On the desk at which I write there lies a wand. At least, this is how I have thought of it, since the afternoon, five or six years ago, when it came into my hands: thirteen inches of fenland bog oak, turned on a pole lathe, its tip the shape of an acorn.

I’d slept the night at a friend’s house in Peterborough and, before dropping me at the station, he wanted me to see the Green Backyard. Even in the short time I had to walk around the site and chat over a cup of tea, I got why. There’s a particular magic that encircles certain projects, so strong that you can smell it. I think of the Access Space media lab in Sheffield, or the West Norwood Feast street market in south London, owned and run by the local community.

By invoking the idea of ‘magic’, I want to point to a quality which these projects share. At their heart is something that is obvious, yet beyond the grasp of the logic of either the private or the public sector, because their existence would be impossible without the active involvement of people who are doing things freely, for their own reasons, rather than because they have been paid or told to do so. A parallel vocabulary has grown up to cover this kind of activity — its initiates speak of ‘the third sector’, ‘civil society’, ‘social capital’ and so on — but my suggestion is that, while it may have its uses, such language misses much of what people experience as distinctive about places such as Access Space or the Green Backyard. (Nor is it quite covered by the older language of ‘volunteering’.)

I could go further in elaborating this distinctiveness and the way it eludes expression in a formal language — and I would do so by locating this kind of activity within the logic of the commons, as distinguished from the entwined logic of public and private. As Ivan Illich writes of the customary agreements which governed the historical commons of England, ‘It was unwritten law not only because people did not care to write it down, but because what it protected was a reality much too complex to fit into paragraphs.’ This complexity did not present a problem for those involved in commoning — and, as Elinor Ostrom demonstrates conclusively, Garrett Hardin’s much-cited assertion that commoning ends inexorably in tragedy was a crude libel. Rather, it is to those who would govern, manage or exploit from above that the ‘illegibility’ of the commons appears as a problem. In any attempt to simplify the complex human fabric of a commons into a written framework, what Anthony McCann calls ‘the heart of the commons’ is likely to go missing.

This line of argument may go some way to explain the difficulties that ensue when those responsible for such projects find themselves having to deal with systems and institutions whose reality consists of that which can be written down, measured, counted and priced. Yet, in spelling this out, there is a danger that it comes to read as an argument against any attempt at collaboration with the public or private actors with which such projects often find themselves having to coexist, and this too would be a simplification. Instead, in the notes that follow, I want to share a way of thinking about the trickiness of language that has grown out of my own experience of helping to bring such projects to life.

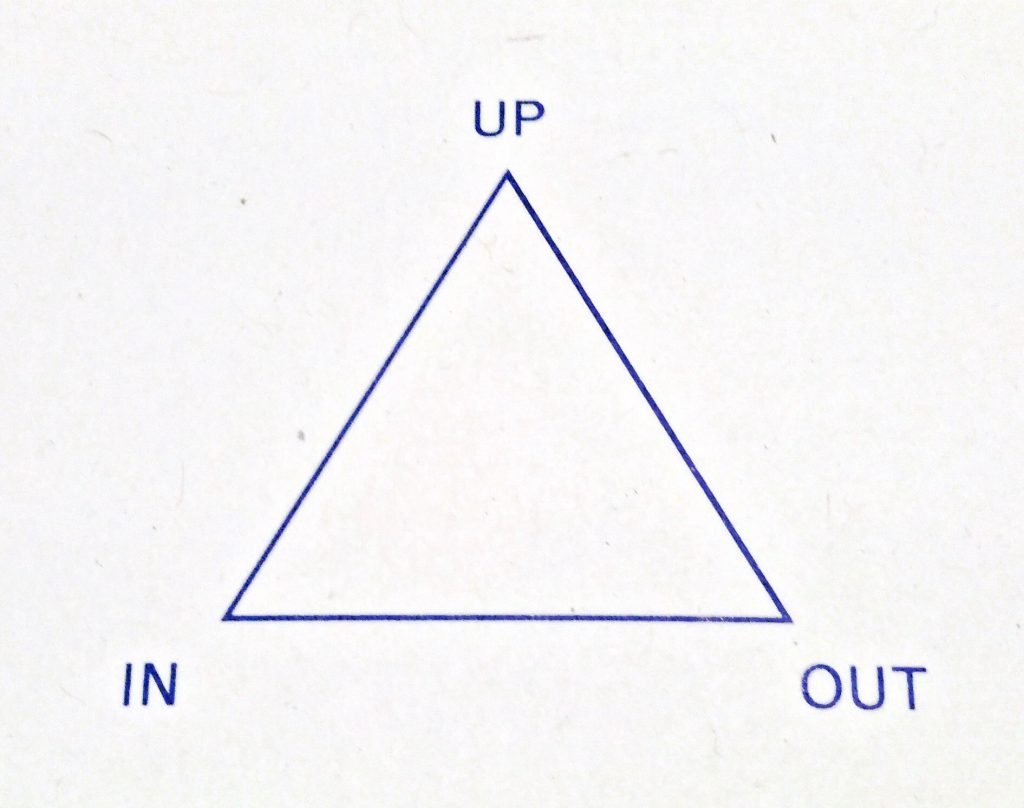

So I take the wand, or whatever it is, and draw a shape in the dust. This is not an authoritative model, only the kind of map that one friend might draw for another on the back of a napkin, trying to pin down an experience that is just starting to make sense.

I have been carrying this model around for a couple of years. It came out of conversations with a friend with whom Anna Björkman and I were beginning a collaboration here in Sweden, and out of Anna’s experiences working with grassroots women’s organisations in Israel and Palestine. We needed a way to make sense of the shifting terms in which we found ourselves talking about the same project. It gave us a shared reference point to make sense of which language was appropriate to which context, how and when to move between them.

It also offers a way of mapping a set of problems that you may have encountered in your own work or in the work of people and organisations with whom you have had dealings.

For example, you might recognise the kind of project which has an Upward language but no Inward language, which appears to have been constructed entirely for the purposes of accessing funding and resources, with no underlying life to it. Whole organisations seem to exist to create such projects, serving little other purpose.

Another situation is the project which has an Inward language but no Outward language. Most likely, this means that the project is not yet realised.

The poet W.B. Yeats — no stranger to magic — once wrote, ‘In dreams begins responsibility’, and this can serve as a motto for the process by which an idea comes to life. At the start, there is a spark: a moment when you see each other’s eyes light up and the conversation quickens, or you catch sight of an opening and turn towards it. A long and indirect journey lies between this and the time when the idea has become something ‘out there’, something you can point to, something people can tell each other about — by which time, the fluidity of dreams has given way to the heaviness of responsibilities, paying bills and filing accounts.

Often, you are some way on in this journey before the project has anything resembling an Outward language, and the words you use to explain it to outsiders may change many times before they settle into shape. The lack of a satisfying Outward language is not a problem to a project that is still making its way into being, though it may cause problems for those involved, if they are asked to explain why they are devoting their time and energy to it.

However, in the absence of an Outward language, be cautious about attempting to explain a project that exists mostly in your dreams and schemes to a neutral audience. The Inward language is like a set of in-jokes: to those involved, it is a web of meaningful connections, but to the uninitiated it is just boring. In the worst case, this hardens into the phenomenon of those ancient mariners who haunt certain kinds of conference, keen to talk you through a PowerPoint deck the length of a Victorian novel which explains their model of the world and how it could be bettered. I don’t doubt that at the root of each such model lies a powerful experience of insight, but I would rather eat your cake before I decide whether I am interested in the recipe, and if you keep trying to feed me recipe after recipe, I may begin to wonder if you actually know your way around an oven.

To get far enough inside another person’s model of the world that you can feel for yourself what it makes possible is a considerable undertaking. Around the projects with which I have been closely involved lies an improvised scaffolding of ideas — chunks of Keith Johnstone’s improvisation theory, Brian Eno’s notion of ‘scenius’, a back of an envelope version of John McKnight’s Asset-Based Community Development, swathes of the work of Ivan Illich, odd lines scavenged from poets, conversations that Anna and I have around the breakfast table — and in any particular project, these will be bound up with the thoughts and experiences of others with whom I am working. If you really want to know about this stuff, as we get to know each other, I’ll map out corners of it with you, rather as I am trying to map out one particular corner in this text. But the projects themselves must stand or fall without the scaffolding, or nothing has been built.

One last case, before we sweep away the dust and the triangle with it.

From time to time, I come across a project which has made the journey to the everyday world of responsibilities without losing sight of the dreams in which it began, which has a lively Outward language and shows signs of an Inward language — not densely scaffolded with footnotes, necessarily, but rich in meaning — and which has reached a point where increased contact with larger institutions and structures is necessary, often because its success makes it no longer possible to operate below the radar.

If such contact is not to end badly, an Upward language is required, and guides are found to help navigate these colder and unfamiliar waters. These guides offer a formal terminology in which to describe the activities of the project, words which carry authority and which offer a legibility that may also contribute to the development of the Inward language, especially if this has tended to rely on the implicit, on things that are understood without even being put into words.

The caution here is twofold. First, the authority of such words should not be treated with too much respect. The knowledge and understanding which those involved in the project already have is what brought the project to life — and while there are expert languages which are good at naming and describing the processes by which things come alive, these languages tend to be sterile in themselves. Make use of them, where they help, but do not treat them as seriously as they seem to want to be treated.

Secondly, guard against the intrusion of the Upward language into the Outward. If it helps with funding applications to deploy words like ‘sustainability’, ‘innovation’, ‘learning platform’, ‘resilience’, ‘impact’ or whatever this year’s keywords are for the structures with which you need to interface, then by all means use them. Just don’t use them when you speak with or write for other human beings.

It is here that Jessie Brennan’s work with the Green Backyard can offer an example. Art has its own tangle of languages, of course, but here the artist takes on the role of the listener, making time to go beyond the first answers that people might give to a survey or a journalistic vox pop, getting closer to the heart of why a project matters to the people who come into contact with it, then drawing out the words that sing to her and giving them voice in new forms. Not every project has the benefit of such a resident, but every project that has come alive has stories and voices like this, and will reward the patience of someone who takes on the role of the listener. This is where you find an Outer language, by listening to the way that people tell each other about what you are doing, looking for the words that seem to travel.

What I remember from that brief visit to the Green Backyard is the web of lives and skills woven together into the project: the farmer who was persuaded to bring his tractor down to plough up part of the site; the offenders coming to work here as part of a community service order, some of whom went on coming back after their sentence was over; the graffiti kids painting boards around the site. The work of weaving together such unexpected combinations into a human fabric is a kind of gentle magic — and it is at its most powerful when grounded in place, as at that patch of former allotments in Peterborough, or the shipyard in Govan that is home to the Galgael Trust, or the acre of ancient ground in the Cheshire countryside where Griselda Garner and others weave together the Blackden Trust.

Such projects do not play on a level field, but on fields that were enclosed generations ago and that are still being enclosed today by those who, like Garrett Hardin, want to insist that only privatisation can secure their future and that the public good is served by the maximisation of the kinds of value that can be reduced to a figure in a spreadsheet. Heartbreaking decisions often get made as a result, and even what looks like success can bring a danger of hollowing out. The land enclosures that climaxed in the 18th century were carried out in the name of ‘improvement’; today, the word would be ‘development’, but the dynamics are much the same. Yet if the value of the commons remains always partly mysterious to systems which can only deal with the legible, so too does their capacity for endurance and the strength which they give to those who live and work with them, and the process of enclosure is never quite as total as its promoters would like us to believe.

First published in Re:Development: Voices, Cyanotypes & Writings from the Green Backyard by Jessie Brennan (Silent Grid, 2016).