The Small Paths of Ivan Illich

On the map of the thinkers and writers whose influence formed me, a special place belongs to Ivan Illich (1926-2002). Quite simply, I don’t know who I would be, if I hadn’t met his work in my mid-twenties and then come into conversation with his surviving friends and collaborators. This page is the beginning of a gathering of materials in honour of his influence.

The Illich Canon

I want to cultivate the capacity for second thoughts, by which I mean the stance and competence that makes it feasible to inquire into the obvious. This is what I call learning.

— ‘Introduction to Askesis’, 1989

People often ask me where to start with Illich’s work. The answer will depend on where you are coming from, but the following summary is intended to provide some orientation. If you’re still unsure where to start once you’ve read this, then the first of the two books of conversations with David Cayley, Ivan Illich in Conversation, can be a good route into his work. (Another approach is to follow the traces of his thinking through the works of the many friends and co-conspirators whose books read like the other end of a conversation with Illich; when I have time to revisit this page, I will add a section providing leads for such an exploration.)

Pamphlets & Priesthood

The period of Illich’s greatest fame ran from the late 1960s through to around the end of the 1970s. This was accompanied by the books he would later call his ‘pamphlets’: Deschooling Society (1971), Tools for Conviviality (1973), Energy & Equity (1973) and Medical Nemesis/Limits to Medicine (1974/1976). These were written fast, fuelled by the conversations which took place at the Centre for Intercultural Documentation in Cuernavaca, Mexico. The latter two books were published in the Ideas in Progress series which Illich created with his London publisher, Marion Boyars, where first drafts were put straight into print and sometimes later redrafted and republished. Throughout the pamphlets, he is developing an analysis of the counterproductivity of the institutions of the industrial age.

Those interested in the roots of Illich’s thinking in his experiences as a Catholic priest will want to go back further, into the essays, articles and talks collected in Celebration of Awareness: A Call for Institutional Revolution (1969) and The Church, Change and Development (1970). These volumes are supplemented by The Powerless Church and Other Selected Writings, 1955-1985 (2018), the first volume in the Penn State Press series, Ivan Illich: Twenty-first Century Perspectives, which comes with an introduction from Giorgio Agamben.

The Historical Turn

In 1976, Illich and his friends took the decision to dissolve the centre in Cuernavaca, and from this point on, he lived an itinerant life, a guest in the homes of friends around the world. He would spend parts of the year as a visiting professor at universities including Penn State and the University of Bremen, but never had more than one foot inside an institution.

The Right to Useful Unemployment and Its Professional Enemies (1978) is a transitional text, published as ‘a postscript to my book, Tools for Conviviality‘. The same applies to the essays collected in Towards a History of Needs (1978), whose title suggests the direction of travel, as Illich’s focus moved from the critique of the institutions which monopolise industrial society to an intellectual archaeology of the buried assumptions which make industrial modernity thinkable.

This historical turn came to full fruit in Shadow Work (1981), the book of Illich’s to which I find myself returning most frequently. This was followed by the extraordinary and demanding Gender (1982), whose main text is accompanied by a set of lengthy footnotes which take the form of mini-essays, and H2O and the Waters of Forgetfulness: Reflections on the Historicity of “Stuff” (1985).

By the turn of the 1980s, Illich’s star had begun to wane. The interregnum of the previous decade had given way to the rise of neoliberalism, with the election of Thatcher and Reagan, bringing with it the individualist strain of the counterculture; in France, the left came to power and the constraints of government within a new world of globalised finance clipped its radical imagination; in America, the wave of environmentalism had peaked, while the Californian scene around the Whole Earth Catalog had fused with Silicon Valley and Stewart Brand was busy setting up his Global Business Network.

The final straw came with the reception of Gender: when Illich came to teach for a semester at UC Berkeley, the book was subject to what we would now call a cancellation by a group of influential American feminist scholars. The tragedy of this was that Illich’s work on gender was greatly influenced and enlivened by his friendship with a rather different group of feminist scholars in Germany, above all, the historian Barbara Duden, who became a longstanding friend and collaborator. However, the clash of cultures and the sheer complexity of the argument Illich was developing led to his being read and attacked as a reactionary misogynist in the Californian milieu.

A Commitment to Friendship

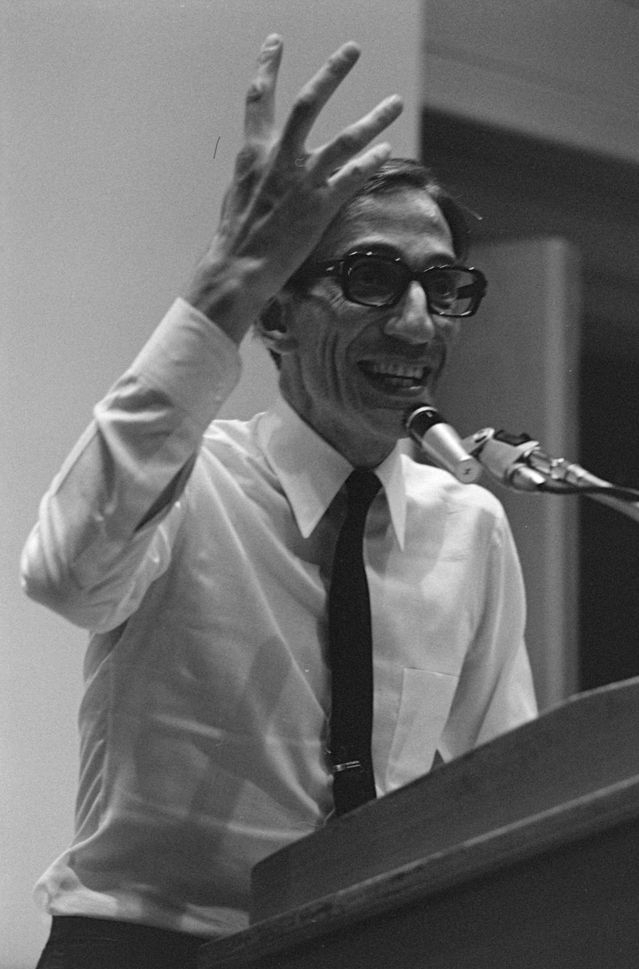

The events at Berkeley were painful – but more broadly, the end of the era of intense public attention seems to have given Illich a breathing room which he welcomed. He had spent much of the 1970s as a kind of human ‘jukebox’, he once joked, pumping out his greatest hits for audiences and interviewers. Now he eschewed the microphone and savoured the possibility of thinking grounded in particular friendships and settings. The pieces collected in In the Mirror of the Past: Lectures and Addresses, 1978–1990 (1991) reflect this: on each occasion, Illich is speaking the language and drawing on the frame of reference of a particular audience.

The four remaining books from this late period are all the fruit of particular friendships. ABC: The Alphabetization of the Popular Mind (1988), on the shift from orality to literacy in the European Middle Ages, was written in collaboration with Barry Sanders. In a different sense, In the Vineyard of the Text (1993) is also a collaboration with a friend: Hugh of St Victor, who died in the twelfth century. The book is a commentary on Hugh’s Didascalicon, and Illich uses the vantage point of the transformation of reading in the Middle Ages to see what is at stake in the late twentieth century shift from the book to the screen.

Then there are the two collaborations with the Canadian broadcaster David Cayley: Ivan Illich in Conversation (1992) and The Rivers North of the Future (2005). In each case, not without reservations, Illich allowed his friendship with Cayley to overcome his reluctance at being recorded. The first book begins with a biographical sketch, after which Cayley walks Illich through his own bibliography, as he offers reflections on each of his earlier books, their context and how he has come to see them in hindsight. In the second, posthumously published book, Cayley draws Illich into making a direct statement of his faith, but also a historical argument about the origins of modernity in the shadow side of Christianity.

Sources

Ivan Illich’s published works are now in print and available through the Sheffield-based publisher, Equinox, who curiously enough are based in the same building where I trained as a journalist in 2001-2.

An invaluable collection of Illich’s talks and essays is hosted by David Tinapple, including significant unpublished texts.

In addition to the two books of conversations, David Cayley has given us Ivan Illich: An Intellectual Journey (2021), not a biography exactly, but an in-depth intellectual study of Illich’s life and work. (A good deal of further material can be found on David’s blog.)

Two other biographical studies in English are worth noting. Divine Disobedience: Profiles in Catholic Radicalism (1970) by Francine du Plessix Gray includes her major New Yorker article, detailing Illich’s falling-out with the Catholic hierarchy in the late 1960s. More problematic is Todd Hartch’s study, The Prophet of Cuernavaca: Ivan Illich and the Crisis of the West (2015), which has a heavy axe to grind against its subject on behalf of the institutional church.

A major archive of Illich papers is held by Stiftung Convivial in Wiesbaden, Germany.

The Thinking With Ivan Illich website is one of the ongoing gathering points for friends of Illich and publishes a beautifully produced annual journal, Conspiratio.

L.M. Sacasas’s Substack, The Convivial Society, draws on Illich’s work and has introduced many new readers to it in recent years.

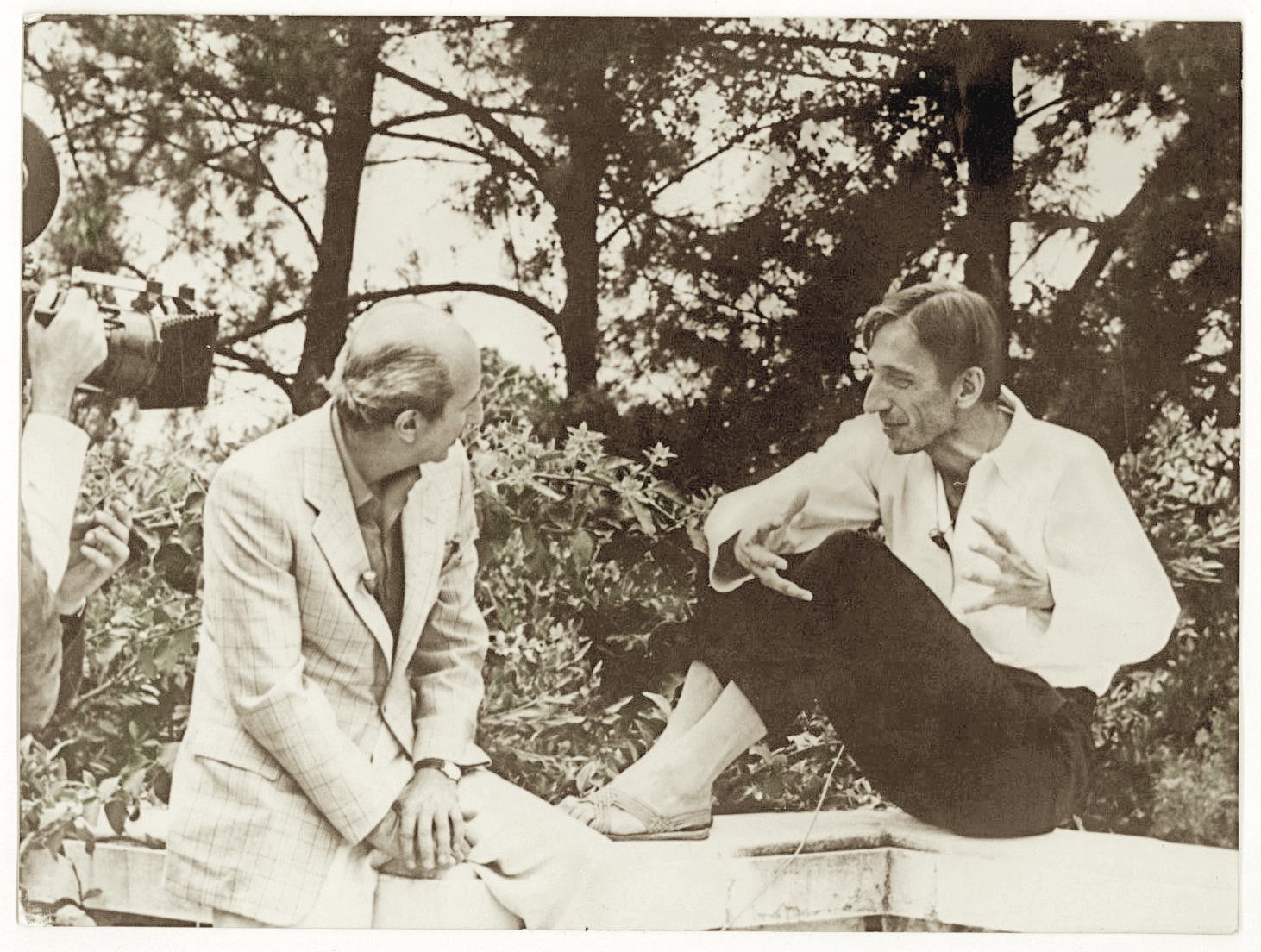

A young Illich

Braç, c. 1930

“Rulers had come and gone: the doges of Venice, the sultans of Istanbul, the corsairs of Almissa, the emperors of Austria, and the kings of Yugoslavia. But these many changes in the uniform and language of the governors had changed little in daily life during these 500 years. The very same olive-wood rafters still supported the roof of my grandfather’s house. Water was still gathered from the same stone slabs on the roof. The wine was pressed in the same vats, the fish caught from the same kind of boat, and the oil came from trees planted when Edo was in its youth.”

from ‘Silence is a Commons’ (Tokyo, 1982)

Branching Paths

A bibliography of Illich studies would be an enormous project. In what follows, I am only keeping note of some of the paths that I stumble upon during my ongoing journey with his work and its legacy.

Learning Without Education: Ivan Illich and the Sanctuary of Real Human Presence (University of Alberta, 2000), PhD thesis by Daniel Henry Bogert-O’Brien

Hermetic Alchemy as the Pattern for Schooling Seen by Ivan Illich in the Works of John Amos Comenius (Ohio State University, 1973), PhD thesis by William Ideson Johnson – how a conversation with Ernst Bloch in 1970 shifted Illich’s attention from ‘schooling’ as a problematic way of doing ‘education’ (the focus of Deschooling Society) onto the scrutiny of ‘education’ itself as a goal – includes transcripts from unpublished talks in which Illich discusses alchemy and the origins of education.

‘In Conversation with John Ohliger and Ivan Illich—April 8-10, 1978’, Jeff Zakarakis. Historical analysis of set of tape recordings made by Ohliger during a visit to Illich and Valentina Borremans in Cuernavaca.