You look at what’s happening last night in Sweden. Sweden! Who would believe this? Sweden!

Donald Trump, 18 February 2017

Sweden was long seen as a progressive utopia. Then came waves of immigrants – and the forces of populism at home and abroad.

The New York Times, 10 August 2019

‘If you get a call from the post office, you tell them we’re separating.’

So it’s come to this, I think, as I read the message.

At the end of a long trip back to England, as we sat waiting for the Eurostar check-in, some light-fingered Londoner stole my daypack. The items lost include the mobile phone on which I have my BankID: the digital login that enables access, not only to my Swedish bank account, but to everything from the tax office to the national change of address system. To make matters worse, I’ve also lost my national ID card, and the bank won’t give me a new digital ID without seeing it, and there’s a two-week wait for an appointment to apply for a replacement. Oh yes – and we’re moving into a new apartment the day we get back, so my other half is understandably keen to get at least one of us listed as living at this new address. Keen enough that she’s about to officially declare our relationship over.

‘Can’t you explain the actual situation?’ I message back.

‘This is Sweden,’ she replies. ‘There is no template for that.’

* * *

The Swedish word for immigrant is invandrare, literally ‘in-wanderer’. Like various words in Swedish, it has been subject to critique in recent years: it puts the immigrant in a thankless position, forever the one who is wandering in, never getting to arrive.

Friends who came here from further away, whose names and bodies mark them as ‘other’ in ways beyond my experience, talk about the daily toll of small reminders of their otherness. The questions in job interviews, the glances on the street. The exhaustion of doing everything ‘right’ and knowing it still won’t help.

Don’t get me wrong, then, when I say there’s truth in that word. Even for this white guy from England, spared all the shit my friends put up with, the process of wandering in to Sweden seems endless. Probably it is like this anywhere: I remember a bewildering night in a stand-up club in Dublin, as joke after joke flew over my head, missing the references everyone else was getting. Seven years in, while my Swedish is somewhat fluent, I still can’t do half the things I’m used to being able to do with language, and even if I reach that point, I know life will continue to be full of jokes that I don’t get.

Still, for all its foolishness, the situation of the perpetual half-outsider can bring with it certain gifts. You can find yourself in the role of interpreter, the person who notices details so obvious to everyone who grew up here that it takes a stranger’s eye to see them.

Or maybe it’s just that, when you’ve been living in another country for a while, friends elsewhere turn to you when they want to understand what’s happening there.

* * *

An email arrives from a friend in New York with a link to an article in his local newspaper, a New York Times feature headlined ‘The Global Machine Behind the Rise of Far-Right Nationalism’.

It’s a story about Sweden and the rest of the world. It’s about the Sweden Democrats, the anti-immigrant party with neo-Nazi roots that took 62 of the 349 seats in the Swedish parliament at last year’s general election. It’s about the way political forces elsewhere seize on stories about Sweden and immigration – and it’s an examination of the role of those external forces in the rise of the Sweden Democrats.

The Times reports that it has uncovered ‘an international disinformation machine’ with roots in ‘Vladimir V. Putin’s Russia and the American far right’, peddling a ‘distorted view of Sweden’ and seeking to influence elections here:

The central target of these manipulations from abroad – and the chief instrument of the Swedish nationalists’ success – is the country’s increasingly popular, and virulently anti-immigrant, digital echo chamber.

The implication is that the Sweden Democrats’ electoral success reflects the influence of those manipulations from abroad, and the reader is left to draw the parallels to American politics.

‘How much of this is true, according to you?’ my friend wants to know.

I start writing back to him and then I realise that I’m writing an essay – an essay that’s been coming a long time, about the country that has become my home and the role it plays in the collective imagination of millions of people who have never been here.

* * *

‘Welcome to the warm south of Scandinavia!’ declared a poster during the 2014 referendum campaign, a playful invocation of Scotland’s future, drawing on the long tradition of locating utopia at the top of the map of Europe.

It’s hard to think of a part of the world more closely coupled to a concept: the two best recent English-language books on Sweden are Andrew Brown’s Fishing in Utopia and Dominic Hinde’s A Utopia Like Any Other.

Hinde’s book starts in Scotland, reflecting on the way the Nordic countries in general and Sweden in particular feature in the political imaginary of the independence movement, but he’s quick to point out how much wider and further back this goes. As far back as Mary Wollstonecraft’s letters from Scandinavia which caught the imagination of readers in the 1790s. Even further, you might say, to Ancient Greece, when Pindar could write of the Hyperboreans, the fabled people of the far north:

They wreathe their hair with golden laurel branches and revel joyfully.

No sickness or ruinous old age is mixed into that sacred race;

without toil or battles they live, without fear of Nemesis.

The modern version of this myth-making begins with a 1930s bestseller, Sweden: The Middle Way, by the American journalist Marquis Childs, which introduced readers to a society that had found a golden path between capitalism and communism. ‘Eighty years on,’ as Hinde observes, ‘the narrative is remarkably similar, even if the world around has changed beyond all recognition.’

It was this narrative that David Cameron was able to draw on – in his pre-austerity, husky-hugging days – when he took up the Swedish model of ‘free schools’. Never mind that the policy was actually a landmark of Sweden’s particular strain of neoliberalism, or that the only other country to go down the route of allowing profit-making companies to run its state schools was Pinochet’s Chile. Back when the Tories at Westminster were still interested in detoxifying their brand, the connotations of Swedishness were strong enough to make this part of Cameron’s strategy of flirting with Guardian readers.

The classic case, though, is the story about Sweden ‘moving to a six-hour working day’. Back in the days when I still went on Twitter, I remember gently chiding my mate Pat Kane for circulating this one, but he was hardly alone. Newspapers from The Independent to the Sydney Morning Herald ran with it, announcing it as though it were a national policy, rather than a short-lived experiment at a couple of workplaces in Gothenburg. Because this is the kind of thing lots of people are longing to believe about Sweden.

So here’s the first part to get straight, if we’re going to talk about a ‘distorted view of Sweden’: it doesn’t start with Donald Trump and Fox News and the Gatestone Institute and the Russian troll factories. When it comes to making absurd exaggerations about this country to suit their beliefs, they are latecomers. If Sweden occupies an outsized position in the dystopian geography of the nativist right, this is derivative, a sacrilegious inversion of the role it has held for generations in the belief system of their progressive opponents.

It seemed harmless enough, a few years back, when no one talked about ‘fake news’ – but actually, what’s the difference between taking a small local experiment and blowing it up into a story about a whole country switching to a six-hour day, and taking a few local incidents involving immigrants and blowing these up into a story about a whole country where law and order is breaking down? The content is different, sure, and the consequences darker, but the basic pattern is the same.

* * *

A year after I moved to Stockholm, there were riots, though the first I heard about it was the messages from concerned friends elsewhere. In London, two summers earlier, there had been a genuine sense of danger, of a city on the edge of chaos. But Stockholm isn’t London, it’s more like Paris: a historic inner city, affluent and white as hell, and then a ring of concrete suburbs where the others live.

In one of those suburbs, the police shot and killed a man who had been seen on his balcony carrying a knife. There were protests in the days that followed, and then a few nights of trouble, with stone-throwing and cars set alight. It wasn’t nothing, and it could have got worse – at one point, police stopped a convoy of thirty vehicles, far-right extremists heading for where the trouble was, armed and looking for a fight – but if the same scenes had played out in the Parisian banlieues, it’s hard to imagine them making international headlines.

DOG BITES MAN is not a story, they tell you in journalism school. MAN BITES DOG is a story. By this logic, it turns out that it’s not just the nativist right who are quick to jump on tales of trouble in the social democratic paradise, it’s also the same mainstream news industry responsible for spreading fantasies about the six-hour day.

This tendency has coloured the reporting of the entry of the far right into Swedish parliamentary politics. In 2016, I found myself pulling up Jon Henley of the Guardian over a news report that presented the Sweden Democrats as ‘now Sweden’s largest party’. Yes, a handful of outlying opinion polls that year had put them in first place, but the rolling average always had them behind the traditional larger parties of left and right. Now, that might seem like a detail, when set against all that the rise of such a party signifies – and I swear, I don’t actually spend my days fact-checking English-language commentators on their general knowledge of Sweden – but it’s another example of an eagerness to overstate what’s happening in this country, an eagerness that gets in the way of what we could learn together here, the clues that we might find in the particular experiences of this large, sparsely populated country at the top of Europe.

It’s there in that New York Times feature, too. Read the whole thing and you’ll learn about the national socialist roots of the Sweden Democrats, how their ‘right-wing populism has taken hold’ in a country ‘long seen as a progressive utopia’, but the one thing you won’t learn is that their performance in last year’s general election fell well short of their hopes and others’ fears. Four years earlier, they had beaten the opinion polls and more than doubled their vote, reaching 12.9% – and during the last weeks of this election campaign, many of us expected them to double their showing once more. Against this background, alarming as it remains in its own right, the 17.5% the party achieved on polling day represents a loss of momentum.

The omission of this context from the Times article matters, because it weakens the argument the article is built around. If what lies ‘beneath the surface of what is happening in Sweden’ is ‘an international disinformation machine’ – if this is the engine powering the rise of right-wing populism, here and elsewhere – then surely the Swedish far right should have been gaining momentum like never before? For who could deny that these past few years have been the historical moment in which digital media and nativist politics fused into a global phenomenon?

We’ll come back to this glitch in the timeline and what gets left out in the eagerness to centre the story on international networks and external manipulation, but there’s another element in the Times article that is worth lingering over, and that’s the particularly dark roots of Sweden’s right-wing populists. It’s pretty standard for a European democracy today to have an anti-immigrant political party polling between 15 and 20%, but it’s rarer for that party to have its origins so directly in the milieu of uniform-wearing neo-Nazis and white supremacists.

The way the Times tells it, the breakthrough of such a party in Sweden is all the more remarkable, given the country’s social democratic heritage, a political culture that made voters resistant to the Sweden Democrats’ earlier and more explicitly racist rhetoric. The rosy utopian picture of Swedish social democracy strikes again, I think to myself, and I start to see how much ground this essay needs to cover.

Maybe I can get there by looking past the stories projected onto this country by its admirers and detractors, to the stories Sweden likes to tell itself?

* * *

There are many shades of culture shock. In my mid-twenties, I spent half a year in the far west of China. For the first two months, I had to carry a card with my address to show to taxi drivers because I couldn’t produce a recognisable imitation of the six syllables that would tell them how to take me home. Everything about the world in which I was immersed seemed extraordinary and the shock of difference was psychedelic, exhilarating, some days overwhelming.

When I started learning Swedish, the main problem was getting anyone to speak it back to me: ordering in a café, I’d stumble through a sentence and the guy behind the counter would respond in flawless English. Coming from England to Sweden, the culture shock is subtle and catches you off-guard, like when you go down stairs in the dark and there’s one step more than you’d reckoned on there being: a series of these small jarring encounters with the gap between your expectations and those of everyone around you.

Reading about Swedish history, I was caught off-guard by the concept of the Stormaktstid, the ‘Great Power Time’. It wasn’t just how ignorant I’d been of the imperial adventures of the Swedish 17th century, when the territory ruled from Stockholm stretched from the Atlantic to the far side of the Baltic and the north coast of Germany; it was the surprise of encountering a country that can speak matter-of-factly about its great power status as something that lies a long way in the past. Needless to say, England has no equivalent to the concept of the Stormaktstid, no common language in which to acknowledge the waning of its global standing, and I’m tempted to see the act of political arson that is Brexit as stemming from this lack.

The last remnant of Sweden’s greater territorial ambitions was relinquished in 1905 with the peaceful dissolution of the union of the crowns of Sweden and Norway. To travel between these countries today, to listen to conversations in which their two languages blend, is to catch a glimpse of how it might go in Britain, a century or so down the line from the dissolution of another United Kingdom.

Yet this vision of a peaceable endgame of history, relieved of the burdens of geopolitical self-importance, is complicated by another story of greatness that Sweden likes to tell itself. It was the Swedish diplomat Pierre Schori who coined the phrase en moralisk stormakt, ‘a moral superpower’, to describe the role his country had assumed in the 20th century. The phrase was meant with pride and it marks the point at which the external projections of modern Sweden as a utopia, originating with Childs in the 1930s, loop into the country’s self-narration, producing a sense of exceptionalism strangely parallel to America’s story of itself as ‘a city upon a hill’, a beacon of light in a dark world. The Swedish version of this story is hardly less shadowed.

A moral superpower may not go around starting wars, but in Sweden’s case, it seems happy enough to profit from the sale of weapons. It’s not just that Alfred Nobel endowed his peace prize from the wealth he made in developing modern explosives, or that this country was responsible for the invention of everything from the landmine to the machine gun; it’s that Sweden remains one of the world’s great arms manufacturers to this day. In per capita terms, its exports of military hardware are exceeded only by Russia and Israel.

There’s a book called Ambassadors of Realpolitik. It’s about Sweden’s role during the Cold War, but the country’s military-industrial pragmatism continues to collide periodically with its idealised self-image. In 2015, a red-green minority government, which had come to power pledging a ‘feminist foreign policy’, found itself in the kind of fix that Robin Cook would have recognised. The foreign secretary Margot Wallström had been outspoken in her criticism of human rights abuses in Saudi Arabia. Now a longstanding arms treaty with the kingdom was up for renewal. Eventually, after much-reported cabinet splits, and in the face of opposition from unions and business leaders, the treaty was revoked. It was a sign that there remains life in the ideal of the moral superpower, yet in the broader scheme of things, such a gesture hardly made a dent in Sweden’s role as a global arms dealer.

Schori’s phrase still surfaces now and then in newspaper debate articles, but there is a suspicion in today’s Sweden that the time of being a great moral power has also passed into history. In 2006, the erudite comedian Fredrik Lindström – Sweden’s answer to Stephen Fry – presented a prizewinning documentary series about the national psyche called The World’s Most Modern Country. It’s a title that plays on the stories of Swedish exceptionalism and the concrete achievements of its 20th century modernisation, but also on the sense that ‘modernity’ itself is now old-fashioned. Lindström’s artful monologues of self-doubt, the montages in which he is edited into archive footage, and the studio set reminiscent of the one in which David Frost interviewed Olof Palme made the series a study in postmodernism, Swedish style. A couple of years later, the historian Jenny Andersson published a book that tracks the decline of social democracy in Sweden and the rise of a nostalgia for the era of high modernity; its title translates as When the Future Already Happened.

To this picture of early 21st-century Sweden, adrift in the aftermath of its own modernity, having lost and found and lost again its sense of greatness, let me add one more element that jars against my English expectations, and that is the phenomenon of a society in which the Social Democrats have truly been the establishment, hegemonic and replete with a deep-seated sense of entitlement. This may have its equivalents in the experience of local government in certain cities around the UK, but at Westminster, even when Labour has been in office, it has rarely felt itself to be in power. There are times when the contrast can feel like passing through the looking glass.

One small example: a few years ago, I was brought in to moderate a three-day event with a network of grassroots cultural projects from around Europe. Our hosts were an organisation based in one of those concrete outer suburbs of Stockholm, and over our time together I noticed a gap between their mindset and the other partners who came from countries to the south and east. The Swedes seemed quite sincere in their enthusiasm for a rhetoric of creative urban entrepreneurship that stank of neoliberal horseshit to the rest of us. Afterwards, it struck me: perhaps these phrases that rang so hollow to us could sound like a vehicle for change, if you grew up with the hegemony and homogeneity and complacency of a society so strongly shaped by one political vision?

* * *

The New York Times article locates the turn of the Sweden Democrats fortunes in their shift from a rhetoric of outright white nationalism to a defence of ‘the social-welfare heart of the Swedish state’. Where once it sought to deport immigrants as a threat to racial purity, the party now argues for the need to close the borders if the Swedish model is to be saved. At the centre of this model, the Times explains, is ‘the grand egalitarian idea of the “folkhemmet,” or people’s home, in which the country is a family and its citizens take care of one another.’ Though only, it should be added, through the impersonal vehicle of the state.

In this telling, the far right has taken the social democratic utopia hostage, convincing its voters they can only hang on to their benefits and pre-schools and care homes if they keep the foreigners out. What complicates matters is that the concept of the ‘people’s home’ was itself lifted by the Social Democrats from the language of the radical right in the 1920s.

If Marquis Childs’ book was the ur-text for the utopian image of Swedish social democracy in the outside world, the equivalent position within Sweden’s own political imaginary is held by the folkhemstalet, a speech given by Per Albin Hansson on 18 January 1928. In it, he held up a vision of the good society as ‘a good family’, a home in which there are no favourites and no stepchildren, and he set out the scale of the work that lay ahead to realise this vision. Four years later, Hansson became the first of the great Social Democrat prime ministers, inaugurating what would prove to be four decades of almost uninterrupted rule, time enough to go about building the people’s home.

The choice of language in that speech was significant: on previous occasions, Hansson had spoken of the medborgarhemmet, ‘the citizen’s home’, a cooler and more clearly democratic term, but now he deliberately took up an expression associated with the radical conservative thinker Rudolf Kjellén. This was the same language whose potency was making itself felt in Germany in those years: the ‘folk’ in folkhemmet is a close cousin of the Volk of the National Socialists.

The Swedish writer Katrine Kielos describes this move as a masterpiece of political reframing, capturing the rhetorical ground of one’s opponents. Writing in 2012, she could draw a comparison to Ed Miliband’s – in hindsight, rather less successful – attempt to steal the ‘one nation’ rhetoric of Toryism. Yet this is a little too comfortable a take, steering us away from the shadow side of the project which Hansson launched.

Few would dispute that the building of the people’s home in Sweden was a feat of social engineering on a grand scale. Chief among its architects were the couple Alva and Gunnar Myrdal, among whose prolific and influential output was the 1934 book, Crisis in the Population Question, which argued for strict laws to preserve the quality of the human ‘breeding stock’. An enthusiasm for eugenics was not peculiar to social democratic thinkers, nor to Sweden; rather, it was commonplace among intellectuals, progressive and conservative, during the interwar period. However, such concerns were more deeply rooted in Sweden than elsewhere and their hold on Swedish institutions more enduring.

In 1921, the Swedish parliament approved the creation of the Institute of Racial Biology at the University of Uppsala, the first state-funded centre for the study of eugenics in the world. Its founding director, Herman Lundborg, led a research programme that involved measuring the skulls and photographing the bodies of more than a hundred thousand Swedes, in pursuit of a more rigorous statistical basis for policies of ‘racial hygiene’. To Lundborg and his contemporaries, this project of racial categorisation was simply an extension of the work begun in Uppsala two centuries before by Carl Linnaeus, who set out to organise the diversity of the living world into a hierarchical taxonomy; in its original form, the Linnaean system included four subspecies of Homo sapiens, defined according to their skin colour. Despite the difficulty Lundborg had in drawing any meaningful statistical conclusions from the measurements his team had made, he received international recognition for his work, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Heidelberg in 1936.

When war came three years later, Sweden declared itself neutral. The country was in no position to defend itself and had no desire to end up under occupation, like its neighbours to the west. So its neutrality was born of pragmatism and had the quality of a weathervane: when the war was going well for Germany, Sweden kept it supplied with iron ore and timber, transporting its soldiers home on leave from occupied Norway, or even en masse to the Finnish border to launch an attack on the Soviets. Later, it would find ways to be of use to the Allies, in their turn.

This policy had its consequences for Sweden in the post-war world. While much of Europe lay in ruins, Sweden’s cities and industrial plant remained intact, its economy unburdened by war debts, and so the conditions for its economic take-off in the years that followed were closer to those of the United States than to any of the combatant countries of its own continent. The sheer prosperity of Sweden in the post-war decades, which contributed to the sheen of its utopian image, owed much to its peculiar experience of the war and its aftermath. My hunch is that the deep love for ’50s Americana in Swedish working class culture carries an echo of this period; the whale-sized tail-fin cars that gather to cruise the downtown streets of provincial towns are relics of an era of rising and broadly shared prosperity on both sides of the Atlantic.

The other legacy of Sweden’s World War II neutrality was a lack of reflection. With a few exceptions – most famously, the diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who saved tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust – the Swedes seemed to have no wartime heroes, and no real villains. Whilst public opinion in the 1930s had been favourable to much of what was going on in Hitler’s Germany, attempts to launch a national socialist movement in Sweden never got much traction. There was not much soul-searching to be done, nor much moral capital to be gained from dwelling on the events of those years.

Perhaps this explains the persistence of policies and intellectual currents which would not have found a place in the mainstream of other western European societies, more deeply scarred by the legacy of Nazism and the cost of its defeat. The Institute of Racial Biology at Uppsala carried on under that name until 1958. The policies of racial hygiene it was set up to support went on still longer: into the 1970s, the Swedish state was still carrying out the forced sterilisation of groups including Roma and indigenous Sami women. This went on through the high years of social democracy, when Sweden was, by its own estimation and that of many others, ‘the world’s most modern country’.

It is sometimes said rather glibly that the success of social democracy in the Nordic countries was dependent on the ethnic and cultural homogeneity of these societies, as though it were easier to form a social contract of reciprocity with people who have the same colour hair and eyes. Whether or not there is any truth in this, there is a structural level on which the logic of the social democratic state implies exclusion. Whether you call it ‘the people’s home’ or ‘the citizen’s home’, the sheltering roof is built on top of walls. It offers a set of entitlements to those who hold the right papers. There are always rules that specify who qualifies, geographic and bureaucratic borders that mark the bounds of its generosity. While the moral imagination and internationalist commitments of a social democratic movement may lean away from this logic, that only puts it in the trap described by George Orwell in his essay on Kipling, written in 1942:

All the left-wing parties in the highly industrialised countries are at bottom a sham, because they make it their business to fight against something which they do not really wish to destroy. They have internationalist aims, and at the same time they struggle to keep up a standard of life with which those aims are incompatible. We all live by robbing Asiatic coolies, and those of us who are ‘enlightened’ all maintain that those coolies ought to be set free; but our standard of living, and hence our ‘enlightenment’, demands that the robbery shall continue.

By the late 1940s, the United States had launched the narrative of international development, whose genius is to locate Orwell’s ‘Asiatic coolies’ no longer as our contemporaries and servants, but as our followers along a chronological path that will lead them to a destination embodied in the prosperity of the western middle classes. New modes of globalisation took the place of crude colonialism and Sweden has furnished the development project with some of its most passionate and sincere advocates, not least the late Hans Rosling.

For Swedish men of Rosling’s generation, the experience of the post-war boom felt like an absolute validation of the development narrative, while the failure of Sweden’s early attempts at establishing African and North American colonies has lent the country a sense of innocence, compared to the ghosts of empire that haunt the photo albums of Europe’s other great powers. The 18th century nobleman, Axel Oxenstierna, got closer to the truth when he declared, ‘We have an India of our own!’, his enthusiasm sparked by the promise of mineral wealth in the Sami territories of the north, whose exploitation fuels the Swedish economy to this day. Meanwhile, the net flow of resources into this country and the ecological footprint of its consumers, closer to the American than the European average, mark it as a beneficiary of a system that still resembles the colonial arrangements Orwell had in mind, and his charge of hypocrisy still finds a target in a country that can pride itself on 200 years of peace while selling arms around the world.

To draw out the contradictions within the social democratic project, bound up as it is with Sweden’s story of itself, is not to indulge in lazy relativism, to tar the party of the folkhemmet with the same brush as the Sweden Democrats. I’ve heard colleagues speak of their children being spat on for the colour of their skin. The chain of white supremacist terror attacks around the world in recent months, the latest just across the border in Norway, is a reminder of how much worse all this can get. Between the two political parties, there is no doubt whose activists have fought against racism in recent decades and whose have fuelled it.

My point is not to downplay the darkness of the Sweden Democrats, but to recognise it as not simply alien, an external force hijacking the heritage of the Swedish model, but as drawing on something internal to that model, latent within the shadows of social democracy. If there is truth in such a reading, then it calls for a process of reflection that doesn’t stop at moral condemnation of the nativist right.

* * *

It would have been the spring of 2014, the Euro elections, the first time my Swedish was good enough to read the party literature landing in our mailbox. What struck me when I picked up the leaflet from the Sweden Democrats was that it named the day-jobs of their lead candidates, a care worker and a truck driver. The message could hardly have been clearer: we are the party of the low paid and the low status, those at the bottom of the ladder of economic or cultural capital.

In 1989, the sociologist Göran Therborn was the sole Swedish contributor to New Times, the influential book-length collection from the editors of Marxism Today, rethinking the role of the left after a decade of Thatcherism. Therborn’s essay introduced his British readers to the concept of ‘the two-thirds society’, a dystopian projection of the socio-economic trajectory of post-industrial Europe, in which a third of the population find themselves locked out of a prosperity which increasingly goes to those with higher levels of technological and cultural literacy.

At the start of the 1990s, Sweden was hit by its worst economic crisis of the modern era. The literary critic Jonas Thente recalls the nightly news reports in which laid-off workers trooped out of the factory gates for the last time in small towns across the country. While economic growth returned with time, the background rate of unemployment remained higher and in the decades that followed, Sweden has distinguished itself by having the fastest growing inequality of any OECD country. The two-thirds society became a reality, Thente observes, and yet somewhere along the way, we stopped talking about it.

It’s true at least of Thente’s colleagues in the ‘cultural debate’ pages of the Swedish press, who do much to set the agenda of the public conversation, that they have seemed happier to write about gender, racism, LGBTQ and environmental questions than to touch on the themes of class and economic inequality. One particularly Swedish manifestation of this is the phenomenon of normkritik, the critique of social norms. At its best, this involves the unsettling of unexamined assumptions, what a librarian friend of ours calls ‘norm curiosity’: I remember a powerful session with the Swedish-Kurdish comedian Özz Nûjen at the theatre where I worked, as he mixed laughter with painful insight into everyday racism, challenging us to consider how this played out in our own professional environment. It can also slide into something more didactic, less curious, a kind of ‘norm-replacement therapy’ in which we are taught how we ought to be thinking.

But given the acute, at times neurotic sensitivity to the policing of norms in the Swedish cultural sector, the uncritical persistence of one particular norm is striking. In the long dry summer of 2017, as wildfires burned out of control in many parts of the country, I listened in disbelief to a pair of young comedians from Stockholm on national radio as they giggled about how stupid the countryside people are and why they don’t just move to the city, instead of living out in the sticks and waiting for their houses to burn down. Maybe it’s another of the jokes I just don’t get, but it can seem as though the one kind of prejudice that is still welcome in polite Swedish society is prejudice against the inhabitants of the small towns and scattered rural communities that make up Sweden’s flyover country.

It’s a tendency Andrew Brown picks up on, in one of the later chapters of Fishing In Utopia, when he returns to Sweden in the early 2000s, a quarter of a century after he had lived here. In a prosperous middle-class neighbourhood of Gothenburg, he calls on his ex-wife and her current husband, a university professor, and they get to talking about the two-thirds society:

They felt pity for the poor and for the immigrants, but for the people who stayed behind in the small towns of the interior, they felt a rather superstitious contempt, as if their bad luck might rub off on everyone else.

‘We should just close down the whole of the countryside,’ his ex-wife declares, with a sudden vehemence. He wonders if she is remembering the small town where she lived when they first met.

Urbanisation is still a recent and ongoing phenomenon in Sweden. Writing about her experiences making a film here in the late ’60s, Susan Sontag notes that people would often attribute ‘the awkwardness and flatness of their urban life’ to habits brought with them from the farms and the backwoods: ‘most of the people in Stockholm (I’m told) still remember the forest’. So perhaps the exception that seems to be made for this one form of prejudice stems from a lingering assumption that it is somehow self-directed.

The era of widening inequality that followed the crisis of the early 1990s has also been the era of Swedish neoliberalism. Those profit-making ‘free schools’ were introduced under a one-term coalition government of the centre right, but continued with the support of the Social Democrat prime minister Göran Persson, who embraced Tony Blair and Bill Clinton’s ‘Third Way’, with its echoes of the old story of Sweden’s ‘Middle Way’. Successive governments from both sides of the longstanding block divide went on to oversee the increasing agency of the private sector and the profit motive in shaping Swedish society, a process which accelerated after 2006, when the Alliance for Sweden, made up of four parties of the centre-right, achieved an unprecedented two consecutive terms in government. In our research for a workshop in Gothenburg a couple of years ago, my colleagues from the Dutch architecture duo STEALTH.unltd were startled to discover an official website on which the city authorities pitched themselves to international developers at the MIPIM global real estate fair by promoting Gothenburg’s ‘tax-haven’ rates for companies.

What is distinctive about Swedish-style neoliberalism is not simply that parts of the old social democratic model remain in place, but the way that widening inequality twists that model. The universal childcare on offer through the pre-school system is a remarkable support for working parents, but the generous bank of parental leave – paid at up to 80% of your usual earnings and available to be drawn on any time until the child turns twelve – benefits the middle classes most. It’s what meant that our family could make a three-month trip to England this summer, but much as it contributes to my quality of life, I can’t pretend not to know that this system is of less use to a low-paid care worker who needs everything she earns to pay the bills. Owen Hatherley sums it up rather well: ‘in Sweden, social democracy was only abandoned for the poor.’

Three decades on, the predictions of Göran Therborn and his comrades have mostly been born out. Twenty-first century Sweden has become a society of insiders and outsiders, the pattern repeated twice-over: on an urban scale, where immigrants find themselves concentrated in the concrete outer suburbs, and then on the national scale, where the fast-growing urban centres do little to disguise their disdain for the people of the declining small towns and countryside. What made the prospect of the two-thirds society so vicious was that representative democracy would provide little incentive for the established parties to attend to the situation of the excluded third. Into this void has come a party which takes the loss, disorientation and disaffection of one group of outsiders and channels it into a suspicion and barely-disguised hatred of another group.

* * *

In the spring of 2013, I enrolled in Swedish for Immigrants, the basic language programme offered free to all newcomers to this country. That autumn, we moved from Stockholm to Västerås, an engineering city on the shore of Lake Mälaren, an hour’s train ride west of the capital, so it was here that I took my SFI exams. I’d learned how to be an immigrant and I had the certificate to prove it. My Swedish was coming along OK, too. One of my classmates, an exiled Iranian journalist, told me about a follow-on course she had signed up for, intended as a fast-track for professionally educated immigrants, to speed our integration into a society in need of our skills. I went to the job centre and asked them to sign me up, too. Only when I got there on day one did I discover that the course was intended for non-European migrants only, and I had been admitted due to an administrative error. The course leaders didn’t seem too troubled, though, and they let me stay.

In the ordinary course of adult life, few things match the helplessness you experience when starting out in a new language. In those classrooms, in my mid-thirties, I relived the childhood experience of being in a teacher’s hands, for better and sometimes worse. But among my classmates, this helplessness had a certain levelling effect, however different the situations that waited for us outside school.

Many of those I studied alongside had made unimaginable journeys, taken risks and endured humiliations that I hope I will never have to face. The largest group were young men and families who had been part of the early exodus from Syria as the optimism of the Arab Spring gave way to bloody chaos. As often as not, they had wound up in Sweden by chance.

One friend described how, after months in Greece, he got himself smuggled to Spain, where he stood at Madrid airport, trying to get a flight to Munich where he had family, except the only flight he could get a seat on that night was to Stockholm. He took it, planning to lie his way through immigration, to travel south and seek asylum in Germany; instead, he was questioned, fingerprinted and put into the Swedish system, the course of his life turning on that choice of an airline ticket.

Another Syrian guy I got to know had been studying in Tripoli when the Gaddafi regime fell, spent months hiding from gunmen, only to find by the time he escaped that his home country was unravelling into a civil war of its own. His parents had fled to Germany and he managed to join them there, but they fell out furiously over his father’s support for the resistance, and two days later he had left. Now, alone and deeply traumatised, he would sit in class, scrolling through video clips of street battles and explosions.

In all the years I lived in England, I could count the people I knew who had been refugees on the fingers of one hand. Now, as I wandered into a life in Sweden, the first friends I made were these people I sat next to at school. While some were clearly broken by what they had lived through, what struck me mostly was their resilience. I began to notice a difference, though, between those who had families or faith communities to anchor them in these new surroundings and those who had come alone, who would spend their weekends counting the hours until we were back at our desks. That was when we started the Saturday fika club. It helped that Anna, my partner, had lived in Alexandria, working with children’s literature across the Middle East, and later with grassroots women’s groups in Palestine and Israel. This tall blond Swede who spoke street Arabic with an Egyptian accent won a lot of hearts.

Fika is a Swedish institution: a pause for coffee, traditionally accompanied by cinnamon buns or ‘seven sorts of biscuit’, marking a space of sociable conversation in a culture otherwise characterised by reserve. Our teachers tried to instil in us a sense of its importance: when you get a job in a Swedish workplace, they would say, it’s very important that you join your colleagues in the fika room at break-time. So on Saturdays, Anna and I would bake and we’d invite my classmates and her workmates over for the afternoon to hang out and drink coffee and talk Swedish. This went on for a couple of years, long after the course itself was over.

One other memory sticks with me from that period. It must have been early in the second course I took. The class had been broken up into workgroups of five or six, each group allocated some feature of the city’s heritage. We were sent out to research it and then prepare a presentation. My group was given the castle, a twelfth-century fortress by the river mouth, remade so extensively in later generations, you would hardly think it medieval. I threw myself into this eagerly, trying to play the good student, but my colleagues showed less enthusiasm. Finally, one of the women in the group turned to me.

‘Maybe to you this building seems old,’ she said, ‘but we come from a city that has existed for 8,000 years. To us, this is not so impressive.’ She didn’t go on to say that, here they were, treated as barbarians, in a part of the world that had still been in the Stone Age when their ancestors were laying the foundations of what we like to call civilisation.

* * *

I look at the numbers from the Migration Service and try to hold in mind the stories they represent: the journeys, the losses, the humiliations, the plans put on hold, the persistence, the stubborn rebuilding of lives under the circumstances of displacement. It was the autumn of 2015 when the numbers really took off, the nightly news leading on images of a drowned child, desperate encampments at Balkan border posts, crowds walking along the sides of motorways. These scenes were met with an awakening of conscience, a mobilisation of support, with welcome stalls at railway stations and networks collecting supplies for new arrivals. At the theatre, it was announced that we could each put an hour a week of our work time towards volunteering as part of this effort.

That winter, I travelled to a conference in Estonia. In a Tallinn beer hall, I sat up talking late into the evening with Kilian Kleinschmidt, who had recently quit the UNHCR and was advising the governments of Austria and Germany on how to respond to the crisis. ‘Of course,’ he said, ‘there is no reason why this should be a crisis for Europe.’ One million people arriving in a continent of 500 million, in some of the richest countries in the world – that this should strain our systems or our capacity to respond told us something troubling about ourselves.

I’d read about Kleinschmidt’s work as Senior Field Commander at the Zaatari camp in Jordan, where he declared himself the mayor and the refugee camp a city whose residents were capable of organising to meet their own needs. His courage, his ability to build relationships and to generate publicity made Zaatari a success story, but it didn’t surprise me to learn that it had also marked the end of his career within the structures of a UN institution.

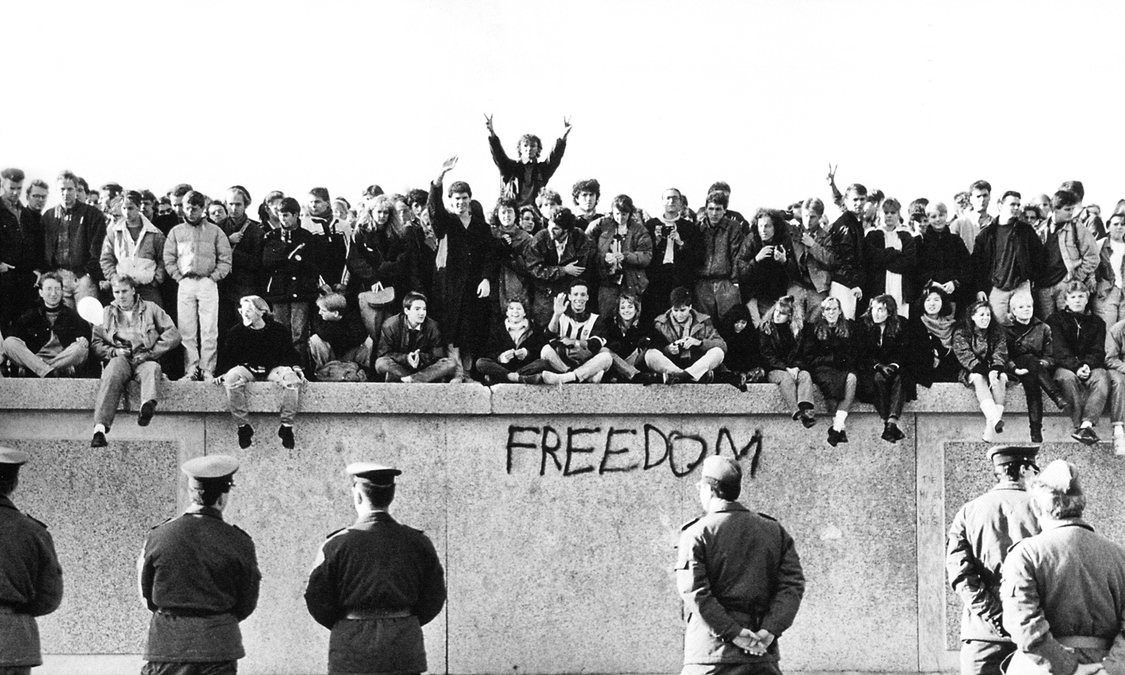

Now, he spoke of the agency of the million people who had brought their desperation to Europe, commanding an attention which decades of professional communications work by NGOs and international bodies had failed to deliver. By coming here, they had revealed the gap between Europe’s story of itself and the realities that underlay that story: they were showing us how fractured our supposedly integrated continent remains, and how close to the surface were the ghosts of the politics of hate that European integration was meant to have buried.

He talked about the threat of the far right – and then, he said, on the other hand, you have these people who want to keep refugees like pet guinea pigs. ‘You see it on Facebook: “How sweet, my Syrian was shopping and now he’s cooking for me!” Well, this is no good, either: a sentimental paternalism that makes victims of people all over again.’

The next morning, at the opening session of the conference, I found myself sitting next to the Estonian culture minister. Over breakfast, a friend had been explaining the country’s ‘e-residency’ scheme, which allows individuals anywhere in the world to register for an ID card and set up a business that is legally based in Estonia. ‘I hear you have 5,000 e-residents signed up already,’ I said to the minister. He smiled and started to tell me about the scheme’s attractions for entrepreneurs. ‘I’m interested in how a system like this could work for displaced or stateless people,’ I said. His smile froze and he suddenly found an urgent need to speak to someone in the row behind us. Later, I learned that, just that morning, after months of tense political debate, the government had announced the arrival of the first group of refugees under the EU’s resettlement programme. There were seven of them.

In late November 2015, Sweden’s deputy prime minister, Åsa Romson of the Green party, broke into tears at a press conference, as she stood alongside the Social Democrat prime minister Stefan Löfven to announce the reversal of their government’s previous policy on immigration. In order to give the system a ‘breathing space’, Löfven explained, the right to permanent residency for refugees was being suspended, the right of family reunification restricted and border controls reintroduced on a regular basis between Sweden and Denmark. These were temporary measures, to apply for the next three years. This was a terrible decision, Romson added, but her party had chosen to remain in the government to avoid decisions even more terrible being taken.

By that point, the numbers of people arriving in Sweden had reached 10,000 a week. The total number of those who sought asylum in the country in 2015 was close to 163,000. The following year, that fell to just under 29,000.

The change of policy had its desired effect, but it left an edge of bitterness in Swedish politics, not least towards the rest of Europe. In the summer of 2014, the centre-right prime minister Fredrik Reinfeldt had given a memorable speech in which he called on Swedes to ‘open your hearts’ to those fleeing for their lives. Now, the thought came: if only other EU countries had been willing to open their hearts, Sweden would not have had to go against its own moral inclinations, its instinct to generosity.

As Kilian Kleinschmidt said, the million people who came to Europe in 2015 did this continent the service of revealing the gaps within our systems and our stories. What kind of poverty did their arrival disclose within our seemingly so affluent societies? On what basis might Europe become a continent capable of accommodating and living together with the displaced? What we know of climate change, the consequences that lie around and ahead of us, makes this no academic question. Might we need to start somewhere other than the high ideals enshrined in doctrines of human rights, themselves so tangled up with the high-minded stories we like to tell about our continent and its role in the world?

There’s a thread to pull on here that leads beyond where I am headed in this essay. For now, I remain impressed by the persistence of my Saturday fika friends and by the many small instances of hospitality I witnessed in the autumn of 2015 and the years since. It’s no small thing to live in a country that has as strong a tradition of welcoming the stranger as modern Sweden, and despite the dystopian exaggerations of the fear-mongers, the result has hardly been social collapse. Yet something else nags at me, an echo of Kleinschmidt’s words about keeping refugees as guinea pigs. Here’s what it is: with all its lingering self-image as a moral superpower, I don’t know whether this society realises how much it might have to learn from its newcomers, the extent to which they hold kinds of knowledge and experience that could make all the difference as times get harder, as I suspect they will, as the bubbles within which many of us have been living continue to burst.

* * *

We didn’t have to break up in order to get our post delivered to the new apartment. The system proved more amenable than Anna had feared, on this occasion, yet the fear was not entirely unreasonable.

There is a ‘Computer says no!’ quality to Swedish society, a sense that for anything to work at all, it must fit within the categories and fields of bureaucratic forms. What is striking to me, as an incomer, is how natural this seems to everyone else. It’s a testament to how well the system mostly works that it is not treated as a joke, in the way bureaucracies very often are. Instead, Sweden is exceptional for the level of trust that people have in institutions.

My friend who bought the plane ticket from Madrid describes the experience of being picked up by immigration officials at Stockholm’s Arlanda airport. Among the questions he was required to answer, they asked whether he was a Sunni or a Shia. It was, he says, the first time in his life that he had been made to define himself according to these categories, and he refused. ‘Well,’ his interviewer said, ‘I have to put something here. You’re Kurdish and Kurds are mostly Sunni, so that’s what I am putting.’

When you are born in Sweden, you are issued with a Person Number, a ten or twelve-digit code that starts with your date of birth. Introduced in 1947, this was the first such system anywhere in the world to cover an entire population. Having a Person Number is a necessity for interfacing with numerous systems, public and private, and all newcomers given residency are issued with one. When I got my last four digits, as the expression goes, I was surprised to discover it even worked for borrowing DVDs from the local video store.

All societies are full of their local mysteries, ways of doing things that are obvious to those brought up in them and baffling to the alien. But I wonder if any society has so deeply internalised the impersonal logic of the Person Number, the assumption that reality consists of things which can be indexed through categories and forms, existence as an entry in a database? When I listen to enthusiasts for the Blockchain talk about a near future in which entire legal codes have been uploaded and their inconsistencies ironed out, this vision of a world shorn of ambiguity, illegibility and the messy layer of human interpretation sounds to my ears like a strangely Swedish utopia.

It’s a logic that goes deep. Remember my caveat to the New York Times description of the folkhemmet: ‘the country is a family and its citizens take care of one another’, but only through the impersonal vehicle of the state. The collective project of social democracy, born out of grassroots movements of mutuality and solidarity, became in its institutional realisation the platform for a radically individualist society. Dependence on the flawed and fallible fabric of human relations was swapped for dependence on the impersonal mechanisms of the state, and in many ways this looked like a good deal. The result is a society that resembles the vision of Liquid Modernity described by Zygmunt Bauman, in which all human relationships have become disposable, to be dissolved at will, with little cost or consequence. It is an achievement which produces a kind of liberation I do not want to dismiss lightly, even as I cannot deny my unease at its wider consequences.

Anna remembers her return to Sweden as the loneliest time of her life. She had lived elsewhere for the best part of twelve years, most recently in Alexandria. There, if she kept to herself for 24 hours, her friends would come knocking at the door to see if she was unwell. In Stockholm, no one ever called by on the off-chance she was home. To make plans with old friends or new colleagues involved planning weeks ahead and coordinating around people’s slots in the shared laundry rooms that sit in the basements of Swedish apartment buildings. From a society only held together by the dense weave of human relationships, she had returned to one of order and independence and isolation, to a city with a median household size of one.

Is the Swede Human? asks the title of a much-debated book by the Swedish historian Lars Trägårdh and the journalist Henrik Berggren. Trägårdh’s ideas have found an international audience through Erik Gandini’s documentary, The Swedish Theory of Love, while an English synopsis of the book was distributed at Davos a few years ago. It is an enquiry into the peculiarity of Sweden’s ‘state individualism’, following its roots back beyond the beginnings of social democracy and into the cultural history that formed the Swedish character. It is not hard to get onboard with the basic premise: in terms of the argument I have been tracing here, the inclination to treat reality as made up of things that can be indexed and categorised seems to stretch from Linnaean taxonomy to the more didactic forms of normkritik. It’s also fair to note that Trägårdh’s arguments can be turned to serve the interests of those who historically opposed the creation of the Swedish model, in as much as they locate the credit for its achievements within the traits of a national character, rather than with the social movements which built modern Sweden.

If social democracy flourished in Sweden and came further in realising its vision of modernity here than anywhere else, it seems reasonable to look for the particular conditions that enabled it to flourish. The historical experiences, landscapes and cultural values which shaped this country may well have left it predisposed towards the social contract of state individualism, but the creation of the institutions and agreements by which that deal was made a reality propelled the inhabitants of the people’s home to a previously impossible level of independence from direct human relationships. In the ‘good family’ that grew out of Per Albin Hansson’s vision, not only were there no favourites and no stepchildren, there would be no need for actual family at all.

Loneliness is not an easy thing to measure. At best you can look for the statistical traces that it leaves like footprints in the sand. Last December, the newspaper Dagens Nyheter reported that every other day in Sweden, a body is found of someone who has lain dead, undiscovered, for a month or more. Other markers of a rising tide of loneliness might be found in the figures for mental illness among the young, or even in patterns of consumption so endemic we rarely acknowledge how closely they conform to the dynamics of addiction.

This is not the violent dystopia of the Sweden the US president learns about from Fox News. It is closer to the general trends observed across the western societies, though pushed towards the extremes in a society that can seem on the surface to be insulated from the ills of neoliberalism, and that serves too often as a vessel for nostalgic hopes, a place where the dream of a kinder modernity is rumoured to be still alive.

Of course, you might say loneliness is a price worth paying for all the gains Hans Rosling used to show us on his graphs, a luxury problem in a society that has met its more pressing needs. Except that the ecological realities of the 21st century bring back Orwell’s charge of hypocrisy in a new and deadly form: according to the WWF, the ecological footprint of the average Swede outstrips that of almost all other European countries. For everyone on Earth today to share this enlightened standard of life, we would need three more Earths.

In the newsagents at the railway station, I pick up a strange publication, a Franco-Swedish ‘bookazine’ called Good Future (‘Inspired by UN Sustainable Goals’). All the articles are in English, including a lead essay from Johan Norberg, Rosling’s successor in the optimism export trade. Alongside it, there’s a ten-page feature in which editor Annelie Karlsson drives a Tesla from Stockholm to Provence.

No one I know who actually works with climate change is persuaded by the path to the future on offer here, the green consumerism that has become so much a part of Sweden’s identity today. Perhaps it’s telling that Greta Thunberg – the most famous Swede in the world, right now – has received a rather muted response at home. Compared to the mass school strikes in Australia, Germany, Belgium and elsewhere, Swedish pupils have been slow to follow her example. Could it be that the cognitive dissonance between her message and everything the adult world is telling them is just too great?

‘We are coming down to earth,’ says the poet-philosopher Bayo Akomolafe, ‘we will not arrive intact.’ It occurs to me that the air of unreality surrounding much of the eager eco-optimism I encounter in Sweden is a reflection of how far this country has to fall. The Swedish model was built on industry, on the export of raw materials and high modernist design, on rising affluence and consumption. Its achievements do not insulate it against its unsustainability. There will be no smooth transition here, or anywhere else, but on the rocky road of the decades ahead, it will surely have to remember some of the skills of mutuality and interdependence that seemed obsolete when it occupied the high ground of modernity.

If that is so, then Sweden may yet come to be grateful for the knowledge of people who came here from countries further down the league tables of economic development and who carry the lived experience of how to make life work under less orderly conditions. It may find, too, that there are currents within its own past and present that contribute to this remembering – not least, at the edges, including the rural and ex-industrial communities that have been treated as a threat or as a joke. For the grand stories that get told about a country and its national character are always full of gaps, threaded through with other lines of history whose significance may reveal themselves in hindsight.

* * *

On a Friday lunchtime, three weeks after my bag was stolen, I walk through the sliding doors of the Swedbank branch in the city centre, take a queue ticket and find a seat in the waiting area. At one of the stand-up desks that line the far side of the room, I hear a member of staff explaining to a couple who want to open an account that they need to speak to a national call centre, this isn’t something they can do here in person.

Like most of us in the waiting room this lunchtime, I’m guessing, the couple are still wandering in to Sweden. There are exceptions: a man around sixty comes in, with a tan that says he’s spent the summer sailing in the archipelago, and is directed upstairs for a meeting with a financial advisor; there’s an elderly woman, accompanied by her daughter, but otherwise we all seem to be what they call New Swedes.

I remember a conversation one day in class: most of our group were convinced that the old Swedes, the white ones, had become a minority in our city. When we looked up the statistics and found that only one in four of our neighbours had an overseas background, this was met with disbelief. In the queues at banks, at council offices, at bus stops, we are over-represented. We are less likely to go everywhere by car, to do our shopping online or out of town. It takes eight years on average, they told us at the start of that course, for an immigrant with a professional education to reach the point where she gets employment appropriate to her skills: we were here so they could help us get there faster. How much of that eight years is spent waiting around, I wonder? In queues, in the corridors of language schools, on street corners.

In July, the city lays on a festival, with bands and stalls that line the downtown streets. Among the crowds, we run into Baha, a friend from the Saturday fika group. He laughs and shakes his head, gesturing around us. ‘Swedish people only know how to use the streets when someone tells them that they can!’

My number comes up on the digital display and I’m shown through to a side office; in my hands, the documents I collected this morning from the police station. Not only a new ID card, but a passport, a magical instrument that means I can walk in and out of other people’s countries as though this were nothing. I know it isn’t nothing.

Strange to see it there in black and white: Nationalitet: Svensk. I am Swedish people now. For bureaucratic purposes, at least, I stand solidly inside the walls of the people’s home, even if in other ways it still feels like I’m lingering in the doorway, eyeing the whole structure with suspicion. My papers are the proof that I have been adopted into the ‘good family’, with all its quirks and secrets. Like most families, it has stories that it loves to tell and stories no one wants to talk about. In another seven years, perhaps I’ll understand it better.

After the train had crossed the bridge and we’d left behind the Malmö skyline, it hit me with an unexpected force: this is my country now, with all that is easy to love about it and all the rest, too. Its troubles are my troubles. When I write about its tangled history, I cannot do so with detachment, because I have become part of the tangle. Perhaps this was why I needed the three months in England, so as to come back and see this clearly, to lose any remaining illusion of distance.

England will always be my past, my childhood home – and the past is never gone – but in as much as one can take such things for granted, I am here to stay. Running in my head are some half-remembered words, recited by Zlatan Ibrahimovic in a Volvo ad, the last lines of the Swedish national anthem, which don’t quite go: ‘I will live, I will die in the North.’

* * *

So what did happen in Sweden, when the far right won 17.5% of the vote in last year’s general election?

Three days beforehand, the New York Times had run an op-ed under the headline, ‘How the Far Right Conquered Sweden’. The author, a political editor at a German newspaper, told readers that the Sweden Democrats ‘might end up in government’, that their success ‘makes a coalition between the Social Democrats and the Moderates unlikely’, but that both of these large historic parties might well split as a result of the vote. As James Savage – co-founder of Sweden’s English-language news site, The Local – wrote with some exasperation, these were ‘things that no one who has observed Swedish politics could assert’:

The piece, like so many others, goes on to paint a dystopian picture of Sweden that is at odds with the experience of most people living here. A few anecdotes about gang violence in the suburbs leave the reader with the false impression of a society in decay…

Sometimes, disinformation is not the result of dastardly plots by the enemies of democracy, but simply the decline of the foreign correspondent. (When I worked for the BBC in South Yorkshire, we’d sometimes get calls from producers in London who would start, ‘Newcastle, that’s near you guys, yeah?’ I imagine the Times editors calling up Hamburg on a similar basis.)

When all the votes were counted, the red-green bloc – made up of the governing Social Democrats and Greens, with the arms-length support of the Left party – had 144 seats in parliament to 143 for what’s still known as the ‘bourgeois’ bloc, the four centre-right parties collaborating under the banner of the Alliance for Sweden. During the closing weeks of the campaign, there had been much discussion of scenarios, but few imagined the result would be quite so tight. The leader of the Moderates, the largest of the Alliance parties, Ulf Kristersson kept repeating the mantra that he would push their policies ‘right into the tiles’, a metaphor lifted from the world of competitive swimming that allowed him to hint that he would look for a way to govern with the support of the Sweden Democrats, if need be, without ever actually saying as much.

One of the quirks of the Swedish system is its reliance on ‘negative parliamentary confidence’: to form a government, a prime minister does not need to command a majority in parliament, only to ensure that there is not an absolute majority of parliamentarians willing to vote against him or her. This makes an abstention as good as a vote of support, so much of the emphasis in building a government can go into which parties are willing to ‘lay down’ their votes and tolerate a prime ministerial candidate.

When the new parliament met, its first act was to vote down the existing government of Stefan Löfven, the Alliance parties going together with the Sweden Democrats to create a majority against his red-green coalition. This set in motion a drawn-out process of meetings between the party leaders and the speaker of the house, with the mandate to lead negotiations on forming a government passing backwards and forwards. What became clear over the months that followed was that the strength of the far right had driven a wedge between the established bourgeois parties. Kristersson got as far as assembling the numbers to vote down the continuity budget of the caretaker government, still led by the ousted Löfven, and replace it with an Alliance budget. But on the question of forming a government – which, whatever sophistry might be deployed, would be mathematically dependent on the ongoing support of the Sweden Democrats – two of the four Alliance parties had to draw the line.

Pushed to choose between fresh elections, tolerating a Moderate-led government reliant on the far right, or tolerating the return to power of their Social Democrat opponents, the Liberals and the Centre party finally opted for the last of these, to the indignation of their allies in the Moderates and the Christian Democrats. The far right had not conquered Sweden, but it had succeeded in fracturing the alliance between conservatism and liberalism that had composed the country’s centre-right. In this respect, the wranglings over the formation of a Swedish government prefigured the deepening divisions within the Tory party as Boris Johnson pulls it closer to the national conservatism of the Faragists.

In the op-ed pages of the Swedish press, there was talk of the left-right axis giving way to the GAL/TAN scale: Green, Alternative and Libertarian voters on the one side, Traditionalists, Authoritarians and Nationalists on the other. The conditions under which the liberal parties agreed not to oppose the new government included tax cuts for the highest earners and other reforms that built on the agenda of the earlier Alliance governments, and at the last minute, the negotiations almost fell through, as the Left party threatened to vote against the formation of a new government on these terms. Meanwhile, commentators began to speculate about the emergence of a new conservative bloc. Recent polls show the combined support for this putative alliance the Moderates, Christian Democrats and Sweden Democrats averaging around 45%: strong, but not enough to take them to power.

As a weakened red-green coalition settles into its second term of office, Swedish politics remains in a precarious situation, its politicians unsure how to absorb the lessons of recent elections; in other words, it resembles the ordinary condition of most of the Western democracies today. There is a sense of a phony war, a not-quite-convincing simulation of normality, but along what lines would such a conflict be drawn? It is easy to imagine ourselves in a reenactment of the 1930s; the rhetoric is borrowed from that decade, often enough, and any complacency towards the ghosts of history should be gone by now. Yet this reading of the times may be too easy, a way of avoiding harder tasks for the political imagination.

Some clues as to what these tasks might look like can be found in Bruno Latour’s recent book, Down to Earth. Though far from complete, it contains sketches for a new political cartography that starts from the assumption that widening inequality, mass migration and the oncoming climate crisis are far more tightly interconnected than we have known how to talk about. The politics towards which Latour is gesturing is one that grasps the stakes of the 21st century and the challenge of finding common hopes on the far side of the failure of modernity. It finds in the figure of Donald Trump an embodiment of that which needs to be opposed, but it does not pretend that opposition can take refuge in the reanimated forms of older liberal or progressive politics. Its implications deserve an attention beyond the scope of this essay.

Meanwhile, in the absence of such a politics, one of the winners of Sweden’s phony war has been Annie Lööf, leader of the Centre party. Born out of the Farmer’s League that helped Per Albin Hansson form a government in the 1930s, Lööf’s party has mutated into a vehicle for social and economic liberalism. Their parliamentary votes and her leadership were decisive in holding the line against the Sweden Democrats, preventing the creation of a government over which the far right would exercise power, yet Lööf herself is a self-professed admirer of Margaret Thatcher and Ayn Rand.

I met someone who had lunch with her a few years ago and he told me an interesting story. He’d asked what she thought were the greatest challenges that lay ahead for Sweden in the coming generation. An ageing population, the automation of work and climate change, she answered. He pressed her on the last of these: did she really think that technology was going to get us off the hook, that we could continue on our current path of economic growth and ever more consumption? ‘I am an optimist,’ she declared, her smile firmly in place. A statement of faith. An end to the conversation.

* * *

Before we go, there’s just time for one last question, and this one comes from a caller in New York – the friend who sent me the article that set me writing. ‘How much of this is true,’ he wants to know, ‘according to you?’

Well, it’s true that there’s a lot of disinformation about Sweden, much of it painting a dystopian picture. Among the actors involved, there surely are dark forces from other corners of the world, though they are far from having a monopoly. As we have seen, the New York Times itself is quite capable of playing its part in the promotion of a distorted view of this country.

There is a party with neo-Nazi roots that has found that a defence of the political tradition of the folkhemmet has a broader appeal than the direct messages of racial hatred that it used to trade in. This party has established itself as the third largest parliamentary force in Swedish politics. For any of us to whom such politics is inimical, for any of us who bear the mark of otherness or care about those around us who do so, there can be no complacency here.

As with its associates in other countries, the growth of this party has been fed by an online ecosystem, a digital shadow media, parts of it homegrown, parts of it fuelled by global networks of social media designed by Silicon Valley to profit from antagonism and addiction. Within that ecosystem, as the Times has demonstrated, there are strange alliances and bad actors, some of them state-backed, seeking to stoke hatred and anger.

From the experiences of people I know, it’s clear that there is a poison at work in Swedish society that is far more toxic than the well-scrubbed, TV-friendly spokesmen of the Sweden Democrats want to admit. It shows itself when people think they are talking among friends, or through the safety of keys and screens and usernames. It spreads fear and despair among those who understand themselves to be its targets.

In the end, the least convincing part of the Times article is its headline: the claim that a global machine lies ‘behind’ the rise of the far right. As we’ve seen, this argument stumbles on the timeline. It’s not just that the 2018 election result fell short of the Sweden Democrats’ ambitions. As pointed out by Christian Christenson, a Stockholm-based American journalism professor, while the international media reported a ‘surge’ in its support ahead of the election, the party had in fact been flatlining in the opinion polls since 2015. This seems hard to square with the idea that ‘the workings of an international disinformation machine’ lay behind its success, unless we are to believe that the power of this machine had begun to wane, back before Trump had emerged as a contender, before the Vote Leave campaign had started to gear up.

Sinister as they may be, the connections which the New York Times is able to reveal are at most an exacerbating factor in what has been happening in Sweden. To place them at the centre of the story is to use them as a comfort blanket, a way of avoiding harder thoughts. This kind of comfort, we can ill afford.

Västerås, 30 August 2019

First published on Bella Caledonia, 13 September 2019.