We see things in the daylight, but in the night we have dreams and we process the things that we’ve seen and try to make sense of them, try to find a way of weaving them into our knowledge of ourselves and our ideas of ourselves in the world.

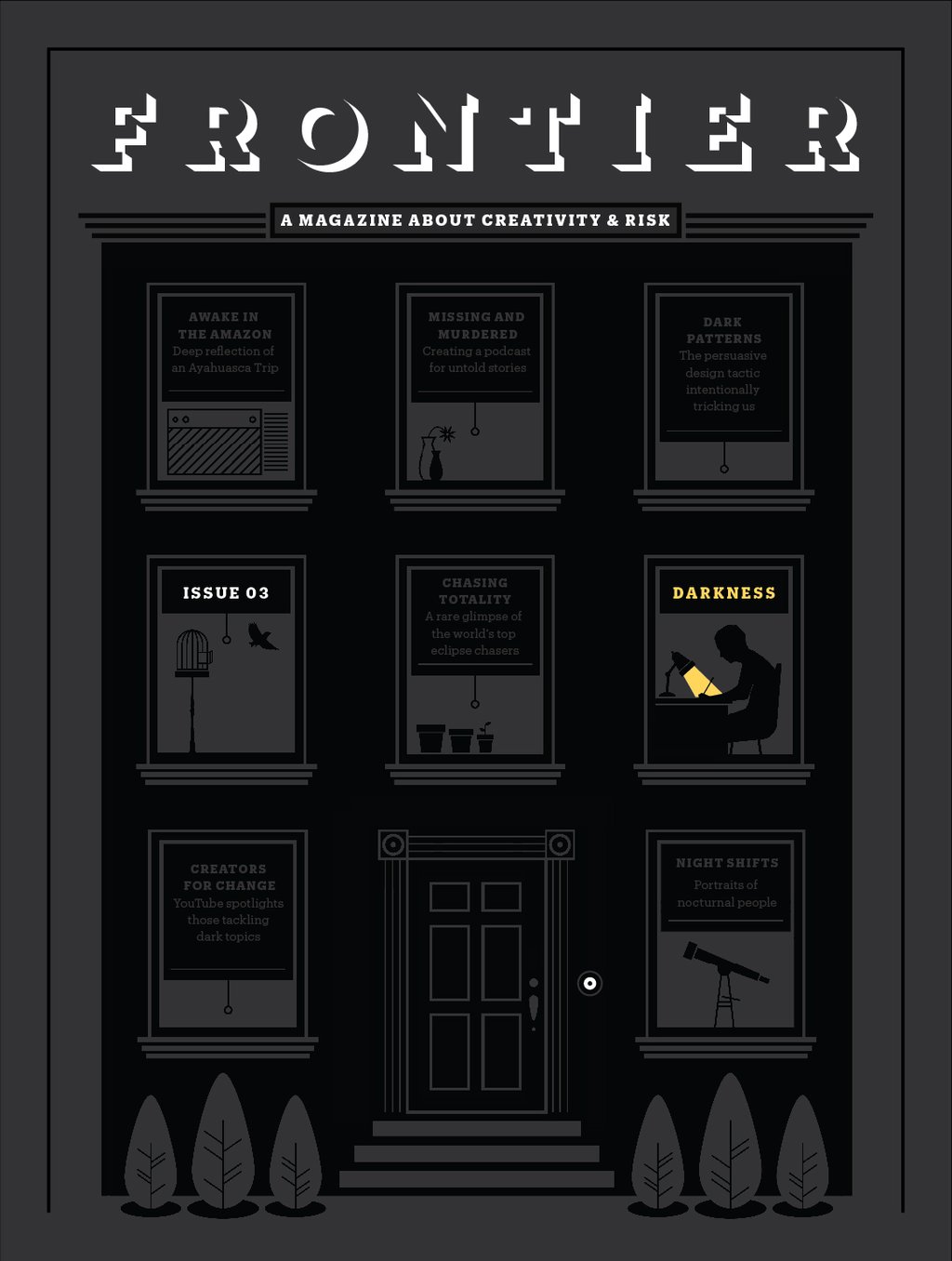

So this came in the post the other day, a very stylishly-produced publication from Canada called Frontier Magazine, with an article based on an interview I gave them last summer. The theme of the issue is Darkness and when Tristan Marantos talked to me over Skype last summer, he came with a set of questions that were unexpected, a change from the usual requests to tell the story of the Dark Mountain Project.

The result was one of the most enjoyable encounters I’ve had with a journalist in a long time. Here’s a bit of what I found myself saying:

When we talk about a thing like climate change, we don’t have languages for talking about fear and doubt and uncertainty. I’ve worked with scientists who are experts in the science of climate change but nothing within the training you have as a scientist equips you [for dealing] with what it does to you as a human being.

And so part of why Paul [Kingsnorth] and I ended up creating Dark Mountain has been about creating spaces where we can face the darkness and have ways of talking and thinking about the darkness of what it means to be alive right now…

I think that writers and artists have something to bring, in terms of showing us all that there are many languages. That the languages we choose to use, the symbols, the images are not simply obvious but are choices, ways of approaching a situation.

Certainly the place where the daylight expertise runs out can often be a place where the different elements of human experience can pick up, and provide the space within which we deal with the knowledge that comes to us in the daylight.

Elsewhere in the magazine, there’s a long, moving interview by Julian Brave NoiseCat with the CBC journalist Connie Walker about her podcast Missing and Murdered, and the role of the Indigenous storyteller in confronting the historical and ongoing crimes against women, girls and two-spirit people from First Nations communities. There’s also a photo essay, Wearing Black by Nick Kozak, about the Standing Rock protests. Apparently it’s stocked at one place in Stockholm – as well as various places across Canada – but if you want a copy, your best bet is probably to order it online.

Incidentally, I have a theory about why this interview stood out from the usual experience – and it has to do with the fact that the Frontier team aren’t journalists and editors all year round. They publish one issue a year and, in between times, the magazine mutates into a design agency, then back again, on an annual cycle. All of which makes me think of David Graeber and David Wengrow’s recent article, How to Change the Course of Human History (at least, the part that’s already happened), where they point out that for most of human (pre)history, we seem to have lived in cultures that underwent a seasonal oscillation between hierarchical and egalitarian forms of social organisation. Their argument is that the default mode of being human together involves an awareness of the arbitrariness of our social structures and an experimental approach to them, but that the story of what we usually think of as ‘civilisation’ might be better told as the story of how we got stuck in rigid, permanent, hierarchical forms of organisation. How much livelier would our work be if we had that kind of oscillation across the course of the year, instead of being stuck in one kind of role and organisation from year to year, the way most of us currently are?

Anyway, if I haven’t sent you off to read Graeber and Wengrow (and really, do read that piece), here’s the rest of the Frontier interview.