Author: Dougald Hine

-

After We Stop Pretending

The setting could so easily seduce you. Painted wooden houses line three sides of a square of grass: the red house, the white house and the low wooden barn between them where the bunk rooms are. On the fourth side, the slope falls away, past the village library, past the station house and the railway tracks to the lake. A strip of an island a hundred yards offshore, then miles of water stretching to a wooded horizon.

The first clue that something is wrong should be the colour of the grass: dead-yellow already in the first days of June. No rain for weeks. The radio says we had the hottest May in over 250 years, but seeing as the oldest continuous temperature records anywhere began in Stockholm in the 1750s, you can probably stick a few zeros on that figure.

Now look again at the island – the one in the photograph on the homepage for this school called HOME – and see how it changes when I tell you that the scatter of low buildings by the jetty is the oldest preserved oil refinery in the world, the soil still poisoned from spills before our grandparents were born. This is where we meet, in a landscape whose beauty is haunted by a history of extraction. Whatever else there may be to say, this is the background against which our voices rise and fall.

A train pulls into the platform. Among the passengers who disembark, there are a number wearing rucksacks, looking around to find their bearings. They take in the lake and the island and the hostel on the hill. Together, they begin the short climb that leads to where we are standing, and, with their arrival, something shifts: this school, which has so far been a story Anna and I are telling, becomes something larger, messier and more substantial. For the next few days, in these borrowed buildings, it will be a place where our ideas and fears and longings get tangled up with those of the people who have taken up our invitation, an invitation to ‘a gathering place and a learning community for those who are drawn to the work of re-growing a living culture.’

* * *

One member of the group that week stands out in my memory. Fran is not the loudest presence; a large, gentle man in his early forties, he can be humble almost to a fault, yet there is a steadiness that marks him out. Here’s what I think it is: out of the whole group, he is the only one who hasn’t come alone. I mean, he made the journey solo, sleeping on overnight coaches, but he was able to do this thanks to the support of dozens of people who chipped in to crowdfund his way to Sweden – and so he arrives with a small village at his back, a community to which he already had to explain what was calling him here, and by which he is held. Sometimes in the sessions, I can see their faces leaning in over his shoulder.

A few months later, I’m planning a trip to England when I get a message from Fran: would I like to come and visit his hometown and give a talk? So that’s how the two of us end up sitting on this low stage in an arts space in Stroud, along with our hosts, Emily and Ali; the four of us watching as the seats fill up and the queue stretches out the door, hoping we don’t end up having to turn people away. Looking out at this crowd, I’m guessing a good few of Fran’s villagers are in the house tonight.

Well, it seems the folks without seats are happy to stand at the bar, and the whole room listens intently over the next two hours as we talk about what it might mean to take seriously the question with which the invitation to our school began: ‘What if the culture you grew up in was broken in ways that you didn’t even have words for?’ I talk about things I’ve learned over the past decade with Dark Mountain: about how despair is not a thing to be avoided at all costs, nor an end state; about how much of what makes human existence endurable lies beyond the reach of the state and the market, unmarked on the maps we’ve inherited from recent generations; about the role that art has played as a refuge for those aspects of reality that retreat from the gaze of those who would measure and price everything, that slip away like deer into the forest; about the hunch that, whatever hope is worth having today, it lies on the far side of despair, where the maps run out, at the margins or hidden in plain sight.

Fran and I talk about what it means to make room for this within the ordinary fabric of our lives, among the everyday pressures; creating pockets, spaces to which it is safe to bring more of ourselves than it would be wise to bring to many of the workplaces, educational institutions or families we have known.

Then right at the end of the night, just as Emily and Ali are drawing things to a close, they invite a friend up to the stage, a woman I haven’t met yet.

‘A few of us are organising a rebellion,’ she says. Not words I was expecting to hear, but as she goes on, I realise that I’m listening to something new – or new to me, at least. This is the voice of an activism that comes from the far side of despair, that has room for grief, that calls for courage rather than hope, that frames the stakes of climate change as starkly as anything we’ve published in Dark Mountain: this is not about saving the planet by changing your lightbulbs, it’s not about how we can sustain the way of living of the Western middle classes or fulfil the promises of development or transition to eco-socialism; it’s about how many species will be driven out of existence in the decades ahead, and whether our own is to be among them.

Two weeks later, Extinction Rebellion delivers its demands to parliament, and as November goes on, their actions bring parts of London to a halt: blocking the five main bridges across the Thames, then holding up rush hour traffic at key junctions around the city, morning after morning. Even the organisers seem taken aback at the scale of the response. The other week, my mum called to say she’d heard a BBC radio documentary about Gail Bradbrook, and wasn’t that the woman I’d told her about from Stroud?

From the occasional Facebook messages we exchange, I get the sense that Gail and those around her are riding a storm now, so I’m glad we got that chance to meet briefly in the relative calm of the weeks beforehand. And it seems fitting that the thread of serendipity which brought us together should run back to the gentle presence of Fran and the weave of generosity that brought him to Sweden in the endless days of early June.

* * *

‘What do you do, after you stop pretending?’

I wrote those words one night in the spring of 2010, as we were preparing for the first Dark Mountain festival. They became the frame for the Saturday programme on the main stage, and when Paul and I wrote a comment piece for the Guardian ahead of the event, it ran under the headline: ‘The environmental movement needs to stop pretending’. Among the crowd who gathered in Llangollen that weekend, there were those who came expecting us to offer a vision of what the environmental movement should do instead, and they were disappointed. I remember one guy from Manchester who was outright furious, railing to anyone who would listen, writing to us afterwards to demand that we refund his ticket.

Maybe there are people whose ideas are born crystal clear and arrive in the world just as envisaged in the imagination, but my experience has always been that projects stumble into being: any new undertaking has to wrestle its way clumsily through the muddle of what you thought it would be, past the temptations of what others want it to be, until – if you’re lucky – it starts to reveal what it’s capable of being. In the case of Dark Mountain, it was only some years in that I saw clearly that this project wasn’t the place from which to ‘do’ anything. Whatever else, it has been a place where people come when they no longer know what to do; a place where you can bring your despair and put it into words, without being judged, without feeling alone, and without a rush to action or to answers.

There’s a subtlety here that’s not well served by the pugnacious rhetoric of some of what got written in the early days. Activist writing often has the tone of telling everyone else what to do, and that certainly carried over into the ways I used to word things. The subtlety is this: to insist that the space you are holding is not one from which plans can be made or action taken is not to claim that no one should be taking action or making plans.

There’s a video on YouTube, an hour and eight minutes in the quiet, slightly shambly company of Roger Hallam. It was filmed in a university lecture theatre last May, soon after the meeting at which Roger, Gail and a few others came up with the idea for Extinction Rebellion. If you sit down to watch it, make sure you have time to get to the end: I had to stop halfway and wait till the next morning, and this was a mistake.

The first 40 minutes are where he presents the climate science, attempting to add up how much warming is already inevitable and where this would take us. There is something mesmerising about the parade of numbers – 1.2° that has happened already; 0.5° within a decade from the loss of the Arctic sea ice; another 0.5° from CO2 already emitted but not yet fed through into warming; the water vapour effect, doubling the impact of warming from other sources to give another 1° – and this is just the start, he adds. Somewhere around the 3° mark, we’ll lose the Amazon – assuming Bolsonaro hasn’t got there first – and this will bring another 1.5° of warming. Having got this far, Earth will tip further into a hot state, outside the conditions under which humans are capable of living.

I’ve been reading, thinking, writing and speaking about this stuff for long enough to know that a certain caution is called for. As one climate scientist put it to me, the bits we know for sure are scary enough, without stating worst-case scenarios as facts. Still, watching the first half of Roger’s talk was enough to give me a sleepless night. Maybe we need those nights every so often, to be brought back to the existential core of our situation, to have the layers of reasoning with which we insulate ourselves peeled off.

‘Why we are heading for extinction,’ begins the title of the talk, ‘and what to do about it.’ The remaining half hour is the bit about doing. What is striking is that Roger makes no attempt to row back on the bleakness of what he has already told us. There is no bargain on offer here – ‘If everyone does X, then all this scary stuff will go away’ – only the observation, backed up by research on social movements, that those whose willingness to act endures the longest are not the activists who are motivated by outcome, who need to be given hope and to believe in their chances of success, but the ones who are motivated by doing the right thing. It’s the first time I can remember seeing a call to action which explicitly invites people to go into despair. In the closing minutes of his talk, Roger speaks about ‘the dark night of the soul’, the need to move through the darkness rather than avoid it. This is a call to rebellion that is framed in the language and draws on the traditions of mysticism.

I don’t say that this is without precedent; indeed, part of Roger’s argument is that the rational, secular logic of mainstream Western activism, with its dependence on promises of progress, is the anomaly, while the stance for which he speaks has more in common with what has sustained grassroots movements in other times and places, and continues to do so. But this is the first activism around climate change in the West that I’ve encountered that has roots this deep, that draws on spiritual traditions without slipping into New Age wishful thinking or fantasies about a collective evolution of consciousness. It’s the closest I’ve seen to an activism that can answer that question I didn’t know how to answer back in 2010: what do we do, after we stop pretending?

* * *

In late July, we hired a car and drove north. This was the middle of the wildfire season, the Swedish authorities were dropping bombs on burning forests and borrowing firefighting planes from Italy. Our county got off lightly, but there were nights when you could smell the smoke on the air. We’d be following a backroad between villages and a convoy of fire engines would come speeding past. Coming home one evening, on the radio, two young hipster comedians from Södermalm were sniggering about how stupid the countryside people are and why don’t they just move to Stockholm rather than live out in the sticks and wait for their houses to burn down – and I thought: what the fuck, does it not occur to them that the rest of the country might be listening?

We stayed on a farm and the farmer told us that she had a problem: in this heat, the lambs didn’t notice the shock from the electric fencing, so they were getting out and running everywhere. But her farm was lucky, she said, they had about three-quarters of the fodder they would normally have at this point in the year. In other parts of the country, farmers were trying to send their animals to slaughter because they couldn’t feed them, except the slaughterhouses couldn’t handle the number of animals the farmers wanted to send them.

At almost any moment in human history, this would be the highest-order crisis a human society could face: to have to slaughter your herds before summer is out because of a lack of fodder. For half a dozen generations now, we’ve lived in a world that is bound together by supply chains whose effect is to distribute the impact of any local crisis across the whole system, so that a failed harvest in the American wheat belt is more likely to cause bread riots on the streets of Cairo than on the streets of Chicago. This works until it doesn’t, until the frequency of local crises strains the global system to breaking point. In the meantime, while the system holds, it means that those whose ways of living place most strain upon the system will be the last to notice.

* * *

‘What you people call collapse means living in the same conditions as the people who grow your coffee.’

This was Vinay Gupta, on a Saturday afternoon in Llangollen in 2010, in the soulless converted sports hall of a venue where we held that first festival. It was one of those lines that everyone seemed to remember. There was talk of putting it on a t-shirt.

I realise now that I have taken consolation in such thoughts.

When Marks & Spencer put up those posters that said ‘Plan A: Because there is no Plan B’, I asked: no Plan B for who? For posh supermarkets and department stores, or for liveable human existence? Or do we no longer make the distinction?

When I wrote about Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, it was to point out the thread of irony running through it: you’ve got this kid and his father pushing a shopping trolley down a road. In one scene, the father finds what might be the last can of Coke in the world and presents it to his son like it’s a sacrament. Isn’t there something that gets missed here, among the biblical cadences and the apocalyptic horror: the traces of a satire on our inability to imagine a liveable existence beyond the bubble of supermarkets and superhighways?

Before Dark Mountain came on the horizon, I’d read my way through the writings of Ivan Illich, from the revolutionary moment of the early seventies, when he wanted to show that ‘two-thirds of mankind still can avoid passing through the industrial age’, to the late eighties, by which time he had seen environmentalism co-opted into the oxymoron of ‘sustainable development’. And still he was able to glimpse in the fiction of Doris Lessing, or the everyday realities of his friends in the barrios of Mexico City, ‘what kinds of interrelationship are possible in the rubble’, among the ‘people who feed on the waste of development, the spontaneous architects of a post-modern future.’

In talks, I would tell the story of the Natufians. Late in the last Ice Age, in the territory marked on our maps as Israel and Palestine, they lived in year-round villages. They were among the first people anywhere to settle and they lived like this for 1,500 years, fifty generations, long enough for any memory of their ancestors’ wanderings to pass into the dreamtime of gods and culture heroes. Then came the Younger Dryas, the 1,200-year cold snap that turned Europe back to tundra and broke the pattern of the seasons which watered the wooded valleys in which they had made their homes. They knew nothing of the processes by which this climate change had come upon them; it was not a consequence of their actions, only a shift in the weather. Within a short time, they abandoned their settled way of life and became wandering gatherers and hunters, returning to the old villages only to rebury the bones of their dead in the ruins of the houses.

Then I would recall a passage in After the Ice, Stephen Mithen’s history of the prehistoric world, where I first learned about the Natufians. He sends a time-traveller to walk unobserved through the lives of the people he is writing about: coming upon a band of late Natufian nomads, he follows them to a gathering in one of the ruined villages. The interment of bones is accompanied by storytelling, feasting and celebration; the connection between past and present is reaffirmed. In Mithen’s reconstruction, these days of festival offer a respite from the hardships of the present. Yet afterwards, as the people go back out onto the land, they do so gladly: ‘They are all grateful for the return to their transient lifestyle within the arid landscapes of the Mediterranean hills, the Jordan valley and beyond. It is, after all, the only lifestyle they have known and it is the one that they love.’

These stories were never meant as lullabies. We are living through a tragedy whose measure exceeds our comprehension and most of us are implicated in this tragedy. We were born into this situation and there is no simple way to free ourselves from it. The grand summits, the uplifting rhetoric of leaders, the protests at the summit gates: none of this will make it go away. The changes we make to our lifestyles, the meat we don’t eat, the flights we don’t take: none of this will be enough. We will not make this way of living sustainable, nor anything like this way of living – and yet, I’ve always felt able to add, this need not be the end of the story. There will almost certainly be creatures like us around for a good while to come, and though they will live with the consequences of the way we lived – though their lives may be hard, as a result, in ways we do not like to think about – they will not simply live in our shadow: the way of life of those who come after us will be, just like our own, the only lifestyle they have known and the one that they love.

I stop now, as I’m writing this, to take a swig of coffee, and I try to think about the lives of the people who grew the beans, the landscape in which they were grown. I try to think about the lives of the people who assembled the computer at which I type these words, the people who mined the minerals that went into its making, the places they were taken from the ground. The conditions in which the people who grow our coffee live are not simply a default, back to which you and I might tumble should the project of civilisation (or ‘development’, as it’s known nowadays) collapse. Our lives are more entangled than that, joined by global supply chains which stretch back into the unfinished history of colonialism and its plantations, where the lives of people and plants were subject to a brutal simplification.

Still, I have taken consolation in such thoughts, in the awareness that there are vastly more ways in which humans have made life work than the lifestyle which happens to prevail around here, just now. This way of living could unravel without that being the end of the story, the end of any story worth telling. I still hold this to be true, but lately I find there are more nights when I wonder whether anything will survive the unravelling.

* * *

Mid-October. Still tired from the two-day journey back from England, my first morning home, and I’ve agreed to record an interview for the Culture show on Swedish national radio. The presenter and I sit on a bench in the park across from the railway station. He starts off asking me about the fires this summer. He’s hoping I’ll say that something has shifted as a result, but all I can think of is the stream of comments, overheard at the hairdressers or the supermarket, or around my in-laws’ dinner table, through the rainless weeks of July and August. ‘Isn’t the weather amazing?’ people would say to each other, and ‘Don’t the farmers complain a lot!’ and ‘The government should really buy more of those planes so we don’t have to keep borrowing the ones from Italy.’

After the interview, I start to wonder, though. Perhaps something has begun to shift, below the surface: a change in the conversation about climate change in certain places, a darkening realism, a movement in the boundaries of what it is possible to talk about. I’ve had some strange encounters lately with people on the inside of institutions who have lost all faith in the usual stories about how we’re going to manage this mess we’re in.

That speech last September by Guterres, the UN Secretary General, was unusually stark: ‘I’ve asked you here to sound the alarm,’ he begins. ‘If we do not change course by 2020, we risk missing the point where we can avoid runaway climate change.’ Of course, in the next breath, he is insisting that there are great opportunities ahead for green economic growth, because anything else is still unthinkable. In quiet corners, though, I’ve heard the unease of people whose job it is to put together the numbers and show how all this can be done: the need to leave the assumption of growth unquestioned is pushing them into claims that are clearly absurd. Their question is how to voice the unthinkable in a way that will have a chance of getting heard.

Here’s what I think I’m picking up, as we head into 2019: the official narratives about climate change are under strain from so many directions, there may just be a major rupture coming. Another straw in the wind is Jem Bendell’s academic paper, ‘Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy’, released in August and downloaded over 100,000 times by the end of the year. From foreign correspondents to solarpunk hackers, I keep hearing how it’s reframed the discussions going on in all these different worlds. To many Dark Mountain readers, the message of the paper won’t come as a great surprise: ‘near-term social collapse’ due to climate change is inevitable, while catastrophe is probable and extinction possible. But when this suggestion is made by a professor of sustainability leadership with twenty years’ experience working with academia, NGOs and the UN, it has a different kind of impact, at once a symptom of the shift that is underway and a contribution to that shift.

Something similar applies to Extinction Rebellion. In its framing of the situation in which we find ourselves, in the energy which has gathered around it and the speed with which all this happened, it may well be among the first movements of a new phase in the story of our collision with the realities of climate change. If this reading of the signs is anywhere near right, then there will be other movements along soon, other kinds of rupture and other kinds of work to be done.

There’s an old video from Undercurrents, the activist film network, shot in 1998 at the Birmingham G7 summit. Thousands of Reclaim The Streets protesters gather outside New Street station. On an unseen signal, the crowd spills out into the road, whistling and whooping, swarming around buses and cars, outnumbering the yellow lines of police. In the chaos of the minutes that follow, a stretch of urban freeway is occupied; part of the concrete collar of ring road thrown around the city centre by modernist urban planners in the 1950s, it’s an appropriate site for a movement that has grown out of protests against the road-building plans of the current government.

A couple of tripods have gone up, the sound systems won’t be far behind – but right now, there’s aggro up at the front, where a few vehicles are still caught inside the reclaimed zone. A man just drove his car into a small group of protesters – not at any speed, just trying to nudge them out of the way, just threatening them with half a tonne of metal – and now he’s out of the car and arguing with the police, as more protesters put themselves in front of his car, holding a banner, and now the police are letting him get back in, and now he is putting his foot down and driving straight ahead, as everyone manages to leap aside, except for one young man who is still on the bonnet of the car as it accelerates beyond the last police lines and out onto an empty dual carriageway.

I’ve never managed to track down that video, though people have assured me it exists, but I was the guy on the car, and it was only luck that meant I walked away that day with nothing worse than bruises and shock. And while it was a drama at the time, I’d hardly thought of this in years, until I saw the livestreams of the swarming protests where lines of Extinction Rebellion activists were stopping traffic at major roundabouts in London, the queues of impatient motorists, the sound of car horns.

I learned two things the day I went for a ride on a Birmingham bonnet. The first was that I am not the person you want on the frontline, when tempers are fraying and the adrenalin is rushing. There must have been ten of us in front of that car when the driver put his foot down, and the other nine all managed to throw themselves clear. I love the ones who can keep cool and make good calls in the heat of the moment, but that’s not me, and my reflexes aren’t going to come to anyone’s rescue.

Compared to the days of Reclaim The Streets, Extinction Rebellion seems strikingly sober, yet there’s still a headiness to any movement as it gathers momentum. Watching from afar, as friends use their bodies to stop vehicles, I realise that I believe in the work that they are doing and I know that there are other kinds of work that will be needed, away from the frontlines. Among that other work, there’s still a need for the space Dark Mountain holds, not least as a place to retreat and re-ground, but it’s no longer my time to hold that space: I’ve known for a while, and it’s been official since October, that I’m moving on from this project. So that brings back the old question: what do you do?

The second thing I learned that day in Birmingham was more unsettling. As the car drove off, I went chest down on the bonnet, looking into the windscreen – and then I rolled over, and he swerved to throw me off and I landed, half-running, tumbling to the ground. But in the moment before I rolled over, I remember seeing the driver’s face and knowing that he had no more clue what to do next than I had, that we were caught in a shared helplessness.

It’s the end of the year and Anna and I take a couple of weeks offline to rest and reflect. Walking beside the lake in the small town where she grew up, we talk about this sense that something is shifting, and what this means for the work that seems worth doing now, how to frame what is at stake. ‘It’s about negotiating the surrender of our whole way of living,’ I say.

There’s a thing called the Overton window, the boundary of what is ‘thinkable’ to governments and decision-makers: what you can talk about and still get taken seriously, inside the rooms where the decisions get made. I have an image of the window as a windscreen, an expression of helplessness on the face behind the glass.

Unthinkable things are going to happen, that much seems clear.

‘You should stop going round saying we’re all going to die,’ someone who spent time in those rooms told me, years ago, in an early online argument about Dark Mountain. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever gone round saying that,’ I wrote back, ‘except in the non-apocalyptic sense that, sooner or later, we are all going to die.’

There are things you can’t see clearly through that window, possibilities that go unmarked on the maps according to which the decisions are taken. We can come alive in the face of the knowledge that we are all going to die. And in the meantime, before we die, we can try to live out some of those possibilities: the ways of being human together that are hidden from view when the world is seen through the lenses of the market and the state; the ways of feeding ourselves that get overlooked because they don’t work as commodities. We can try to negotiate the surrender of our way of living, without pretending there’s any promise that this would make it all OK, without pretending we even know what OK would look like. We can have some beauty before the story is over, without pretending we can be sure how long we’ve got.

* * *

It was Anna who came up with the name – before we thought of it as a school, when we were just talking about creating a hospitable place to bring these conversations together. ‘It’s not a centre,’ she said. ‘We’re not starting a community. It’s our home, and everything else starts from there.’ It doesn’t come into being on those weeks when we advertise a public course, when people we’ve yet to meet make long journeys to be here. Those are just the times when we’re able to open up the work that’s already going on: the conversations we bring together around the kitchen table, the people who come and stay, the thinking that gets done in their company. This part of the story is clearer now than when we made that first invitation to the course last June. We’re clearer, too, about the urgency: the need for quiet spaces where bridges can be built between troubled insiders, an awakening grassroots and what one of our collaborators, Vanessa Andreotti, has taught us to think of as the ‘knowledge-carriers at the edges’; spaces of negotiation, away from the frontlines. Clearer about the role of the network we have built, our ability to bring people together and the consequences this can have. So this is our answer, just now, the place where we might have something to contribute, the work we’re going to do.

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 15.

-

Deschooling Revisited

I grew up in a town in the northeast of England. Billy and I met at the local comprehensive, hanging out in the music department at lunchtime, a quiet corner where we would eat our sandwiches, teach ourselves to play the guitar, and keep out of the way of the hurlyburly that comes with keeping 1,500 hormonal adolescents cooped up alongside one another for a large part of their waking hours. Over the course of our teens, I watched his self-taught musicianship soar beyond my basic busking and came to the conclusion that I’d rather be a writer than a rock star, anyway, because you had a better chance of living past the age of 27.

Neither of us had heard of Ivan Illich, but when I discovered Deschooling Society in my mid-twenties, it gave words to things we’d known instinctively a decade earlier. There is an innate human capacity for learning, we are not dependent on learning transmitted from professionally accredited teachers, and the primary social function of the schooling system is to shape us for and assign us a place within the existing social order of the world.

This last lesson is mostly taught indirectly, by implication, but now and then you get a straight look at what you’re up against. Towards the end of Year 10, they would ship us all out on work experience for a couple of weeks, timed to quieten the place down while the year above sat their GCSEs – and perhaps also to chasten us into studying harder on our return so as to postpone our entry into regular employment. By that stage, Billy had developed a sideline in filmmaking and he’d arranged a placement with the video workshop at the back of the local arts centre. On the Friday before it was due to start, there was a hitch, some paperwork that was needed for insurance purposes. He spent the afternoon running around the school, tracking down the teacher who needed to sign off first one form and then another, and the second time around, this teacher snapped. ‘Why can’t you just go and do your work experience in an office like everybody else?’ she said. ‘After all, it’s what you’ll be doing for the rest of your life.’

At this point, I’m obliged to insert a disclaimer that the woman in question had doubtless had a shitty day, and not all teachers think this way about their students – and of course I’ve known wonderful teachers, not to mention wonderful people who tried working as teachers and were burned out by the system.

But it’s the system Illich has in his sights – and for him, it is beyond reform. What’s wrong with our schools is not that they are too liberal or too conservative, too hidebound or trendy in their curricula. For a strongly motivated student, he writes at one point, there are many skills where the discipline of drill teaching and learning by rote is preferable. The problem is that we have structured a society in which huge amounts of resources go into educational institutions which work against the grain of motivation, which initiate us into a needy dependence on scarce commodities – and which lend a rubber stamp of meritocracy to the perpetuation of privilege, since access to desirable fields of work is routinely subject to discrimination on the grounds of how many years the applicant has spent in formal education, whether or not the education in question has any connection to the skills actually required for the job. Needless to say, the strongest indicator of how many years of education an individual is likely to complete is the educational and financial privilege of their parents.

Deschooling Society was written in the early 1970s and some parts of Illich’s analysis have aged better than others. His vision for ‘learning webs’, using a database system to connect learners outside of institutions, may seem prophetic of the internet age (and inspired the web startup I co-founded in the 2000s), but by the end of his life Illich himself had become deeply sceptical of the hope invested in networked technologies.

On the other hand, revisiting this book in early 2019 – with the Fridays For the Future school strikes spreading across 130 countries – his idea that school might be the most hopeful location from which revolutionary change could erupt seems less quixotic than it did to his fellow revolutionaries in the 1970s. ‘The risks of a revolt against school are unforeseeable,’ he writes, ‘but they are not as horrible as those of a revolution starting in any other major institution … The weapons of the truant officer … might turn out to be powerless against the surge of a mass movement.’

Meanwhile, this summer it will be 25 years since we sat our GCSEs. Not long ago I was invited to a Facebook group for organising a reunion. It’s fair to say my life has taken a different direction to most of those I was at school with, but as we each shared the potted version of what happened on the way to our forties, I was struck by how many of the stories involved dropping out of college or university, or following a course that led nowhere, until somewhere further into adulthood you’d find something that actually felt like you – and maybe even go back to school for the necessary study or training. Only this time around, you were there for your own reasons.

First published in STIR: Issue 25.

-

… as sure as the rain

Back in 2012, Anna and I travelled to Oaxaca with our friend Nick Stewart, an artist and regular co-conspirator from my London days. We had in mind to make a film together that would centre on my conversations with Gustavo Esteva – the activist, ‘deprofessionalised intellectual’, friend of Ivan Illich, political advisor to the Zapatistas and founder of the Universidad de la Tierra.

These things don’t always turn out the way you expect. Back in England, in the cutting room, it dawned on us that the conversations we’d filmed worked better as a transcript than they did on screen – and this transcript became the basis for Dealing With Our Own Shit, a text that was published in Issue 4 of Dark Mountain. (One suggestion that Gustavo made to me, in particular, became the starting point for a whole strand of work on friendship and the commons, beginning with the talk I gave at the Commoning the City conference in Stockholm in April 2013.)

Meanwhile, Nick had returned from Mexico with an extraordinary collection of footage, shot from the hip as we wandered around Oaxaca and later Cuernavaca, where we took part in a conference to mark the tenth anniversary of Illich’s death. The images that accumulated on camera were almost implausibly suggestive – from the men at work with sledgehammers, smashing up the sidewalk below the Hotel America, to the schoolchildren queuing to be led into an inflatable globe, to the graduation ceremony taking place in a university sports hall, where a gulf of empty floor separates the assembled parents from their offspring.

All of this and more, Nick had stumbled across during those days. The puzzle was what to do with it all. And then he met the Mexican writer and artist Helen Blejerman, and their conversation became an exchange of stories, like letters read aloud, about memories from their childhoods in Mexico and Ireland. Together with the music of Nils Fram, Nick and Helen’s stories are woven together with the scenes from Oaxaca into a feature-length film essay, …as sure as the rain.

You can watch the trailer below – or the whole film here.

And if you watch closely, you may notice a hairy silhouette on the edge of the frame, or two tall white folks arm in arm in the middle of a Oaxacan street market; traces of the journey in which this film had its beginnings. It all seems a long time ago now.

-

Endangered Knowledge: A Report on the Dark Mountain Project

The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop. Together, we will find the hope beyond hope, the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us.

Closing lines of Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto (2009)Almost a decade ago, Paul Kingsnorth and I published a twenty-page manifesto. Out of that manifesto grew a cultural movement: a rooted and branching network of creative activity, centred on the Dark Mountain journal, which has been variously described as ‘the world’s slowest, most thoughtful think tank’ (Geographical), ‘changing the environmental debate in Britain and the rest of Europe’ (The New York Times), a case study in clinical ‘catastrophism’ (Paul Hoggett, Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, Vol.16,3, 261-275) and ‘a form of psychosis [likely to] create more corpses than ever dreamed of by even the Unabomber’ (Bryan Appleyard, New Statesman). The diversity of these responses gives some indication of the difficulty of summarising the Dark Mountain Project and the ‘charged’ nature of the cultural terrain in which the project has been operating.

Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto was written in the autumn of 2008, as the financial system shook to its foundations, and it grew out of a sense that our whole way of living – ‘life as we know it’ – was endangered. While the rolling news that autumn gave an immediate edge to that sense of endangerment, our concern was not only with the self-wrought destabilisation of the project of economic globalisation, but the fraying of the ecological foundations of this way of living by the consequences of industrial exploitation. Against such a background, the manifesto calls for a questioning of the stories our societies like to tell about the world and our place within it: the myth of progress, the myth of human separation from nature, the myth of civilisation. And it claims a particular role for storytellers and culturemakers in a time when the stories we live by have become untenable.

Ten years on, I would locate the cultural and intellectual project set out in the manifesto as bordering onto the work of Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing (the abandonment of the ‘dreams of modernization and progress’ and the multispecies storytelling of The Mushroom at the End of the World), Amitav Ghosh (The Great Derangement), Deborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (The Ends of the World) and the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures collective, as well as James C. Scott (Against the Grain), who having assembled the archaeological evidence against the myth of civilisation, writes despairingly:

‘Dislodging this narrative from the world’s imagination is well nigh impossible; the twelve-step recovery program required to accomplish that beggars the imagination.’

Meanwhile, among those working directly with climate change, there is an increasing willingness to voice the question at the heart of the manifesto: if this way of living cannot be made ‘sustainable’ and a great deal of loss is already written into the story, what kinds of action continue to make sense? See, for example, Jem Bendell’s work on ‘The Deep Adaptation Agenda’, or the recent Guardian interview with Mayer Hillman (‘“We’re doomed”: Mayer Hillman on the climate reality no one else will dare mention’).

As discussed in that article, there is a lag between the willingness of artists and writers to contemplate the possibility that we are already living through an event that might well be described as ‘the end of our civilisation’ and the willingness of scientists to suggest that this is the case. Perhaps there is a parallel here to what has happened over the past decade with the Anthropocene, a concept which is still following the slow process of authentication at the International Commission on Stratigraphy, but which has already been the subject of vast amounts of artistic and intellectual output.

Even more than with the Anthropocene, there is a clash between attempting to write about this subject in reasonable prose and the content of what is being written about. Much of the early criticism of Dark Mountain seems to waver between a moral objection (‘you are giving up and if people listen to you, the consequences will be terrible’) and an existential recoil (‘this is unbearable to think about’). In relation to the second of these, the artistic nature of the project is important: as I have argued elsewhere, one of the roles of art under the shadow of climate change can be to create spaces in which we are able to stay with unbearable knowledge, without falling into denial or desensitization.

Concerning the charge of ‘giving up’, as Paul Kingsnorth wrote in the early days of the project, there is something missing here: ‘giving up’ on what? There are those who move from giving up on the project of sustaining our current way of living to embracing the imminence of human extinction (see Guy McPherson). From the manifesto onwards, however, Dark Mountain has sought to open up the considerable territory which lies between these two outcomes. ‘That civilisations fall, sooner or later, is as much a law of history as gravity is a law of physics,’ we write in the manifesto.

John Michael Greer, a regular contributor Dark Mountain, offers the helpful distinction between a ‘problem’ and a ‘predicament’. A problem is a thing that has a solution: it can be fixed and made to go away, leaving the overall situation essentially unchanged. A predicament is a thing that has no solution:

‘Faced with a predicament, people come up with responses. Those responses may succeed, they may fail, or they may fall somewhere in between, but none of them “solves” the predicament, in the sense that none of them makes it go away.’

The claim which Dark Mountain makes is that our situation cannot be reduced to a set of problems in need of technical or political solutions. Rather, it is best conceived as a predicament. In the face of a predicament, it is not that there are no actions worth taking, but the actions available belong to a different category to those one would take when faced with a problem.

If I were to propose a list of the kinds of action worth taking in the face of our current predicament, it would include:

- taking responsibility for kinds of knowledge which might not survive the likely turbulence of the coming decades and doing what you can to better their chances of survival;

- making sure that the losses (of species, landscapes and languages) which already form the background to our way of living are mourned rather than forgotten, not least by telling stories of loss which themselves become a form of knowledge that can be carried with us;

- creating circumstances under which we have a chance of ‘knowing what we know’, encountering the knowledge of a thing like climate change not as arms-length facts, but as the experience of knowing by which my sense of who I am is changed.

In each of these three cases, the work of writers and artists, storytellers and culturemakers has a role to play – and these roles have been explored over the past ten years in the work that has taken place around Dark Mountain. So far, the project has been responsible for thirteen book-length collections of writing and art, while inspiring manifestations as various as a number one album in the Norwegian music charts, an enormous mural on the side of a disused art college in Doncaster, and a year-long workshop at Sweden’s national theatre. To the best of my knowledge, it has not been responsible for any corpses.

First published in KULA: Knowledge Creation, Dissemination, and Preservation Studies as part of a special issue on ‘Endangered Knowledge’

-

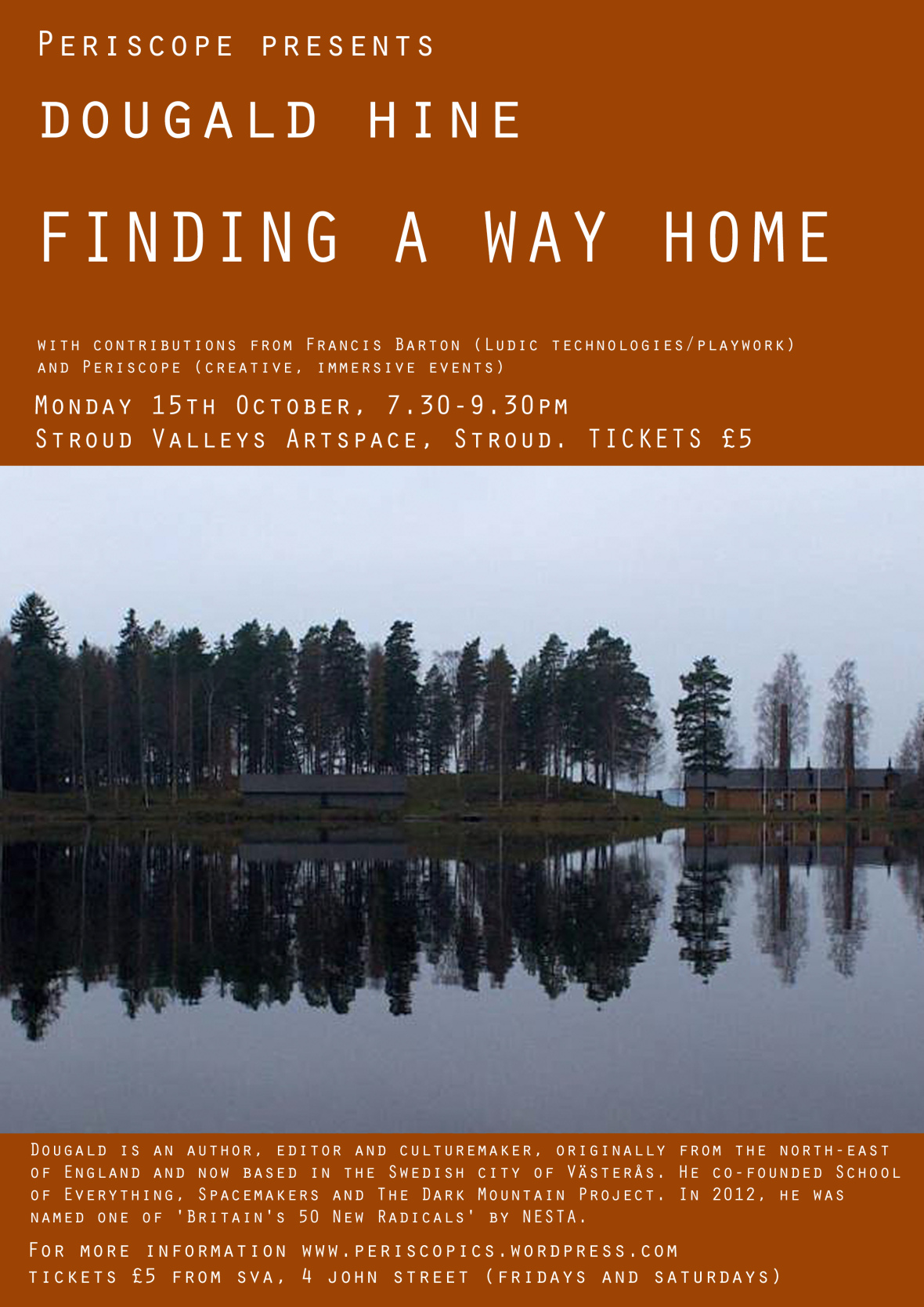

Finding A Way Home: Stroud, 15 October 2018

There’s a phrase we use to describe this school called HOME: ‘a gathering place and a learning community for those who are drawn to the work of regrowing a living culture.’ It’s a vision that we’re starting to realise, with all the stumbling and humbling moments that go with bringing any project into reality – and an important step towards that was the course that we held in June, when twenty-two scholars converged on our corner of Sweden for five days for Finding Our Way Home.

So when planning a trip to England for the Convivial Tools symposium (13 October), I was very pleased to get an invitation from one of our scholars, Francis Barton, to come and speak on his home ground in Stroud. I’m looking forward to the chance to talk more about what it can mean to talk about ‘the work of regrowing a living culture’.

The evening will include contributions from Francis and me, along with our hosts, Emily Joy and Alison Cockcroft of Periscope, the arts organisation who have made this event possible.

Tickets are available in advance from the venue – Stroud Valleys Artspace, 4 John Street, Stroud – or if travelling from further afield, you can contact Periscope about reserving a ticket.

More details here.

-

Convivial Tools: The Design Museum, London, 13 October

During the next several years I intend to work on an epilogue to the industrial age…

With these words, Ivan Illich opens Tools for Conviviality (1973), one of the series of short books written at the height of his fame. This month, the Design Museum in London are hosting a day-long symposium to explore the possibilities for Convivial Tools today. There’s a great line-up – and I was delighted to be asked to offer a reflection as part of the day’s programme.

In the early 1970s, Illich could write that ‘two-thirds of mankind still can avoid passing through the industrial age’. As his friend, the historian Barbara Duden records:

He gradually moved away from assumptions that sparked so much of his writing in the 1950s and 1960s, a vision of salvaging a life worth living for human beings by protecting “communality” and what he called “the commons”, by calling to mind the “tools of conviviality,” by preserving traditional and customary ways of living. Even he was amazed by the breathtakingly rapid disappearance of “traditional” orientations and practices in Third World villages, and he shed his own illusions that the social critic could help protect the fabric of these villages.

The Illich of Tools for Conviviality is not as conservative as Duden’s summary makes him sound, but there is throughout his work an attentiveness to what is being lost – and also to the past as a mirror in which we come to recognise the strangeness of the present.

In my contribution to the Convivial Tools symposium, I want to bring in some of Illich’s thinking about the past, to see if it can help us make sense of ‘the shadow that the future throws’, more than fifteen years after his death. I’ll draw on my own journeyings with Illich’s friends and co-conspirators, from Cuernavaca to Tuscany. And I’ll try to give a glimpse of the hope that I find in work which has often been dismissed as negative or pessimistic.

Tickets are available for the event here.

-

Coming Down the Mountain

After ten years of holding the space of Dark Mountain – the space between stories, the place you come when things you once believed in no longer make sense – it’s time for me to move on. I won’t be leaving overnight, but I’m now working to finish up or hand over the bits for which I’m responsible, and once we’ve celebrated the tenth anniversary of the manifesto next July, I’ll wander off to join those friends and collaborators who are already part of the project’s past. (more…)

-

Ten Years on a Mountain: A Farewell

There’s an old mythic way of thinking about the journey of a life which says that there are three times you will pass through, each with its own colour. You set out in the red time of youth, its raw energy not yet tempered by experience – and with luck, you are headed for the white time of wisdom. But whichever route you find yourself taking, the road that leads from red to white will pass through the black time, when that early raw energy starts to run low, when you are brought up hard against the knowledge of limits and you learn the humbling lessons of failure.

They say there have been times and places in which this was recognised and accounted for in the expectations your community would put upon you. On entering the black time, your other duties were taken away and you would join the cinder-biters, whose only task was to lay down by the fire and make sure it did not go out.

Who has such a community now? Hardly anyone. And most of us have grown up in a culture which prizes the red time of youth, and may look fondly on the occasional white-haired elder, but would rather not acknowledge the black times. So we struggle through, as best we can – or perhaps we find ourselves in a doctor’s office, being offered pills that promise to take the edge off the darkness. What we’re rarely offered is a story that might help us make sense of the time in which we find ourselves.

* * *

Ten years ago, when Paul and I were kicking around the draft of what became the Dark Mountain manifesto, neither of us had the tools to think in terms like these. The first I heard of cinder-biters or the three colours of initiation was from the storyteller Martin Shaw, one of the host of friends and teachers and collaborators who came into our lives as a consequence of having written that manifesto.

But when I look back now at the beginnings of Dark Mountain, I see two men who stood on either side of a threshold. There’s only five years between us, but we met when I was in the last rush of the red years, having stumbled at last on something I was good at doing, while Paul was already deep in the black.

I’m not spilling secrets here; it’s written across those essays of his which led so many readers to this project. The loss of faith in journalism and environmentalism, but also the way ambition turns to ashes: ‘I used to long to be on Newsnight every week, offering up my Very Important Opinions to the world,’ Paul writes, in Issue 2, grimacing at the memory of his younger self.

Part of my role in those early years was to serve as a counterweight. I remember a mutual friend suggesting that Dark Mountain had been born out of Paul’s loss of faith and my finding a faith. In what, though? There are traces of it in the manifesto: that insistence on ‘the hope beyond hope’, ‘the paths which lead to the unknown world ahead of us’, and ‘the power of stories in making the world’.

‘It is time to look for new paths and new stories,’ we declare in the manifesto’s closing chapter, announcing our intention to create a journal that will be a home for this work. But as others joined the conversation, they led us to a recognition that the work is as much about recovering old stories, stories from the margins – and, in a phrase I remember hearing in those early conversations, holding ‘the space between stories’: the place where you can slow down, wait a while in the ashes of a story that failed, rather than rush headlong into ‘the new story’ and repeat the same mistakes.

In Issue 4, I published a conversation with the Mexican intellectual and activist Gustavo Esteva, the only person Paul and I had known in common when we first met to share ideas for what became Dark Mountain. At one point, I talk about:

the willingness to walk away, even though you have no answers to give when people ask what you would do instead, to walk away with only your uncertainty, rather than to stay with certainties in which you no longer believe.

It’s a description of a pattern I saw in Gustavo’s life, but also of a pattern I’d begun to recognise around Dark Mountain. It’s Paul declaring, at the end of his essay in Issue 1: ‘I withdraw … I am leaving. I am going out walking.’ It’s what I understood from those words about ‘the space between stories’. It’s a journey I’ve seen others make over the past ten years: taking leave of hollowed-out stories and certainties in which they could no longer believe, resisting the rush to answers and to action, laying in the ashes for a while.

‘It’s a good name, you know, Dark Mountain.’ This was Martin Shaw, in the garden of a Devon pub, the first time we actually met. ‘It’s good because you’ve got an image there.’

The sun moves across the sky, the seasons change and the face of a mountain shifts; features emerge or pass into shadow. The same thing will happen with an image, different sides of it catch the light in different moods, at different times of life.

Long after Paul had introduced me to Robinson Jeffers’ ‘Rearmament’, the poem where he found the image that gave us a name, another aspect began to come into focus. More and more, I found myself drawn to the role that mountains have played as places of retreat, in both the spiritual and the tactical senses of that word. It caught something about the role Dark Mountain seemed to play for many of those to whom it mattered.

You come here because it’s a good way back from the frontline. You come here when you’re no longer sure where the lines are drawn, when the maps are shaken and old identities scattered. You come here when it’s time to reflect, to ground yourself again, or to catch the whispering of realities that get drowned out in the street-noise of the everyday world. Maybe you build a shelter for a while, sit around a campfire with strangers who feel like friends, and look back at the orange lights of civilisation: just now, they seem a long way away. But you are not made of granite, peat or heather.

There may not be much talk of ashes in the culture I grew up in, but we still know what it means to get ‘burned out’ – and by the time I left England in 2012, three years into the life of this project, I was burning out.

I’d spent those red years running around London, bringing together conversations, watching ideas spark, learning to breathe projects into life. I was good with words, but I wasn’t a writer exactly – or not the way that Paul was. My role models were never the solitary romantic figure, the lone truth-teller set against the world; they were collaborators whose work took many forms, John Berger or Ivan Illich, thinkers and storytellers whose words were tangled up with webs of friendship and mutual inspiration. Following the threads I found there, I’d discovered that I could use words to create a space of possibility, a story others would want to step inside.

There’s an energy that comes with learning to use your own abilities and finding that you have an effect in the world. Fuelled by self-discovery, you burn brightly – but then one day you realise you’re falling, you have been falling for a while, and only the forward momentum kept you from crashing already.

I was lucky. Just as I entered freefall, I met someone who was willing to catch me. I moved countries, shucked off what I could of the responsibilities I’d been carrying, in the name of self-preservation – and over the next eighteen months, my involvement with Dark Mountain was limited to a few weeks of editing and a couple of pieces published in the books

‘Everyone I meet at Uncivilisation is an individual with a collective story to tell.’ This was Charlotte Du Cann, writing in 2011, about her first visit to the annual festival we used to run back then. ‘A poet from Scotland, a professional forager, the captain of a Greenpeace ship, a designer of hydrogen cars, a researcher into Luddite history.’

I still occasionally encounter people who think Dark Mountain is a campaign to persuade everyone to give up – on climate activism, on saving the world, on the possibility that there is anything worth doing. Given the picture they seem to have of our project, I always wonder what they imagine could fill the soon-to-be fourteen volumes of that journal we proposed in the manifesto, what could have sustained the love and work of all the editors who have brought those books into being.

I don’t remember meeting anyone at Uncivilisation who was seduced into despair by Dark Mountain – although there were those who had been deep in despair when they stumbled on the project, and who found relief in a setting where it was possible to give voice to a loss of faith without feeling judged or isolated. But like the contributors to our books, the temporary community of the festival was disproportionately made up of people who are active in one way or another, whether or not they would identify as activists.

Yet here’s the twist: Dark Mountain itself has never been the place from which to act. You come here for something else, something harder to pin down. Something you’ve been missing.

Charlotte came across one way of naming this in a conversation with a Transition Towns activist she met that summer at Uncivilisation: ‘If Transition is the village,’ he told her, ‘Dark Mountain is the shaman.’ In her report on the festival, she ran with this personification, Dark Mountain as the outlandish figure, walking the boundary between the human world and what lies beyond:

to transmit a sense of deep time, of our rough lineage, of wild trees, of the ease and intimacy of talking about Big Subjects, without being heartless, idealistic, or controlling the outcome.

This is a picture of the project that I recognise – and in hindsight, there seems to be a line running from that festival report to the role that Charlotte would come to play at the heart of Dark Mountain in the years that followed, bringing a new degree of beauty to the books and shouldering the heavy-lifting of a growing project, as it matured beyond its beginnings.

Paul’s head may not actually have been in his hands, but that’s the way I remember it. And I remember the thoughts that ran through my head: Paul couldn’t go on carrying this much weight, and it wasn’t time for this thing to come to an end, and no one was going to magically ride to our rescue, so I was going to have to step back in.

They say what changes, on the far side of the black time, is that you put your life in service of something larger. I may be greyer around the edges than I was ten years ago, but I’m not laying claim to any white-haired wisdom. All I’m saying is, that morning in Ulverston was the first time I chose to put this project ahead of my own interests, and probably the first time I really had to make that kind of choice about anything.

I’d given a lot to Dark Mountain before that, but now I was in service to it. This meant teaching myself how to do whatever was needed: replacing the book-by-book crowdfunding with an annual subscription, setting up a cash flow model so we knew that there would be money in the bank to print the books, mediating the tensions that built up between members of a growing team, setting up regular calls so we actually started to function as a team. In an ordinary week, there were others who put more hours into the running of the project, but when a crisis hit – and in those days, it seemed like that was every other month – I was the one who’d interrupt a family holiday, turn down paid work and generally drive those I loved to distraction, as I threw myself into keeping the show on the road.

‘In dreams begins responsibility,’ wrote Yeats. To leave room for making a living, I gave up my role as an editor on the books, and the tasks I was doing now for Dark Mountain were not the things I enjoyed most or was even that good at. But I was here, and it wasn’t time for this to come to an end, and there’s a certain satisfaction that comes with taking responsibility.

In my memory of the festivals, there was always a moment – around the Sunday morning – when people’s thoughts began to turn for home, and someone would start a big conversation with the question: ‘So, what are we going to do?’

My answer was no: we weren’t going to do anything, and we certainly weren’t going to sit down now and arrive at a consensus, make a plan of action, organise ourselves into a movement.

Probably this scene played itself out in my head, more than anywhere else, but the dynamic was real enough. Over those days together, many of us had felt a quickening, a sense of coming alive – and it was tempting to try to turn this into action. But pledges made in that liminal space are a prescription for disappointment.

What was called for wasn’t, couldn’t be, a collective decision forged in a festival tent. Rather, the challenge now was for each of us to take whatever we had found here back to the everyday world, back to the frontlines or backyards or office cubicles that were waiting for us, and see which parts of it survived the journey. However inspired we felt right now, there was no shortcut, and no guarantee which parts of what we were feeling would still make sense on a Monday morning in October.

Retreat is not defeat. Retreat is not surrender. A mountain can be a pretty picture on a postcard, or a place you sit alone for days and nights as the layers of your life so far get burned away and you get claimed by something larger. If that should happen to you, then you’ll come back changed. You’ll have lost some of what you thought you were, certain paths will no longer hold the attraction they once did, and you may catch sight of possibilities you couldn’t see before. If you sit for long enough, your eyes adjust.

But none of us can spend our whole lives on a mountain. At the practical level, where dreams give way to responsibilities, none of us makes a full-time living from our work with Dark Mountain. It’s probably healthy that we fit our roles in around other freelance projects, creative commitments and part-time jobs that pay the bills and take us into other worlds.

Still, if you take on a role where you’re seen as speaking for the project, where you get written about periodically in the press with varying degrees of accuracy, then inevitably you become identified with it, and it with you.

For the best part of ten years, I’ve been one of the Dark Mountain guys. (‘The one you haven’t heard of,’ as I remember Chris T-T described me during his set at the manifesto launch.) And for a while now, I’ve known that my time in this role is coming to an end. I’ve served this project and been blessed by it in more ways than there’s room to tell and I’m ready to move on.

I’m ready to head back down the mountain, to take my place again somewhere along ‘the long front’, as Doug Tompkins called it in Issue 3. Here in Sweden, Anna and I are starting a school called HOME, ‘a gathering place and a learning community for those who are drawn to the work of regrowing a living culture’. This is a different task to the one Dark Mountain serves, and there’s a need to be clear about the difference, which is one of the reasons why it’s time to be moving on.

I won’t be leaving overnight – there’s still work to finish up, helping the rest of the team to fulfil the promise of this new online home, editing some wonderful pieces that have already been sitting on my desk too long, and getting the business side of running Dark Mountain into as tidy a shape as I can before I go. But next July, I plan to walk the Thames from London to Oxford with my family, to arrive on the tenth anniversary of the manifesto’s publication at the riverside pub where it was launched, to celebrate the occasion with a party to which all friends of this project are invited – and then to wander off to join those friends and collaborators who are already a part of the past of Dark Mountain.

For years, I struggled to articulate the asymmetry between my relationship to Dark Mountain and Paul’s. He was always generous in naming me as his co-founder, but he was the one with whom it started.

One time, I tried to explain it to a journalist by talking about the idea of ‘the first follower’, from this little video about ‘how a movement starts’: that the critical moment isn’t the guy dancing like a wild thing on the hillside, but the first person who gets up and starts dancing with him. When I read it in print, it came out like I’d proclaimed myself his number one disciple.

Then this summer, I realised what it is: for me, Dark Mountain was always a collaboration. Each of us brought years of our thoughts and doubts and inspirations to the beginnings of the project – but for Paul, there had been a time when Dark Mountain only existed in his head, a thing that was brewing, that he knew he would need help to bring about.

As I look to the end of my time with this project, then, I find myself thinking about its future as a collaboration. It’s no longer a start-up that hits a potentially terminal crisis every other month. And for a long time now, it’s been sustained by the collective creativity and strength of a team who have taken it further than I’d have believed possible in those early years.

At the heart of that team are Charlotte and her partner Mark Watson, both as much in service to this project as I’ve ever been, along with Nick Hunt and Ava Osbiston, and a growing gang of experienced editors, readers and steerers around them. There’s plenty of strength there to carry things forwards – but just as they joined me and Paul and lifted the weight from our shoulders, so others will be needed to join them along the road.

The seasons will change, the sun will move across the sky and other features of the mountain come into focus. The image will be read in other ways. There is never only one map you can draw of a given landscape, never only one path that leads across it. I look forward to lifting my eyes from time to time and catching sight of you, all you mountaineers, tracing paths that I would never have thought of taking, until one day you find that it is time for this thing to come to an end – and when that day comes, know that ending is fulfilment and not failure.

First published in the online edition of Dark Mountain in October 2018 to accompany the announcement of my departure from the project.