I have been thinking about the slipperiness of history, how it escapes our grasp. When we study a war in school, the first facts we learn are the last to be known to anyone who lived through it: when it was over and which side won. Those who do not remember the past may be condemned to repeat it, but hindsight is very nearly the opposite of memory. To remember is to be returned to a reality that was not yet inevitable, to recall the events which shaped our lives when they might still have gone otherwise.

‘The Dark Shapes Ahead’ (2012)

The world is in flames and if you think it’s all the fault of those people — the uneducated, the bigoted — I urge you to think harder.

When the values of social liberalism got hitched to the mercilessness of neoliberalism, it kindled a resentment towards the former among the latter’s losers. The deal was summed up in Alan Wolfe’s formulation: ‘The right won the economic war, the left won the cultural war and the centre won the political war.’ He said that in 1999. It was under Bill Clinton’s presidency that the ‘centrist’ settlement between progressive cultural values and There Is No Alternative economics was consummated. Two decades on, that made Hilary Clinton the dream opponent for a candidate running on the fuel of resentment.

Here’s a stony truth to stomach: today, across the western countries, the culture war to defend the real social achievements of the past half century is grimly entangled with a class war against the losers of neoliberalism.

If we now lose many of the unfinished achievements of the struggles against racism, sexism and homophobia, the Clinton generation of politicians will share the responsibility.

I came home on Tuesday thinking Clinton was going to win, just like I came home in June thinking Britain was going to vote Remain.

It turns out you can spend the best part of a decade talking “collapsonomics”, writing about the dark shapes ahead and the unravelling of the world as we have known it, and still let yourself get lulled into believing the status quo will hold a little longer.

It helps that I voted Remain. I would have voted Hilary if they gave the rest of the world a vote.

Still, the day after the referendum, when everyone was sharing that chart that showed that Remain voters were better educated, it filled me with an anger that stopped me writing. Were so many of you really so blind to the link between education and privilege?

Back before I was that Dark Mountain guy, I worked as a local radio reporter in a city in the north of England. In the newsroom one day I saw a set of figures that are fixed in my memory: among 19 year olds with a home address in the leafy suburban southwest of that city, 62% were in higher education; on the council estates and terraced streets to the northeast, where my sister lives, the number was 12%. A kid from the right side of town was five times more likely to get to university than a kid from the wrong side of town. That’s when I got it: for all the other things it does, the major social function of higher education today is to put a meritocratic rubberstamp on the perpetuation of privilege.

All those posts pointing out that graduates voted Remain, they seemed to imply that the higher you climb the ladder of education, the further you can see, the better equipped you are to make important decisions. But there are truths that are seen more clearly from below. Which side of town would you imagine has a clearer picture of the link between education and privilege?

On Twitter right now, pundits who seem unhumbled by all the ways they didn’t see this coming throw around snapshots of exit polls to prove that this was or wasn’t about misogyny, racism, or a working class revolt.

Start with a different set of numbers.

Last September, the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton published a study that showed that the death rate for middle-aged white Americans had started rising back in 1999. For every other group in the population, the death rate continues to fall. Among middle-aged white Americans, it is those who left education earliest who are doing most of the dying. They are dying of suicides and overdoses, alcohol poisoning and liver disease. The number of deaths is on a par with the AIDS epidemic at its height, but the causes bring to mind another historical parallel, to Russia in the years after the fall of the Soviet Union. Yet this American fall has taken place uneventfully, almost unnoticed, even by the gatherers of statistics: by their own account, Case and Deaton stumbled on their findings by accident.

In March, after Super Tuesday, the Washington Post plotted the death data against the primary results. In eight out of nine states, they found a correlation: the counties where death rates for middle-aged whites were the highest were the counties where the vote for Trump was the strongest.

I don’t know how you can look at that and say that Trump’s election is only about racism and misogyny, that it is not also a consequence of something that has been going terribly wrong in the lives of those white Americans with the lowest cultural capital.

All year I’ve been watching sensible respectable well-paid commentators flailing to catch up with the collapse bloggers: these fringe thinkers off the internet, narrators of America’s long decline, people I’ve been reading (and occasionally publishing) for a decade or so, were the one group whose models of reality could handle what was happening.

John Michael Greer lives in the Rust Belt and writes The Archdruid Report, a blog that rolls out every Wednesday, a kind of midweek sermon on nature, culture and the future of industrial civilisation. He called the election for Trump back in January. He is an actual archdruid, as it happens — as well as an SF novelist, a freemason and a self-described ‘moderate Burkean conservative’.

In a series of posts this year, he sketched out a take on the long backstory to this election which goes something like this:

Politics is about how a society deals with the collision between the interests of different groups. The great contribution of the liberal tradition was to show that politics can also be about values — but the corruption of that comes at the point when values are used as a cover for interests.

The policies of globalisation, the deindustrialisation of the US economy and its increased reliance on illegal immigration as a source of cheap labour, were the result of political choices. These choices served the interests of those Americans with salaries and a higher education, while going against the interests of wage-workers. But instead of this collision of interests being negotiated within the political sphere, the results of these policies were presented as inevitable and universally desirable. In particular, any attempt to talk about whose interests were served by the role of illegal immigration was immediately derailed into an argument about values where anyone questioning immigration was accused of racism.

Trump’s campaign played on this in two ways. First, by deliberately outraging the socially liberal values which had become so entangled with the interests of the salariat, he could build a rapport with other parts of the electorate. Then, by focusing on immigration, jobs and protectionism, he gave those voters a sense that their interests might actually have found a political vehicle.

The danger of this kind of analysis is that it downplays the uglier forces on which Candidate Trump fed for his success, the forces which President Trump will embody. But it gives you a sense of how the election can have looked in the Rust Belt towns, to the low income white Obama voters who swung to Trump, in the places where all that dying is going on.

More than anyone else I’ve read this week, Greer seems persuaded that the dangers of a Trump presidency have been overstated. It’s possible to hope that he is right, I suppose — and, meanwhile, to assume that he is wrong and prepare accordingly.

The blogger who goes by Anne Tagonist (or sometimes Anne Amnesia) is less sanguine. ‘What Trump’s boys have for me is a noose,’ she wrote, back in May, ‘but that’s the choice I’m facing, a lifetime of gruelling poverty, or apocalypse.’

Yeah I know, not fun and games — the shouts, the smashing glass, the headlights on the lawn, but what am I supposed to do, raise my kid to stay one step ahead of the inspectors and don’t, for the love of god, don’t ever miss a payment on your speeding ticket? A noose is something I know how to fight. A hole in the frame of my car is not. A lifetime of feeling that sense, that “ohhhh, shiiiiiit…” of recognition that another year will go by without any major change in the way of things, little misfortunes upon misfortunes… a lifetime of paying a grand a month to the same financial industry busily padding the 401k plans of cyclists in spandex, who declare a new era of prosperity in America? Who can find clarity, a sense of self, any kind of redemption in that world?’

When I interviewed Anne for the last Dark Mountain book, I learned a little more about her background in zine writing and travelling and roads protests, working as a street medic, then on ambulances, and from there to medical school and research. She doesn’t write so often, but when she does, what I appreciate is her willingness to puzzle through a question, to include her uncertainties, rather than making a neatly rounded argument.

And that post in May was scorching. It starts with the Case-Deaton death rate study, but seen through the eyes of someone living in one of those counties, someone who has been sitting in with the Medical Examiner:

A typical day would include three overdoses, one infant suffocated by an intoxicated parent sleeping on top of them, one suicide, and one other autopsy that could be anything from a tree-felling accident to a car wreck (this distribution reflects that not all bodies are autopsied, obviously.) You start to long for the car wrecks…

Unlike the AIDS crisis, there’s no sense of oppressive doom over everyone. There is no overdose-death art. There are no musicals. There’s no community, rising up in anger, demanding someone bear witness to their grief. There’s no sympathy at all. The term of art in my part of the world is “dirtybutts.” Who cares? Let the dirtybutts die.

You know, I could just repost every other paragraph of that piece here, but really you should go read the whole thing.

From where I live, the world has drifted away. We aren’t precarious, we’re unnecessary. The money has gone to the top. The wages have gone to the top. The recovery has gone to the top. And what’s worst of all, everybody who matters seems basically pretty okay with that.

Is this OK, I wonder, just bombarding you with a reader’s digest of the apocalypse?

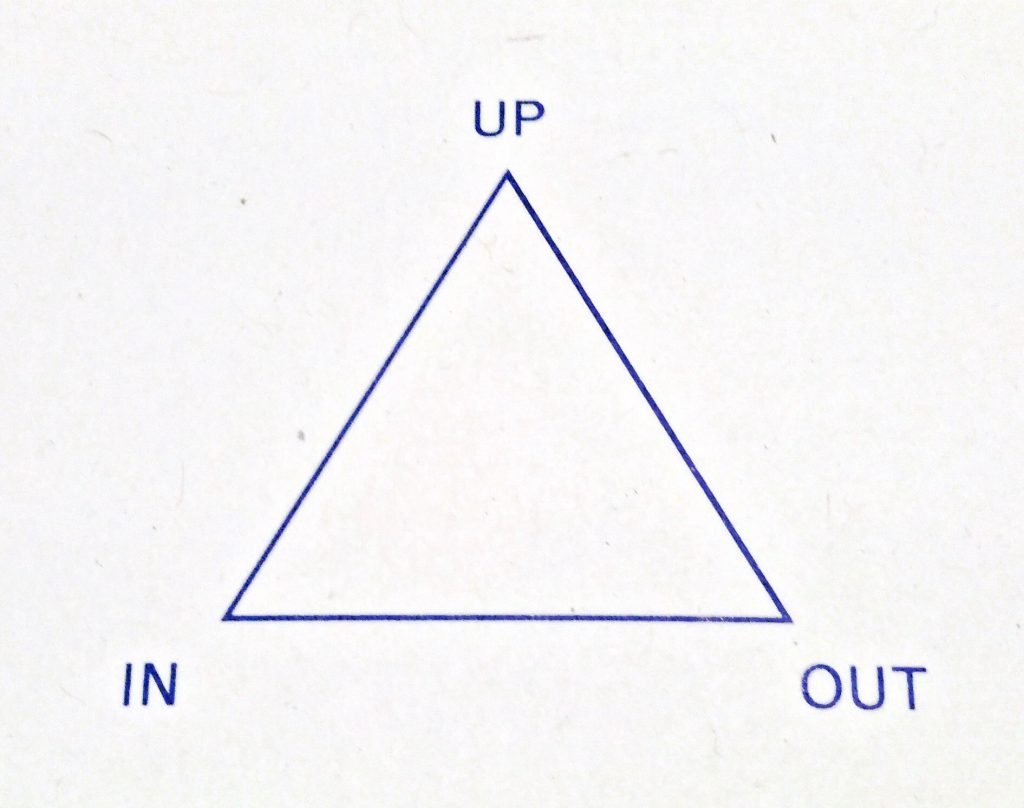

It’s not the apocalypse, of course, it’s just history, but if you thought the shape of history was meant to be an upward curve of progress, then this feels like the apocalypse.

Midway through the night, when the New York Times projection had slipped from Likely to Leaning to Tossup, as I broke open the whisky and let rip on Twitter, my friend Chris T-T replied, ‘I love that your reaction to fear is a splurge of analysis.’

There’s a rawness in the aftermath of nights like that, a sense that the callused outer skins of our grown-up selves have been ripped off. For a day or two, maybe longer, we can feel things with the intensity of children again. (Or as someone in my timeline wrote, ‘The OH FUCK! comes in waves.’)

It reminds me of the conversations that sometimes happen in the last days of a life, or on the evening of a funeral. In the underworld of loss, we don’t get to bring our achieved identities with us, so there’s a chance of getting real.

The morning after last year’s unexpected Conservative election victory in the UK, I wrote some notes on how to make sense of the loss. As political bereavements go, it looks quaint now by comparison — don’t you feel nostalgic for when the worst thing that could happen was waking up to find David Cameron was still prime minister? But one thing from that post sticks out, the part where I was building on a line from the mythographer and storyteller Martin Shaw: ‘This isn’t a hero time, this isn’t a goddess time: it’s a trickster time.’

When people like John Berger (one of my heroes) were young, it was a real thing to believe in the heroic revolution that Marx had seemed to promise. Today, the only kind of revolution that is plausible is a foolish one, one where we accidentally stumble into another way of being human together, making a living and making life work. (And whatever that might look like, it doesn’t look like utopia.)

I wrote that thinking of the weird cameo role that Russell Brand had been playing in British politics: not thinking of him as a candidate to lead a trickster revolution, only as a clue to the motley in which change would need to come in a time like this.

I’m pretty certain it was Ran Prieur, another of the collapse bloggers, who put me onto the idea of Trump as trickster, but the best treatment of that thought I’ve found is Corey Pein writing for the Baffler.

He starts with the story of Allen Dulles, later the director of the CIA, who recruited Carl Jung as an agent during World War II to provide insights on the psyche of Hitler and the German public. ‘Nobody will probably ever know how much Prof. Jung contributed to the Allied cause during the war,’ Dulles wrote afterwards. We do know that, in an essay in 1936, Jung had written, ‘the unfathomable depths of Wotan’s character explain more of National Socialism than all [proposed] reasonable factors put together.’ (As Pein goes to some lengths to acknowledge, such thoughts are quite a stretch for the early 21st century western imagination: if you’re struggling, try telling yourself, ‘Obviously Jungian archetypes are just metaphors,’ and then remove the ‘just’ from that statement.) If Wotan could be awoken in the collective psyche of a nation, Jung added, then ‘other veiled gods may be sleeping elsewhere.’ Which is how Pein comes to Trump:

Just as Hitler was not known to crack wise from the podium, Trump’s stump speeches do not call to mind ‘storm and frenzy.’ Trump is no Wotan, no berserker — he is a wisecracker, adept in the cool medium of television. He represents an entirely different Jungian archetype — namely, the pan-cultural mythological figure of ‘the trickster,’ who arrives at moments of uncertainty to bring change, often of the bad kind.

Pein is being a little unfair on the trickster here, I think. Lewis Hyde gives a subtler account in his marvellous book, Trickster Makes This World. He identifies trickster as a low status character within the local pantheon of a culture, a mischievous messenger boy, a nuisance under normal circumstances, but who takes on an altogether more important role in moments of deep cultural crisis: when those who hold high status within the existing order of things are helpless, trickster can shift the axis, find the hidden joke that allows the culture to pass through into a new version of itself.

If you’ll grant that such uncivilised ways of thinking could help us make sense of political events, I’ll tell you that Donald Trump is a shadowy parody of a trickster. That takes me to something the poet Nina Pick says in a conversation in the latest Dark Mountain:

We’ve lost the power of metaphor. You can see it in American politics at the moment for example; there’s a deficit of imagination, of the imaginal life, of myth… and without that level of myth and of metaphor I think we start to get lost as a culture.

When we lose sight of myth and metaphor, we don’t leave it behind, we just become unaware of the ways in which it is still at work in our culture.

Or, as Martin Shaw, who set me thinking about all this, would put it:

The stories that we are being fed now are not myths. They are what I would call, toxic mimics. But when we are deprived of the real thing, we will take even an echo and grab on to it. So in other words, the most horrible lies always have a little bit of truth in them.

So there you have it, that’s my hot take: Donald Trump is a toxic mimic of Loki.

At this point, there are a couple more things we need to talk about, before I try and leave you with some blessing for the dark times that are gathering around us.

There’s something more to say about the work that lies ahead, if it’s seriously the case that we are in territory where archdruids and zine writers and collapse bloggers and mythtellers are the ones who still have maps that seem to make sense.

But first, we need to talk about Hitler.

If there is any meaning left in a word like fascism, then let’s call Trump a fascist.

Heck, even John Michael Greer’s first take on the Donald’s campaign, back in the summer of 2015, was that it ‘is shaping up to be the loudest invocation of pure uninhibited führerprinzip since, oh, 1933 or so.’

But it’s worth lingering over that ‘if’… Words like ‘fascist’ are mostly used these days as a stop to thinking, a shorthand that saves us the work of knowing our enemy.

Anthony Barnett walked this line in an essay for Open Democracy, the night before the election:

It is essential to be able to distinguish between different kinds of evil and judge them accordingly… As a rule, therefore, never talk about ‘fascism’ or ‘Stalinism’ in political or polemical writing… They are used to mobilise an attitude that pre-empts scrutiny. And even interest. If something is fascist we should be able to ask what kind it is and how bad it might be, but the concentration camps make such an approach taboo.

‘For the first time,’ he goes on, ‘I break the rule.’

And if the hesitation adds force to his doing so, it also leaves room for a qualification. Trump is a fascist, Barnett writes, but unlike Hitler, he does not have financiers, storm-troopers or an organised movement. What he now has is the office of President of the United States and a seemingly compliant legislature.

Another line of caution about the Hitler comparison comes from another of Anne Tagonist’s essays — written just after Super Tuesday, when she was already taking the likelihood of a Trump presidency seriously — in a genre she calls ‘clumsy writings about why history doesn’t work the way you think it does.’

The systematic study of mass behaviour, she points out, is largely a post-World War II phenomenon.

In 1945, Germany was in ruins, the world had entered the atomic age and the cold war, Americans were starting to realize exactly how many civilians had been exterminated in “labour” camps, and yet no consensus narrative had emerged how such an unthinkable sequence of events could have happened… The Third Reich was a very good reason to go out and learn more about how humans behaved in groups.

And so, with the contributions of Adorno, Arendt, Milgram and others, within twenty years, an intellectual consensus emerged about how Nazism had come about, how it had achieved such adoration and power, and how it enlisted so many Germans in the systematic perpetration of horrors.

We had a system custom-built to explain the Nazis, that explained the Nazis. A side effect is that now, every large-scale bad social movement looks a bit like the Nazis.

Remember, she is not making this argument to tell us there’s no need to worry, this is Anne who also wrote that ‘What Trump’s boys have for me is a noose.’ What she is getting at is the danger of readying ourselves to fight the last war. Literally.

Actual historians don’t tend to think history repeats itself, or if they do, they find celebrated yet incomplete examples that don’t assume the world began a century ago and only one bad thing every happened in it.

But OK, let’s say that this is our January 1933.

We don’t know the shape of the war that could be coming, nor how that war will end, and not only because we cannot see the future, but because it hasn’t happened yet: there is still more than one way all this could play out, though the possibilities likely range from bad to worse.

Among the things that might be worth doing is to read some books from Germany in the 1920s and 30s, to get a better understanding of what Nazism looked like, before anyone could say for sure how the story would end.

Another thought, from that post I quoted at the start, written four years ago, on a journey I made in search of cultural resilience:

If someone were to ask me what kind of cause is sufficient to live for in dark times, the best answer I could give would be: to take responsibility for the survival of something that matters deeply. Whatever that is, your best action might then be to get it out of harm’s way, or to put yourself in harm’s way on its behalf, or anything else your sense of responsibility tells you.

Some of those actions will be loud and public, others quiet, invisible, never to be known. They are beginning already. And though it is not the bravest form of action, and often takes place far from the frontline, I believe the work of sense-making is among the actions that are called for.

I notice that there is a part of me that would like not to be serious, that would like it to be secretly a bluff, a puffing of the ego, when I say that it feels like there’s a new responsibility landing on the ragtag of thinkers and tinkers and storytellers at the edges, one edge of which I have been part of over these last years. And for sure, this is only one map I’ve been sketching, others will have their own that may or may not overlap.

But the way it looks from here tonight, the people who are meant to know how the world works are out of map, shown to be lost in a way that has not been seen in my lifetime, not in countries like these.

I am thinking of one of the smartest, most thoughtful commentators on the events of this year, whose analyses have helped many of us make sense of what Brexit might mean, the director of the Political Economy Research Centre at Goldsmiths, University of London, Will Davies. In an article for the Washington Post, a week after the referendum, he drew the parallel to the Republican primaries. He too had picked up on the Case-Deaton white death study and the correlation between mortality rates and Trump support.

‘Could it be that, as with the British movement to leave the EU, Trump is channelling a more primal form of despair?’ he asks. But as the article approaches a conclusion, the despair seems to have spread to its author. ‘When a sizeable group of voters has given up on the future altogether… how does a reasonable politician present themselves?’

All of this represents an almost impossible challenge for campaign managers, pollsters and political scientists. The need for candidates to seem ‘natural’ and ‘normal’ is as old as television. Now it seems that they also need to give voice to the private despair of voters for whom collective progress appears a thing of the past. Where no politician is deemed ‘trustworthy,’ many voters are drawn toward the politician who makes no credible pledges in the first place. Of course government policy can continue to help people, and even to restore some sense of collective progress. But for large swaths of British and American society, it seems best not to state as much.

As I read them, these are the words of a person who is running out of map, though one who gets closer than many to seeing how deeply the future is broken, how far the sense of collective progress is gone.

While the victorious political centre of the Clinton and Blair era has gone on insisting that everything is getting better and better, some of the smartest thinkers on the left have recognised the breakdown of the future and responded by setting out to reboot it, to recover the kind of faith in collective progress that made possible the achievements of the better moments of the twentieth century.

If their attempts have struggled to gain traction, one reason may be that the left is better at recognising the economic aspects of what has gone wrong than the cultural aspects, which it tends to ignore or bracket under bigotry. There are great forces of bigotry at work in the world, they will have taken great encouragement from Trump’s election and they need to be fought, as they have been by anti-fascist organising in working class communities, again and again. As a teenager in the northeast of England, my first activism was going out on the streets against the British National Party with Youth Against Racism in Europe. Still, without pretending that they can be neatly disentangled, there are other aspects of what has gone wrong that belong under the heading of culture, besides racism and xenophobia.

In the places where it happens, economic crisis feeds a crisis of meaning, spiralling down into one another, and if we can only see the parts that can be measured, we will miss the depth of what is happening until it shows up as suicide and overdose figures.

Without a grip on this, the left has struggled to give voice to those for whom talk of progress today sounds like a bad joke. And yeah, maybe Bernie could have done it — he’d surely have been a wiser choice for the Democrats this year — but the thing is, we’ll never know. Meanwhile, across the western countries, too often, the only voices that sound like they get the anger, disillusionment and despair belong to those who seek to harness such feelings to a politics of hatred.

This is where I intend to put a good part of my energy in the next while, to the question of what it means if the future is not coming back. How do we disentangle our thinking and our hopes from the cultural logic of progress?For that logic does not have enough room for loss, nor for the kind of deep rethinking that is called for when a culture is in crisis. But that is another story, and a longer one even than this text has become, and I must get up in a few hours’ time to go talk about that story with a conference full of hackers.

On Wednesday morning, the snow was falling hard. Before I finally got to bed, I had given my son breakfast and taken him to kindergarten, pushing his buggy through the snowstorm. Last time we had snow, he was still a baby wrapped inside a pram: now he is fifteen months and discovering everything. After dinner that night, he danced with me and we laughed together like fools.

I want to say that this is also history, though it doesn’t get written down so much: the small joys and gentlenesses, the fragments of peace, time spent caring for our children, or our parents, or our neighbours. These tasks alone are not enough to hold off the darkness, but they are one of the places where we start, one of the models for what it means to take responsibility for the survival of things that matter deeply.

Fifteen months and every day now he is playing with new words in his mouth. I can see the time coming when the words become sentences and questions, when he starts to want the world explained to him.

‘How can I get through it?’ a friend asked.

This was earlier that morning, before the snowstorm.

‘We’ll get through because we have to,’ I wrote, ‘the way we always have, one foot in front of another. Hold those you love tight. Be kind to strangers.’

‘I’m really not looking forward to telling my kid he lives in President Trump’s country,’ another friend wrote.

‘Our kids are going to be the ones who get us through this,’ I told her. ‘That’s how long this journey will take.’

What am I doing here, I wonder now? I don’t even live in America. Though somehow we all live in America, because it fills our ears, spills out of screens and teaches us to dream. But also because we can feel it coming, see the same gaps widening in our own societies, watch the same complacency or helplessness on the faces of the old leaders and the ugly smiles of those who are sure their time is coming.

Everyone who said they knew what they were doing has failed. How badly things turn out now, we can’t say for sure. But there is work to be done.

First published as Issue 11 of Crossed Lines, my occasional email newsletter.