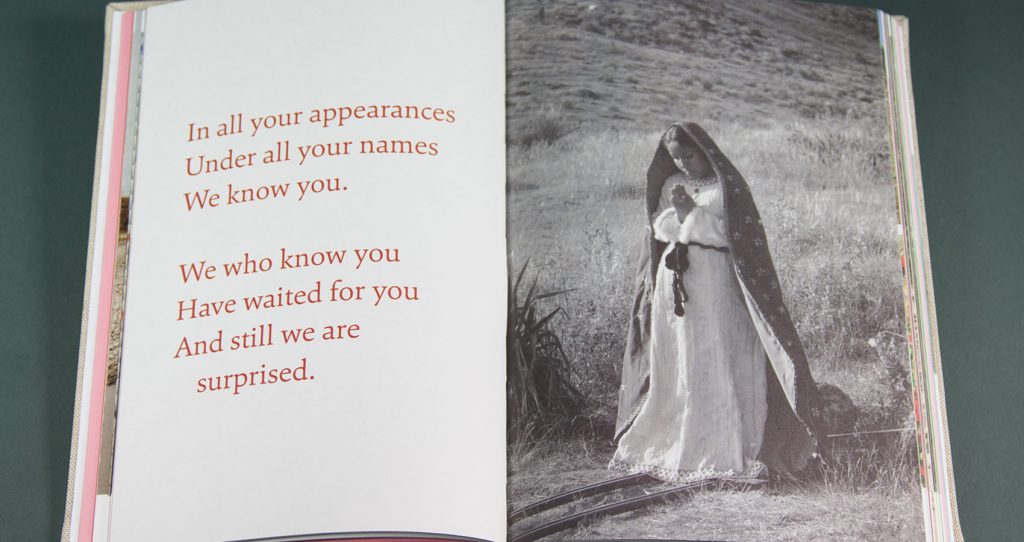

Among the roles of religion has been to equip us for living with mystery. This is not just about filling the gaps in current scientific knowledge or offering comforting stories about our place in the world. Across many different traditions there is an underlying attitude to reality: a common assumption that our lives are entangled with things which exceed our grasp, which cannot be known fully or directly – and that these things may nonetheless be experienced and approached, at times, by subtler and more indirect means.

This attitude shows up in the deliberate strangeness of the way that language is used in relation to the sacred. The thousand names of Vishnu, the ninety-nine names of Allah: the multiplication of such litanies hints at the limits of language, reminding us that words may reach towards the divine but never fully comprehend it. A similar effect is achieved by the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God in the Hebrew Bible, written without vowels so as to be literally unspeakable.

For Christians, a classic expression of this attitude to reality appears in Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, from the chapter on love that gets read at weddings:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (1 Corinthians 13:11–12)

The emphasis is on the partial nature of knowledge: in relation to the ultimate, our understanding is childlike, a dark reflection of things we cannot see face-to-face. The most memorable of English translations, the King James Version gives us the image of a ‘glass’, but the mirror which Paul has in mind would have been of polished brass. Indeed, it is carefully chosen, for the Greek city of Corinth was a centre for the manufacture of such mirrors.

The thought that there are aspects of reality which can be known only as a dark reflection calls up another Greek image. The myth of Perseus is set in motion when the hero is given the seemingly impossible task of capturing the head of the Gorgon Medusa, whose gaze turns all who look on her to stone. The goddess Athena equips Perseus with a polished shield; by the reflection of this device, he is able to approach the monster, hack off her hissing head and bag it safely up. In the shield of Perseus we glimpse the power of mythic thinking: by way of images, myth offers us indirect means of approaching those aspects of reality to which no direct approach can be made.

Few passages in the Bible are more at odds with the spirit of the Enlightenment than Paul’s claim about the limits of human knowledge. To put away childish things was the ambition of an age in which the light of reason would shine into every corner of reality. What need now for dark reflections – or mythic shields, for that matter? By the turn of the 18th century, such things were no longer intellectually respectable: the unknown could be divided into terra incognita, merely awaiting the profitable advance of human knowledge, and old wives’ tales that were to be brushed away like cobwebs.

The institutional forms of religion were capable of surviving this turn away from mystery, though much was lost along the way, and none of the later English translations of the Bible can match the poetry of the King James. Meanwhile, if anyone were to go on lighting candles at the altars of ambiguity, it would be the poets and the artists, the ones upon whose shoulders a new weight of expectation was soon to fall.

Toys in the Attic

When the educated minds of Europe decided that humankind had come of age, the immediate consequence for art was a loss of status. If all that is real is capable of being known directly, then the role of images and stories as indirect ways of knowing can be set aside, relegated to entertainment or decoration.

I say immediate, but of course there was no collective moment of decision; we are dealing rather with the deep tectonic shifts which take place below the surface fashions of a culture, and the extent to which the ground has moved may be gauged as much through the discovery of what was once and is no longer possible, like the epic poem. The pre-eminent English poet of the first half of the 18th century, Alexander Pope aspired to match the achievement of Milton’s Paradise Lost by producing an epic on the life of Brutus; yet, despite years of telling friends that the project was nearing completion, all that he left upon his death was a fragment of eight lines. The failure seems more than personal, as though the mythic grandeur of the form was no longer available in the way it had been a lifetime earlier.

In Paris in 1697, a year after Christianity Not Mysterious had rolled off the London presses, Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé launched the fairy tale genre, committing the stories of oral tradition to print with newly added morals. By the time the first English translation was printed in 1729 – ‘for J. Pote, at Sir Isaac New-ton’s Head, near Suffolk Street, Charing Cross’ – the publisher could advertise Perrault’s tales as ‘very entertaining and instructive for children’. Stories which had been everyone’s, which carry layers of meaning by which to navigate the darkest corners of human experience, had now been tamed and packed off to the nursery.

Meanwhile, a strange new form of storytelling arose which put a premium on uneventful description of the everyday and regarded unlikely events with suspicion. ‘Within the pages of a novel,’ writes Amitav Ghosh, ‘an event that is only slightly improbable in real life – say, an unexpected encounter with a long-lost childhood friend – may seem wildly unlikely: the writer will have to work hard to make it appear persuasive.’ A masterful novelist himself, Ghosh is nonetheless troubled by the 18th-century assumptions encoded within the form in which he writes. What troubles him most is the thought that these assumptions underlie the failure of the contemporary imagination in the face of climate change.

In the kinds of story which our culture likes to take seriously, all of the actors are human and most of the action takes place indoors. Such realism is ill-equipped to handle the extreme realities of a world in which our lives have become entangled with invisible forces, planetary in scale, which break unpredictably across the everyday pattern of our lives. The writer who wants to tell stories that are true to this experience had better go rummaging in the attic where the shield of Perseus gathers dust among the toys, the sci-fi trilogies devoured in teenage weekends and the so-called children’s literature where potent materials exiled to the nursery grew new tusks.

But writer, beware: the boundaries of the serious literary novel are still policed against intrusions of myth or mystery, and the terms used to police them are telling. In notes for a never-finished review of Brideshead Revisited, written on his own deathbed, George Orwell marks his admiration for Waugh as a novelist, but then comes the breaking point: ‘Last scene, where the unconscious man makes the sign of the Cross … One cannot really be Catholic and a grown-up.’ Almost half a century later, Alan Garner met with the same charge when his novel Strandloper was published as adult literary fiction. The Guardian’s reviewer, Jenny Turner, found the author guilty of crossing a line with his insistence on depicting Aboriginal culture on its own terms:

… such a phantastic view of history cannot ever rationally be made to stand up. This underlying irrationality usually works all right in poetry, which no one expects to make a lot of sense. It’s okay in children’s writing, which no one expects to be psychologically complex. But in a grown-up novel for grown-ups, it just never seems to work.

Carrying the Flame

As Paganini … appeared in public, the world wonderingly looked upon him as a super-being. The excitement that he caused was so unusual, the magic he practised upon the fantasy of the hearers so powerful, that they could not satisfy themselves with a natural explanation.

So wrote Franz Liszt on Paganini’s death in 1840. The Italian violinist and composer had been the model of a virtuoso: a dazzling performer who stuns audiences with technical audacity and sheer force of personality. The term itself had taken on its modern meaning within his lifetime, shaped by his example. In those same years, an unprecedented cult of personality grew up around the Romantic poets, while in the theatres of Paris and London a strange new convention had emerged, according to which audiences sat in reverential silence before the performers; half a century earlier, theatres were still such rowdy spaces that an actor would be called to the front of the stage to repeat a favourite speech to the hoots or cheers of the crowd.

A new sense was emerging of the artist as a special category of human. The conditions for this had been building for a long time. In ‘Past Seen from a Possible Future’, John Berger argues that the gap between the masterpiece and the average work has nowhere been so great as within the tradition of European oil painting, especially after the 16th century:

The average work … was produced cynically: that is to say its content, its message, the values it was nominally upholding, were less meaningful for the producer than the finishing of the commission. Hack work is not the result of clumsiness or provincialism: it is the result of the market making more insistent demands than the job.

Under these conditions, to be a master was not simply to stand taller than those around you, but to be looking in another direction. In the language of Berger’s essay, such masterworks ‘bear witness to their artists’ intuitive awareness that life was larger’ than allowed for in the traditions of ‘realism’ – or the accounts of reality – available within the culture in which they were operating. Dismissed from these accounts were those aspects of reality ‘which cannot be appropriated’.

Berger warns against making such exceptions representative of the tradition: the study of the norms constraining the average artist will tell us more about what was going on within European society. Still, exceptionality of achievement fuelled the Romantic idea of the artist set apart from the rest of society. If the Enlightenment established lasting boundaries around what it is intellectually respectable for a ‘grown-up’ to take seriously, then the Romantic movement inaugurated a countercurrent which has proven as enduring. In Culture and Society, Raymond Williams identifies a constellation of words – ‘creative’, ‘original’ and ‘genius’ among them – which took on their current meanings in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as part of this new way of talking about the figure of the artist.

The artists themselves were active in creating this identity. Here is Wordsworth, in 1815, addressing the painter Benjamin Haydon:

High is our calling, Friend! – Creative Art …

Demands the service of a mind and heart

Though sensitive, yet in their weakest part

Heroically fashioned – to infuse

Faith in the whispers of the lonely Muse

While the whole world seems adverse to desert.Keats’ formulation of ‘Negative Capability’, the quality required for literary greatness, is among the clearest statements of the role which now falls to the artist, a figure who must be ‘capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’

* * *

I have been making a historical argument, though it is the argument of an intellectual vagabond who goes cross-country through other people’s fields. Since we are now coming to the height of the matter, let me take a moment to catch my breath – and recall an earlier attempt at covering this ground, made in the third chapter of the Dark Mountain manifesto:

Religion, that bag of myths and mysteries, birthplace of the theatre, was straightened out into a framework of universal laws and moral account-keeping. The dream visions of the Middle Ages became the nonsense stories of Victorian childhood.

The claim towards which I have been building here is that those elements which became increasingly marginalised within respectable religious and intellectual culture by the middle of the 18th century found refuge in art. In many times and places, and perhaps universally, the activity of art has been entangled with the sacred, with the rituals and deep stories of a culture, its cosmology, the meaning it finds or makes within the world – and all of this wound into the rhythms which structure our lives. What is new in the historical moment around which we have been circling is the sense that the sacred has passed into the custody of art: insomuch as it dwells with mystery, ambiguity and mythic thinking, it now fell to the artist to keep the candle alight. Here, I submit, is the source of the peculiar intensity with which the language of art and the figure of the artist is suddenly charged.

* * *

If art has carried the flame of the sacred through the cold landscapes of modernity, it has not done so without getting burned. The scars are too many to list here, but I want to touch on two areas of damage.

First, the roles assumed by artists over the past two centuries have overlapped with those which might in another time or place have been the preserve of a priest or prophet. In a culture capable of elevating an artist to the status of ‘super-being’, there is a danger here: the framework of religion may remind adherents that the priest is only an intermediary between the human and the divine, but there are no such checks in the backstage VIP area. The danger is that the show ends up running off the battery of the ego instead of plugging in to the metaphysical mains. Even when an artist sees her role as a receiver tuned into something larger than herself, without a common language in which to speak of the sacred, the result may be esoteric to an isolating degree. How much of the self-destruction which becomes normalised – often romanticised – as part of the artistic life can be traced to the lack of a stabilising framework for making sense of the mysteries of creative existence?

Another danger arises from the exceptional status of the artist. While the reality of artistic life is often precarious, there exists nonetheless a certain exemption from the logic which governs the lives of others: the artist is the one kind of grown-up who can move through the world without having to explain their rationale, whether monetary, vocational or otherwise. In theory, at least, if you can get away with calling yourself an artist, you will never be required to demonstrate the usefulness, efficiency or productivity of your labours. Where public funding for the arts exists, if you can prove your eligibility, you may even join the privileged caste of those for whom this theory corresponds to reality. (And you may not: ‘performance targets’ for funded arts organisations can be punishingly unreal.)

The danger of the artistic exception is that it serves to reinforce the rule: get too comfortable with your special status as the holder of an artistic licence and you risk sounding at best unaware of your privilege, at worst an active collaborator in the grimness of working life for your non-artist peers. (Arguably, the only ethical model of artistic funding is a Universal Basic Income, which is how many young writers, artists and musicians approached the unemployment benefits system of the UK as recently as the 1980s.)

Begin Again

And here we are, back in the early 21st century, where the legacies of the Romantics and the Enlightenment are both persistent and threadbare. We don’t know how to think without them, and yet they seem out of credit, like a congregation that attends out of habit rather than conviction, or not at all.

A few years back, there was a fire at the Momart warehouse in east London. Among the dozens of artworks that went up in smoke were Tracey Emin’s tent and the Chapman brothers’ Hell. John Carey has some fun setting the reactions of callers to radio phone-ins against all those high-flown statements about the spiritual value of art: ‘Only in a culture where the art-world had been wholly discredited could the destruction of artworks elicit such rejoicing.’

Under these conditions, do I truly propose to lay a further weight on the shoulders of my artist friends – to charge them with the task of reconfiguring the sacred? Not quite.

If art gave refuge to the sacred and served as its most visible home in a time when it was otherwise scoured from public space, I believe the time has come for art to let it go. In the world we are headed into, it won’t be enough for an artist caste to be the custodians, the ones who help us see the world in terms that slip the net of measurable utility and exchange. One way or another, the ways of living which will be called for by the changes already underway include a recovery of the ability to value those aspects of reality which cannot be appropriated, which elude the direct gaze of reason, but which so colour our lives that we would not live without them.

This is not a call for a new religion, nor for a revival of anything quite like the religions with which some of us are still familiar. I have met the sacred in the stone poetry of cathedrals and the carved language of the King James Bible, but buildings and books never had a monopoly. For that matter, art was not the only place the sacred found shelter, nor even the most important – though it was the grandest of shelters and the one that commanded most respect, here in the broken heartlands of modernity. Out at the places we thought of as the edges, there were those who knew themselves to be at the centres of their worlds, and who never thought us as clever as we thought ourselves. Even after all the suffering, after all the destruction of languages and landscapes and creatures, there are those who have not given up. But if we whose inheritance includes the relics of Christianity, Enlightenment and Romanticism have anything to bring to the work that lies ahead, then I suspect that one of the places it will come from is the work of artists who are willing to walk away from the story of their own exceptionality.

And though I know that I am drawing simple patterns out of complex material, it seems to me that something like this has begun, at least in the corners of the world where I find myself. I don’t think it is an accident that several of the artists I have invoked here returned to work in the towns where they grew up; the pretensions you picked up in art school are not much use on the streets where people knew you as a child.

Unable to appeal to the authority of art, you begin again, with whatever skills you have gathered along the way and whatever help you can find. You do what it takes to make work that has a chance of coming alive in the spaces where we meet, to build those spaces in such a way that it is safe to bring more of ourselves. This does not need to be grand; you are not arranging a wedding. A group of strangers sits around a table and shares a meal. A visitor tells a story around a fire. You half-remember a line you heard as a child, something about it being enough when two or three are gathered together.

Published in Dark Mountain: Issue 12 ‘SANCTUM’, a special issue on the theme of ‘the sacred’.

-

You Want It Darker

As things stand, I don’t believe we will get a story worth hearing until we witness a culture broken open by its own consequence.

Martin Shaw, Dark Mountain: Issue 7The regular mechanisms of political narration are breaking down. The pollsters lose confidence in their methods, the pundits struggle to offer authoritative explanations for events that they laughed off as wild improbabilities only months before.

It’s a measure of how badly things have broken that, over the past year or two, members of the strange crew that meets around Dark Mountain have found ourselves filling the gap. I’m thinking of posts we’ve written in our various corners of the internet that were read and shared far more widely than most of us are used to, seemingly because they helped readers find their bearings in a time of deepening disorientation.

There’s a role for this kind of writing now that seems clearer than it did eight years ago, when we started this project. That’s why, today, we are launching a fundraising campaign – asking for your help to build and launch a new online publication. It won’t replace the Dark Mountain books, but it will run alongside them and provide an online home for writing that seeks – as my co-founder, Paul Kingsnorth put it at the start of this series – ‘to make sense of things, and to examine our stories in their proper perspective.’

At this point, if you want to head straight for our fundraising page and make a donation, then be my guest – but in the rest of this post, I want to make a few suggestions about why this kind of writing matters now, based on what Dark Mountain has taught me over the past eight years.

* * *

Let’s start with a few of the pieces I mentioned – the chances are you already read some of these, but setting them alongside one another, something else comes into view:

- First, here’s Anne Tagonist on ‘The Unnecessariat’, how America looks from an autopsy room in the middle of the epidemic of overdoses and suicides.

- There are a few posts I could pick from John Michael Greer’s Archdruid Report, but start with this on ‘Donald Trump and The Politics of Resentment’ (and note that it was written back in January 2016).

- Then, on the eve of the US election, there was Paul’s post on ‘The Revolutionary Moment’ – and later, kicking off this series of reflections on 2016, his ‘Year of the Serpent’.

- Also from this series, Charlotte Du Cann’s ‘The Reveal’: ‘When I switch off the machine and the headlines recede, I realise we are not in a political crisis; we are in a spiritual crisis, an existential crisis.’

- Which brings me to ‘A Counsel of Resistance and Delight in the Face of Fear’ from Martin Shaw.

- And finally, a couple of pieces of my own, both written into the raw aftermath of recent elections – first ‘The Only Way Is Down’, the morning after the UK general election of 2015 – and then ‘When the Maps Run Out’, a letter written in the days after Trump’s victory.

These are posts that got shared and reblogged and quoted and seemed to travel halfway around the internet. Mostly, they were written for our personal blogs or websites – but the authors are editors or regular contributors here at Dark Mountain. You can see places where we spark off each other’s ideas, as well as significant differences in perspective. If you read them all, you’ll probably find some that jive with you and others that jar. But I want to point to some common ground.

For one thing, while we draw on different political traditions, this is writing that starts a couple of steps back from the familiar terrain of political debate and analysis. I’m reminded of an answer I gave, years ago, when asked if Dark Mountain was a political project: ‘I think there may be times when it is necessary to withdraw from today’s politics, in order to do the thinking that could make it possible for there to be a politics the day after tomorrow.’ Or as Paul put it at the opening of this series, ‘Sometimes you have to go to the edges to get some perspective on the turmoil at the heart of things. Doing so is not an abnegation of public responsibility: it is a form of it.’

If you start exploring the work of any of these writers, you’ll find that mythology is a recurring reference point, a deep element in how we make sense of things. At the end of his post from the morning after the Brexit vote, Martin Shaw wrote, ‘Television, radio and internet will be able to tell you all the above-ground implications of what’s just taken place.’ When these surface accounts fail to satisfy, though, there’s a hunger that is fed by the underground currents of old stories.

One of the things that marks out this writing, then, is a willingness to enter territory that we could call ‘liminal’. It’s a term that comes from the study of ritual, given to the middle phase of a rite of passage: the preliminaries are over, you have shed the skin of an old reality, but not yet acquired the new skin that would allow you to return to the everyday world. The liminal is the space of the threshold, with all the vulnerability and potential of transition: the costliness of letting go, with no guarantee of what will come after. The liminal phase of a ritual is the moment of greatest danger – or rather, ritual is a safety apparatus built around the liminal. Whichever, the liminal is where the work gets done, where the change happens.

So here’s the first suggestion I want to make: if this writing is filling a gap left by the failure of more conventional kinds of political narration, it’s because it is able to operate in the territory of the liminal, and these are liminal times.

* * *

It’s not just the broadening audience for this writing that points to its timeliness. The past year also saw more conventional voices getting drawn into the territory that Dark Mountain has been exploring.

Take Alex Evans, a former advisor to the UK government and the United Nations, who just wrote a book called ‘The Myth Gap’. After a career based on belief in the power of ‘evidence, data and policy proposals’, his experience of global climate negotiations brought him to a crisis, and to a sense of the need for something more than facts and reasoned arguments. ‘We’ve lost the old stories that used to help us make sense of the world,’ he says, ‘but without coming up with new ones.’ And he quotes Jung: ‘The man who thinks he can live without a myth is like one uprooted, having no true link either with the past, or the ancestral life within him, or yet with contemporary society.’

Or check out the series on ‘spirituality and visionary politics’ that the political strategist Ronan Harrington edited for Open Democracy last year – and Jonathan Rowson’s report on spirituality for the RSA. ‘Scratch climate change confusion long enough,’ writes Rowson, ‘and you may find our denial of death underneath.’

There’s lots to say about these examples, but for now I just want to take a couple of points from them. First, that the call of the liminal is making itself felt ‘above ground’. But then, that there is a danger of wanting to jump straight to rebirth, to promise bright visions and new positive narratives. Evans draws on Jung, but I’m not clear how much room there is here for the shadow – nor for the loss and uncertainty, the darkness and disorientation that are the price for entering the liminal.

Then again, by the end of 2016, others were ready to make the descent. I once spent an hour on stage with George Monbiot pounding me over the pessimism of Dark Mountain, so it was striking to read his list of ‘The 13 impossible crises humanity now faces’. Then you had John Harris discovering Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies. Watching experienced journalistic commentators move in the terrain that Dark Mountain has been exploring for the best part of a decade, it strikes me that there is another danger. To navigate at these depths, you need a different kind of equipment. Facts alone don’t cut it down here.

This brings me to the other aspect of Dark Mountain which may be crucial to finding our bearings within the liminal – the centrality of art and culture to the work of this project.

* * *

A man is whispering in your ears, disorienting you, playing tricks with your perception, even as you watch him alone on stage with little more than a few bottles of water and a cast of microphones. This is Simon McBurney’s The Encounter, one of the most staggering pieces of theatre I witnessed in 2016: a show that leads you into the story of a meeting between a photographer lost in the Amazon and a tribe whose world is under threat. Their response to this threat takes the form of a ritual, a journey to ‘the beginning’, which is also a deliberate bringing to an end of their culture in its current form.

The concept of liminality was first used to describe the structure of rituals like the one at the centre of The Encounter, but its application as a term for thinking about modern societies is connected to the study of theatre and performance. The anthropologist who made the connection, Victor Turner, distinguished the ‘liminal’ experiences of tribal cultures – in which ritual is a collective process for navigating moments of change – from the ‘liminoid’ experiences available in modern societies, which resemble the liminal, but are choices we opt into as individuals, like a night out at the theatre. This distinction comes with a suggestion that true liminality, the collective entry into the liminal, is not available within a complex industrial society.

Now, perhaps this has been true – but here’s my next wild suggestion. The consequences of that very complex industrial society are now bringing us to a point where we get reacquainted with true liminality. To take seriously not just what Dark Mountain has been talking about, but what Monbiot and Harris are touching on, is to recognise that we now face a crisis which has no outside. The planetary scale of our predicament makes it as much a collective experience as anything faced by the tribal cultures studied by Turner and his colleagues.

If this is the case, then where within our existing cultures do we go for knowledge about how to navigate the terrain of liminality? Not to the sources of factual authority, much as we need them, but to the places where liminoid practices have endured – to the arts, especially those forms in which people gather and share a live experience, and also (Turner would tell us) to those traditions and institutions that deal with the sacred.

In 2016, I came to the end of two years working as leader of artistic development with Riksteatern, Sweden’s touring national theatre. The collaboration came about because their artistic director had been strongly influenced by the Dark Mountain manifesto. In the workshops we ran together, writers, directors and performers met around the question of what art can do, in the face of all that we know and fear about the depth of the mess the world is in.

The answers that emerged began with a rejection of the usual invitation to put our art to use as a communications tool to deliver a message on behalf of scientists, policy-makers or activists – not out of some misplaced sense of ‘art for art’s sake’ purity, but because this isn’t how art works.

Instead, many of the possibilities I caught sight of during this work had to do with the liminal. Art can hold a space in which we move from the arm’s-length knowledge of facts, figures and projections, to the kind of knowledge that we let inside us, taking the risk that it may change us. Art can give us just enough beauty to stay with the darkness, rather than flee or shut down. Like the bronze shield given to Perseus by Athena, art and its indirect ways of knowing can allow us to approach realities which, if looked at directly, turn something inside us to stone. Art can call us back from strategic calculations about which message will play best with which target group, insisting on the tricky need for honesty – there’s a line I kept coming back to, from the playwright Mark Ravenhill, that your responsibility when you walk on stage is to be ‘the most truthful person in the room’. Art can teach us to live with uncertainty, to let go of our dreams of control. And art can hold open a space of ambiguity, refusing the binary choices with which we are often presented – not least, the choice between forced optimism and simple despair.

These are strange answers. For anyone in search of solutions, they will sound unsatisfying. But I don’t think it’s possible to endure the knowledge of the crises we face, unless you are able to draw on this other kind of knowledge and practice, whether you find it in art or religion or any other domain in which people have taken the liminal seriously, generation after generation. Because the role of ritual is not just to get you into the liminal, but to give you a chance of finding your way back.

Among the messages of the liminal is that endings are also beginnings, that sometimes we need to ‘give up’, that despair is not a thing to be avoided at all costs – nor a thing to be mistaken for an end state.

* * *

Somewhere in the tumbling days that followed the US election, I saw it go by in the stream of social media. ‘It’s basically Breitbart vs Dark Mountain now, isn’t it?’ someone wrote, like we’re the last ones left whose worldviews aren’t in smithereens after the year that just happened. And like a few things in 2016, it had the taste of a bad joke that might have more truth in it than you’d want to be the case.

In the last weeks of the year, as we were putting together this series of reflections, a discussion got started among the Dark Mountain editors about what the role of this project should be, in the years ahead. Bad jokes aside, it’s clear that the work we’ve been doing has taken on a new relevance, and with that comes a sense of responsibility.

A couple of things are clear. The books we publish will always be at the heart of this project – and the work of artists, the makers of culture, will always be our starting point.

Every year, thousands of copies of our books go out to readers around the world. By the standards of an independent literary journal, it’s an achievement, and it’s through the sale of our books that we’re able to pay for some of the work that goes into Dark Mountain. (The rest of the work, as you can imagine, is a labour of love.)

A sobering realisation this autumn, though, was that the audience coming to this website each year is a hundred times the size of the number of people ordering the books. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course – but over the years, we’ve given only a fraction of the attention to this site that goes into each of our print issues.

So we came to the conclusion that it’s time to do something online that comes closer to the richness of the books we publish (and will go on publishing). Exactly what form this takes, we’re still working on – but it’s going to be an online publication, something more and different to a blog – and a site that reflects more of the web of activity of the writers, thinkers, artists, musicians, makers and doers who have taken up the challenges of the Dark Mountain manifesto.

To make this happen, we need your help.

We’re asking for donations to cover the costs of building and launching a new online home for Dark Mountain. You can send a one-off amount, or set up a small monthly subscription – or if you’d like to talk about other forms of support, then you can get in touch. Everything you need to know is here, on our new fundraising campaign page.

How ambitious we can be with the next phase of Dark Mountain depends on the level of support we get, so at this stage we’re not setting a fundraising target or a deadline – but we’ll tell you more as we go along.

Meanwhile, thank you for reading and sharing the work we publish. From the crowdfunding of the manifesto onwards, everything Dark Mountain has done over the years has been made possible by the support of friends, collaborators and readers. We don’t take that for granted – and wherever things go next, however dark it gets, we’re thankful for the journey we’ve been on with you.

Published on the Dark Mountain website as the closing essay in a series reflecting on the political events of 2016 — and to launch the campaign that crowdfunded the new online edition of Dark Mountain. Over the following six months, we succeeded in raising over £37,000 to fund the creation of a new online edition which launched in June 2018.

-

A Farewell to Uncivilisation

The skies opened and all the waters in them fell at once. It was a rain so hard I remember the weight of it on my shoulders, so loud you had to shout to have a chance of being heard. Yet, uncommonly for England in summer, it was not a miserable rain. There was something triumphant about it.

Perhaps because we all knew we would soon be in vehicles, heading back to the sheltered lives we had come from. Perhaps because we had already endured a weekend of hard showers, woodland mists and other watery intrusions. But also because it felt somehow like a seal of approval, a full-throated elemental roar in answer to the voices raised here in the past three days, the past four years, at the last moment of the fourth and last Uncivilisation festival.

Insist too hard on the significance of a poetic coincidence and you will make people uncomfortable. Better to recount such moments as jokes the world seemed to join in with than as some kind of revelation, but my experience of those four festivals includes several of them. The first came that first year, before we had found the site in the Meon valley that became our home, when several hundred people gathered in Llangollen, unsure what to expect. The landscape was darker, wild and splendid, but the venue itself was a converted sports hall. We had never organised anything like this, and our hosts were used to organising comedy nights and concerts for local audiences who bought their tickets, sat in their seats, enjoyed the show, applauded and went home. We were unprepared for the logistics of a festival and unprepared for the ways in which a festival comes alive. There were a hundred things wrong: plastic beer in plastic cups, a campsite too long a walk from the venue, a main hall where rows of seats faced a stage where speakers could barely see for the dazzle of the theatre lighting. Yet somehow, in spite of it all, this became a place where magic could happen.

The moment it happened for me, that year, was on the Sunday, as Jay Griffiths spoke about the shapeshifting power of language only for gremlins to take hold of the sound system so completely that the technicians could barely coax a murmur from it. After a couple of minutes of confusion, the room reassembled, people sitting in circles around Jay on the stage and on the floor. And there, the spell was broken, the face-off between speakers and spoken-to giving way to a shape as old as stories.

From there on in, the memories seem to dance with each other, as we found ways to open the circle and let others step in, until I am not sure which of the things I remember happened to me and which I only heard about. The wild figures in the fields, on the edge of sight. The late night tellings that bewitched us around the fire. The daylight stories of loss and pride, still fresh and urgent on the tellers’ faces. The music that picked up at the place where words ran out. The rhythm of rain on the roof of a marquee. Thirty people penned inside a square of rope to reenact the memory of a Russian prison cell. The sharpening of a scythe. Laughter and fooling and horns and antlers. At the end of everything, a singer’s voice going up into the night.

Someone said, one Sunday morning, almost embarrassed, that this was the closest thing they had to going to church. All along, it was there, the awkward presence of something no other language seemed fit for, the wariness of a language that so easily turns to dust on the tongue. Here is one way that I have explained it to myself. A taboo, in the full sense, is something other than a reasonable modern legal prohibition: it is a thing forbidden because it is sacred and it may, under appropriately sacred circumstances, be permitted, even required. Now, the space that we opened together, as participants, was a space in which certain taboos had been lifted: some that are strong in the kinds of society we have grown up in, some that have been stronger still in the kinds of movement many of us have been active in. Not the obvious taboos on physical gratification—most of what they covered is now not prohibited so much as required, in this postmodern economy of desire—but the taboo on darknesses and doubts, on naming our losses, failures, fears, uncertainties and exhaustions. In response to our earliest attempts to articulate what Dark Mountain might be, people we knew—good, dedicated people—would tell us, ‘OK, so you’ve burned out. It happens. But there’s no need to do it in public and encourage others to give up.’ Instead, it seemed, one should find a quiet place to be alone with the disillusionment. Perhaps become an aromatherapist. If I have any clue where the power of Dark Mountain came from—knowing that it came from somewhere other than the two of us who wrote the manifesto—then I would say it came from creating a space in which our darknesses can be spoken to each other. (From here, among much else, we may begin to question why the movements we have been involved in seem accustomed to use people as a kind of fuel.) By the second or third year of the festival, though, I found myself wondering if the sacred nature of taboo might not work both ways. If a group of people creates a space in which taboos are lifted, perhaps this in itself is enough to invoke the forms of experience for which the language of the sacred has often been used?

That is how I have explained it to myself, at least, for now; and if there is any truth in such an explanation, then it bears also on the role of those who take responsibility for creating such a space. We did not know, when we agreed—rather lightly—to that original invitation to host a weekend in Llangollen, that what we were creating was nothing so safe as a programme of talks, workshops and performances. Those elements were there, but they leave out much of what mattered most to those to whom the festival came to matter. The other, harder to name elements, which seem to have something to do with the sacred, call for another order of responsibility. The hard thing is not to create a space in which taboos can be broken, but to do it without people getting broken.

I have been reading stories from the 1960s, counterculture stories, uncomfortable reading, because there are things I want to understand better about the much-mythologised moment in which all that took place. There are plenty of broken taboos in those stories, and no end of broken people. By comparison, we were weekend amateurs, going nowhere near so high or so hard or so fast, but someone who had been through those years and lived to tell the tales told me this festival was the closest he had known to a reawakening of what he knew back then. If so, then here is confirmation that the taboos in which there is power today are of a different kind, for there is more hedonistic excess on a Saturday night in any high street in England than there was in four years of our Uncivilisation.

In the end, I think we learned to carry the responsibility, to hold this kind of space with care, though it took the wisdom of others who joined us at the heart of the festival-making. Nothing in the process of writing prepares you for such work, for a writer’s responsibilities are as bounded as the binding of a book, and the space from which writing comes is a solitary one.

We didn’t set out to start a festival, a festival happened to us. From those who came to it, we learned more about what Dark Mountain might be and what it might mean than we could ever have done at our desks. It felt good to have created it—and it feels good now to have brought it to an end. After all, there are reasons why no one tries to start a publishing operation and an annual festival as part of the same small new non-profit business in the same year. Somehow, we got away with it, although the price was paid in the fraying of our wits, and also in the inevitable carelessnesses—most of them small, but none of them unimportant—that happen when you are always trying to do too much at once. There are also reasons why a journal which is increasingly international, and not exactly enthusiastic about air travel, might not want to spend half its year organising a single event in the south of England.

For the next while, then, we are going to concentrate on doing one thing and doing it with the care it deserves, the thing we thought we were doing in the first place: bringing together books like the one you hold in your hands. We brought Uncivilisation to an end while it still felt like a joy rather than a duty. But the sparks from all those late night campfires carried further and there are friends of Dark Mountain organising events in the Scottish lowlands, the former coalfields of South Yorkshire and no doubt other corners of the world.

When the horns had sounded and the thank you’s and goodbye’s had been shouted through the downpour, a circle of friends sat for a few minutes in the shelter of a yurt. We sat quietly, the silence broken after a few moments, as one after another spoke about what he or she had taken from being part of Uncivilisation. Few of us had met before that first gathering in Llangollen and our stories echoed something I have heard over and over, from people who came every year and from people who came only once. A feeling of being less alone. For all the intensity of the mountain-top moments, what stays with us, what carries us through life, is this, the quiet magic of friendship.

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 5.

-

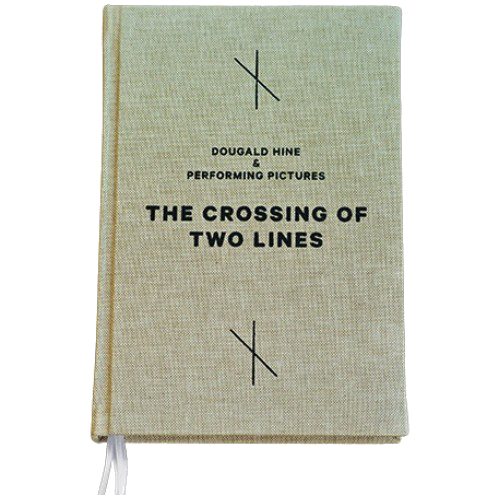

The Crossing of Two Lines

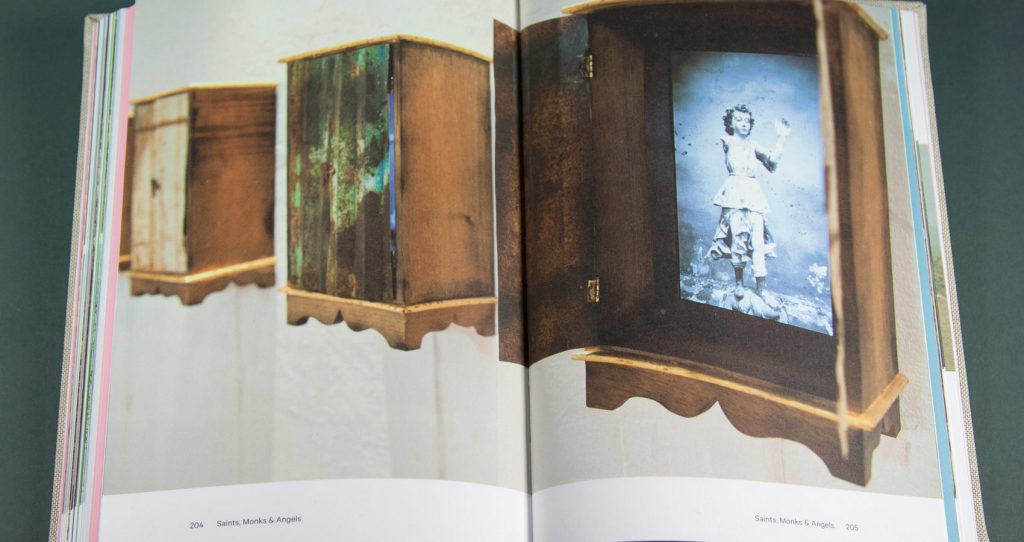

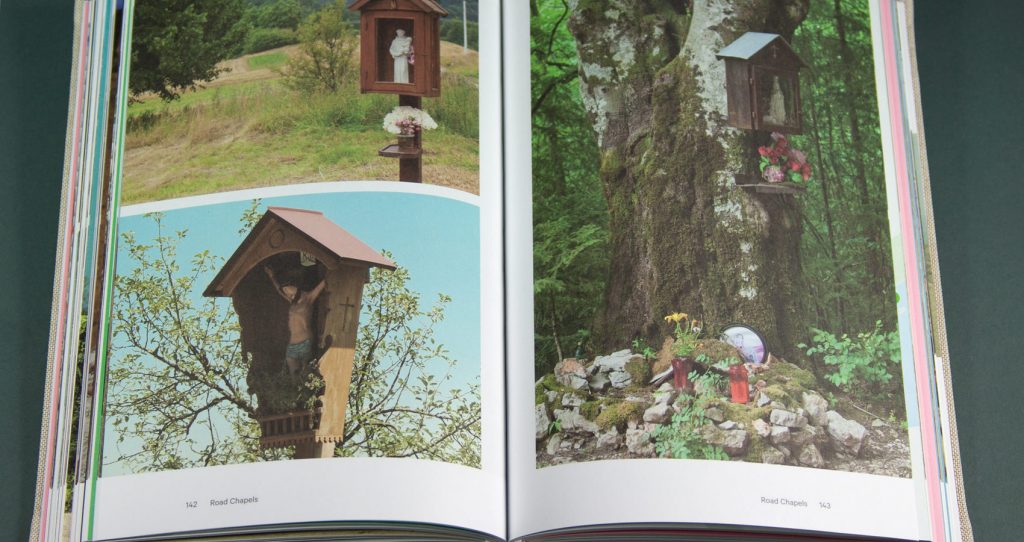

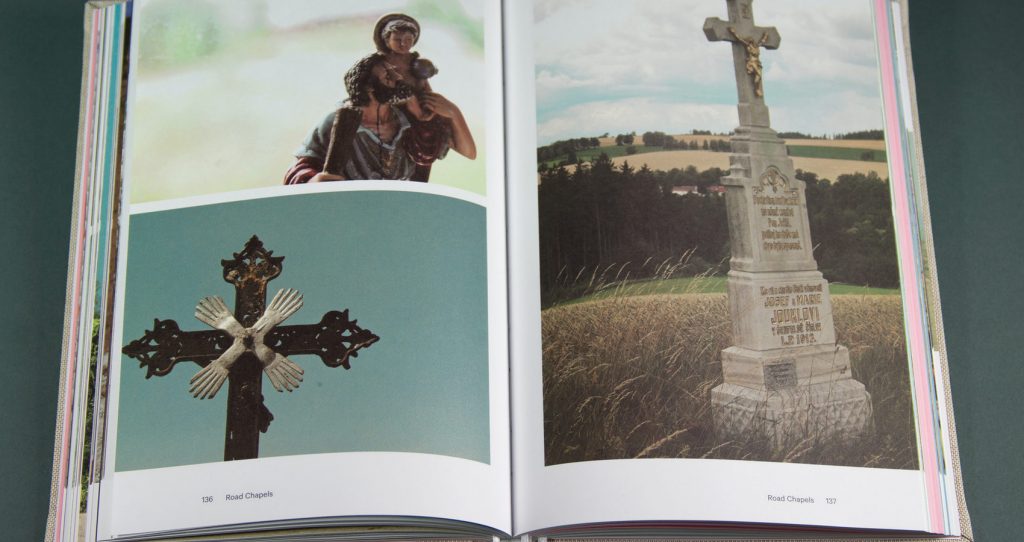

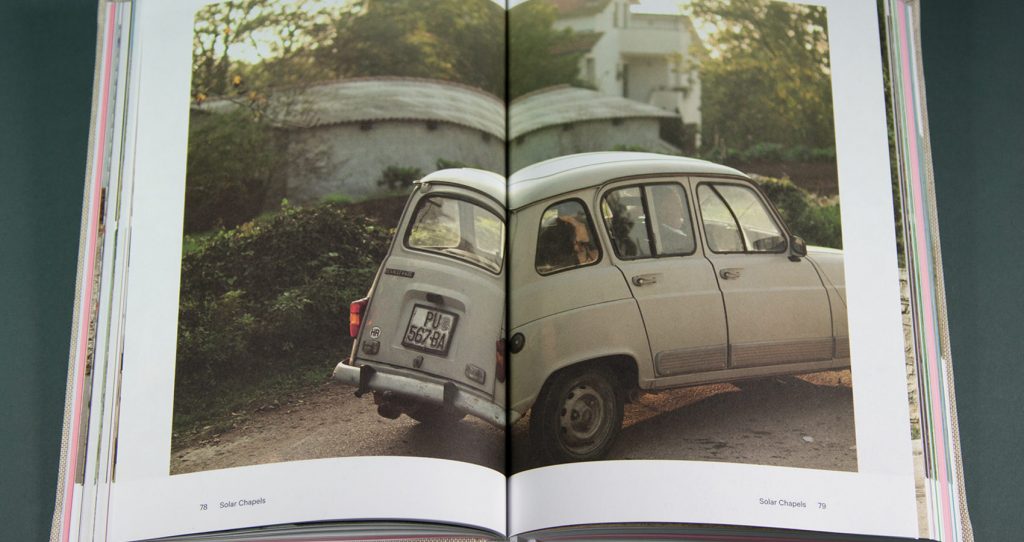

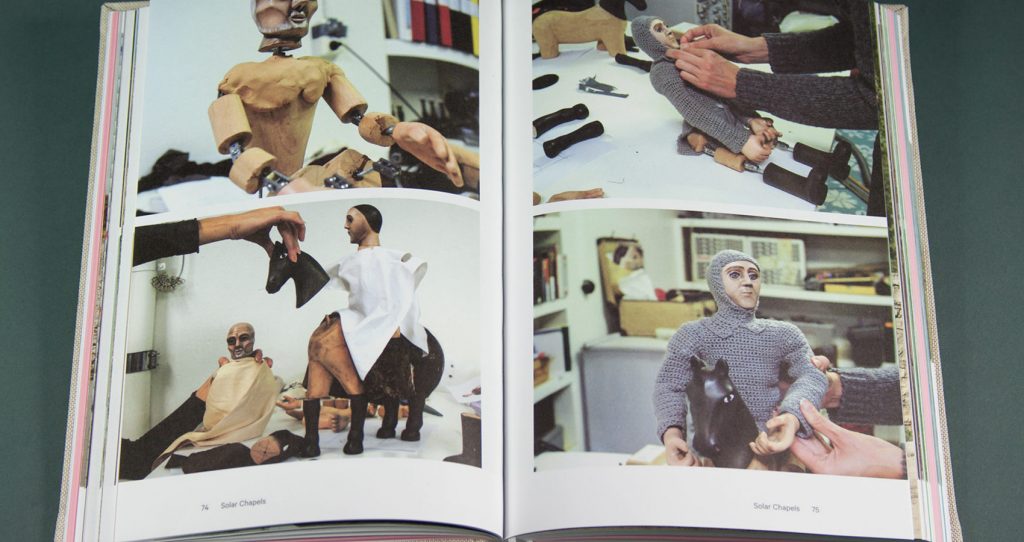

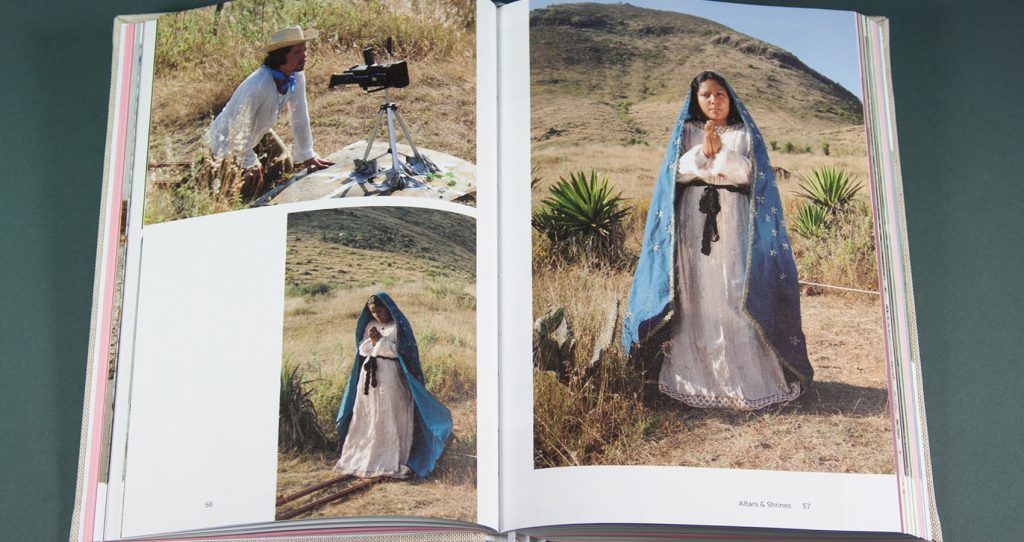

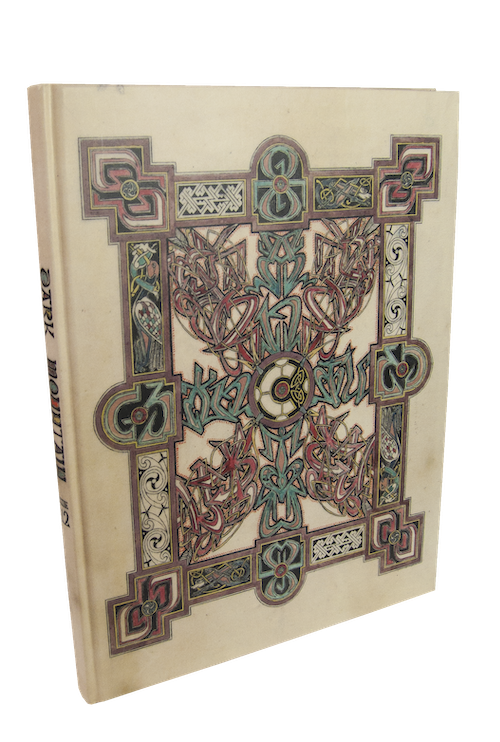

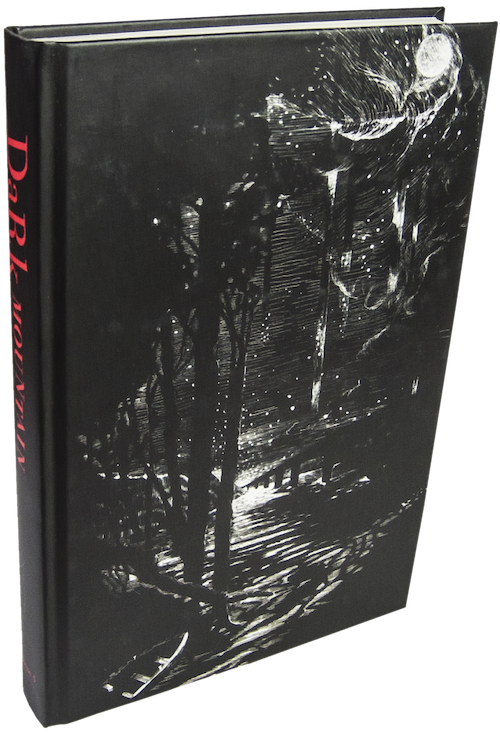

The Virgin of Guadalupe appears before a camera crew on a Mexican hillside. A wooden shrine is hammered to a watchtower on a deserted Soviet army base. A stonemason fixes a cross to the roof of a roadside chapel in his family’s village. Since 2008, the work of Stockholm-based artist duo Performing Pictures has taken an unexpected turn towards themes of Catholic devotion. The results are still sometimes shown in galleries, but their primary function is within the religious lives of the communities with whom they are made.

Sometimes we use the term religious art or sacred art, but I really prefer venerative art. Because, as I see it, the upper middle class, the good-taste people, they do venerate like hell!

Robert BrečevićThe book I made with Robert and Geska Brečević (aka Performing Pictures) is a document of this work, but also an enquiry into where it came from and the reactions it was causing among their artistic peers.

We are used to art that employs the symbols of religion in ways seemingly intended to unsettle or provoke many of those to whom these symbols matter; yet to the consumers of contemporary art, those who actually visit galleries, it is more uncomfortable to be confronted with work in which such symbols are used without the frame of provocation.

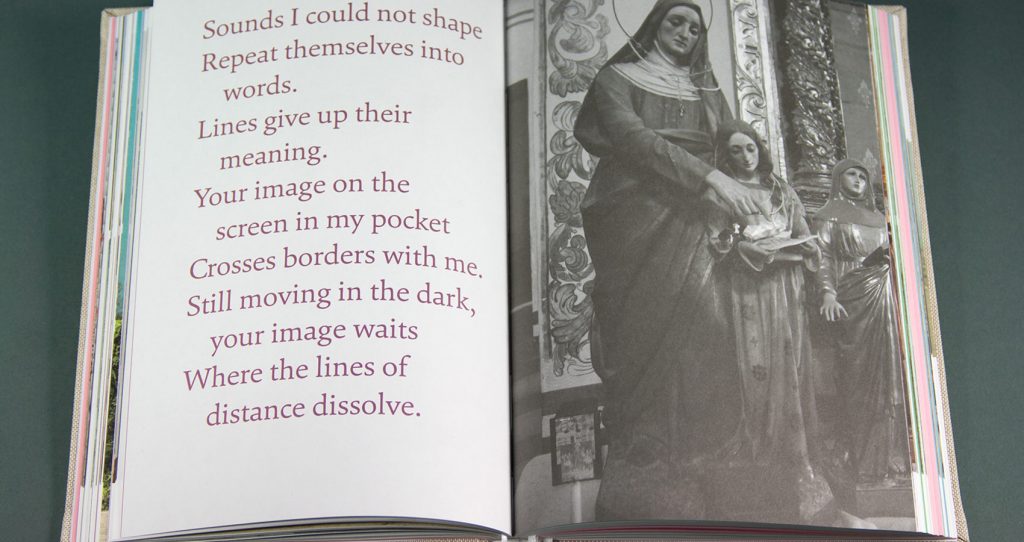

Alongside the hundreds of photographs documenting the making of this work, my contribution is one essay, four conversations with Robert and Geska, and a set of twelve poems.

-

The Crossing of Two Lines

The walls of the house on the Antešić land at Rab were built in the last years of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, but three generations would go by, and two wars, before it came to have a roof. They were a metre thick, those walls, made of local stone, the openings in places no architect would think to put them. It was the brothers Stjepan and Mile Antešić who began the building. On the island, the family grew olives and grapes, but what paid for the construction was the money Stjepan sent back from his work as a ship’s captain on the Danube.

War came and the building stopped. Stjepan joined the Partisans, fought against the occupying forces and the homebred Catholic fascism of the Ustaša, a stand that lived on in the lifelong anti-clericalism of his daughter, Dorica. It was her daughter, Milica, who married Alojz Brečević, a ship’s mechanic. They had met in Sweden, as migrant workers, and they started a family there, a family that would travel back each summer to help with the wine-making. Don’t get too used to this country, they told their son, each autumn: one of these years, we are going back for good.

That promise was severed by the new war of the 1990s and it was not until 1997 that Robert Brečević returned, alone, on a bus from Munich. Later, he and his wife, Geska, would come to visit the family land at Rab and — together with his stonemason cousin, Đani — take on the task of finishing what Stjepan and Mile had begun a lifetime earlier.

A black oak tree hides the stone house from the road. What can be seen is the small chapel, built the same year that the roof went on the house. In the evening, visitors come from around the island — families, old people, young couples out for a walk—to peek through the keyhole and, as if at a fairground peepshow, catch a glimpse of the moving figure of St Christopher carrying the child who will turn out to be Christ. The patron saint of the town of Rab, but also the protector of travellers, his presence is, among other things, a reminder of the journeys that went into the building of this house.

* * *

‘So when did Robert convert?’

The question came from a mutual friend who had heard that I was writing about the turn in the work of Performing Pictures that led to the projects documented in this book. More often, such questions are left politely unspoken, but they hang in the gallery air when this work is shown.

We are used to art that employs the symbols of religion in ways seemingly intended to unsettle or provoke many of those to whom these symbols matter; yet to the consumers of contemporary art, those who actually visit galleries, it is more uncomfortable to be confronted with work in which such symbols are used without the frame of provocation. The viewer hesitates between two anxieties: is there something here that I am missing — an irony, a political message, a joke — or is this a piece of propaganda on behalf of the believers? (Whatever they may believe, the evening visitors to the chapel at Rab show no sign of such anxieties.)

The turn is striking, certainly. There is nothing in the work of Performing Pictures prior to 2009 that would lead the viewer to expect the saints and shrines and altars we find here. The story behind such a turn deserves exploration. Yet if we want to trace the routes that led to this work, I suggest that the question of personal belief will prove misleading: it will not bring us closer to an understanding of what took place, and it may lead us to overlook those clues that have been left along the way.

* * *

Geska Helena Andersson was born into a family of small farmers in Skåne, the southernmost region of Sweden. Her parents’ life was anchored to the land — she was thirty before they had a holiday together — though the family had been migrant workers, too, in times when the farm alone could not support them. Her grandmother cycled half the length of Sweden, in those times, picking crops.