The kaleidoscope has been shaken, the pieces are in flux, soon they will settle again. Before they do, let us reorder this world around us…

Tony Blair, 2 October 2001

I didn’t make it to bed on election night, so it took till Saturday morning to have the experience of waking up in this new reality. All day, I felt a lightness, like the laws of physics just changed slightly — and scrolling through Facebook, I see others trying to make sense of this strange sensation. Mixed in among these posts, though, there are others that boil down to, ‘Will you all stop smoking whatever it is you’re smoking?’

With that in mind — and with one or two sobering caveats — I want to explain why I’m convinced what happened last Thursday is among the two most important and hopeful events in British politics in my lifetime. And why that’s still true, even if you have no time for Corbyn’s politics or his party. (In which case, you can probably skip the next couple of paragraphs.)

First, the sobering bit. Labour lost — it just lost less badly than everyone expected. May is back in Downing Street, promising another five years of Tory rule, only this time propped up by the even-nastier party. There’s plenty been said already about why the role of the DUP is troubling — not least, its potential to jeopardise what must be the most important and hopeful development in British politics in most of our lifetimes, peace in Northern Ireland. Oh yes, and meanwhile, a prime minister who couldn’t manage a competent election campaign is about to embark on the multidimensional chess of the Brexit negotiations.

Now, you can come back against some of that: Labour’s vote grew by more than at any election since 1945, the party has momentum on its side, and neither May nor anyone else will be leading a Tory government for a full term. If it doesn’t fall sooner, a handful of lost by-elections will wipe out this government’s majority. (A thought sure to concentrate the minds of by-election voters — and Westminster averages about five by-elections a year.)

But I want to talk about something more important.

We’ve just had an election in which the full weight of The Sun and The Daily Mail was thrown at destroying Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour party — and, by any standards, failed to do so. This is so big that, among the rest of the post-election turmoil, I don’t think we’ve grasped what it means yet.

Since the 1980s, British politics has been locked in a basement by a gang of abusers, systematic perverters of democracy, chief among them Rupert Murdoch and Paul Dacre. 8 June, 2017 should be remembered as the day that we escaped.

That look you see on the face of Labour MPs who spent two years opposing Corbyn at every turn — it’s the baffled gaze of battery chickens who find the door to their cage left open. Their every reflex was formed by fear of a corrupted and corrupting media. Now, they are disoriented by the possibility of freedom.

I want to talk about why the current Labour leadership is strangely well-placed to take advantage of this new altered reality — and why seeing what just happened in these terms may be more helpful, when it comes to bridging divides, than assuming that resistance to Corbyn within the parliamentary party was all about ideological divisions.

So, there are going to be four parts to this story: the first is about the British media, the second about Labour, the third about the Tories, and the fourth about what kind of an event this is — and where things go next.

The Media

When Corbyn was elected leader of the Labour party, the British press went into overdrive. According to a study by LSE researchers, only 11% of articles about Corbyn represented his views without alteration; in 74% of articles, his views were either ‘highly distorted’ or not represented at all. The leader of the parliamentary opposition was systematically delegitimised ‘through lack of voice or misrepresentation’, ‘through scorn, ridicule and personal attacks’ and ‘through association’ with terrorists and dictators.

A newspaper can be as partisan as its editor and owner want it to be, but UK broadcasters are subject to a duty of impartiality. Yet the BBC seems to have been at best powerless to stop — and at worst complicit in — the capture of British democracy by a small ring of powerful abusers. It became so systematic, so embedded in the culture, that complaints weren’t taken seriously: when the BBC Trust upheld a complaint over a report in which Laura Kuenssberg made it look like Corbyn was answering a different question to the one he was asked, the director of BBC News dismissed the finding. Eighteen months later, in the final days of the election campaign, that misleading clip was still being shared widely with nothing to alert viewers to the upheld complaint. Overall, the role of broadcasters has been to recycle and amplify the newspaper attacks on Corbyn—something Barry Gardiner called out the Today programme over early in the election campaign.

The intensity of the press attacks on the current Labour leader may have been unprecedented, but it is part of a pattern of abuse that goes back — well, how far? I’ll be 40 this year, I’ve followed every UK election since 1987 (listening to Radio 4 on a transistor radio in the school playground), and I can’t remember a time when we had a normally-functioning democracy.

But the point where it became undeniable was the 1992 election and the famous front-page claim: ‘It’s The Sun Wot Won It’. Whether that was true hardly matters — for the next 25 years, British politics has been conducted on the assumption that it was. Until last Thursday.

The Breaking of Labour

Like a lot of the manoeuvres accompanying the birth of New Labour, Tony Blair’s courtship of Rupert Murdoch could be cast as a necessary evil. Yet there was always an excess to it; a suspicion that submission to Murdoch left him feeling excited, rather than sullied. The sense of betrayal which many Labour people feel when they think of Blair is usually explained in terms of Iraq, or of a preference for purity and principles over power; but when you think about what The Sun had done to Labour the last time around, the way Blair cultivated — and took pleasure in — his power-friendship with its owner was a fuck-you to the movement he was meant to be leading. And the impression of a weird edge to their relationship was bizarrely confirmed, after he’d left office, when he first became godfather to one of Murdoch’s daughters, then got accused by News Corp insiders of having an affair with Murdoch’s soon-to-be ex-wife.

Gordon Brown’s experience with the press was more straightforwardly miserable. He fretted about what Murdoch would say, but lacked Blair’s knack for flirting with Labour’s natural enemies, and his attempts came off clumsily. (Remember the time he invited Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street?) Thinking back on the tormented figure he cut, the stories of rages and sulks and thrown computer hardware, I’m wondering now — was this the behaviour of a decent man who thought politics was a serious business, but found himself trapped instead inside a game where every move had to be calculated for how it would play on the front of the next day’s Sun?

This brings us to Ed Miliband. Of all the politicians from New Labour’s ‘next generation’, he came closest to seeing the possibilities which Corbyn has now made a reality. Even his much-mocked meeting with Russell Brand in the closing days of the 2015 election campaign looks a lot less daft, given the wave of young and disenfranchised voters who showed up at the polls last week. But the instincts that drew Miliband in this direction were tripped up by a tendency to hesitation and to pessimism about politics.

Two quick stories that show this.

First, in December 2010, as the student movement started kicking off, Miliband apparently wanted to come down to the UCL occupation and talk with the students — an idea that divided his advisors, and that ultimately didn’t happen. Now, we can all guess what Corbyn would have done in his place, but the point is that Miliband’s instinct was to do the same thing — yet the supposed boundaries of what you can and can’t do in British politics, without getting destroyed, made him hesitate.

Another story… Ten years ago, I became an internet entrepreneur by accident. A small project snowballed into an educational web start-up, and by the summer of 2007, one of my co-founders was faced with a decision— was he willing to commit to the responsibility with which we were about to find ourselves? When we met, he’d been working at a think tank with close ties to New Labour — and one Sunday morning at a festival, he ran into an old friend who was now Miliband’s speechwriter. As they were talking about the choice he faced, Miliband himself strolled up and sat down beside them. Having listened for a while, he said, ‘You know, if I could start again, I’d be a social entrepreneur. That’s how you really change the world.’

And then came Jeremy Corbyn. What mattered about this Labour leader was not that he came from so far to the left, but from so far outside the game of ‘realistic’ politics which had led the likes of Miliband into that kind of pessimism about what politics could do. Meanwhile, the certainty of all the players within that game that he was headed for destruction meant he was spared the counsel of the kind of cautious advisors who fed Miliband’s hesitancy — because, for the past two years, those people just wouldn’t touch Corbyn with a bargepole.

The Spoiling of the Tories

The damage done to British politics by this decades-long cycle of abuse is obviously asymmetric—maybe I’m wrong, but I can’t see many areas in which the Tories’ desires have been constrained by the influence of Murdoch and Dacre. Yet, in their different ways, both parties have been deformed by that influence.

While the systematic abuse of democracy bred a broken generation of politicians in the Labour party, it gifted the Tories a spoiled generation:

- Some of them appear to truly believe the grim picture of the country they aspire to govern peddled by papers like the Daily Mail.

- Others were trained in the arts of distortion and fabrication through earlier careers as journalists and columnists — and assume these skills are adequate to the task of governing a country.

- None of them has had to engage in a real democratic tussle over the direction of the country, where their opponents don’t enter the ring already hamstrung.

That’s how a party once led by Winston Churchill ends up with a prime minister who resembles a malfunctioning robot — and a clownish con-man as its leader-in-waiting.

Again, this story goes back decades — but it came to a crunch in the past year. For just when, in Corbyn, Labour at last had a leader who didn’t fear the right-wing press, the Tories found themselves led by someone who aligned herself more tightly to them than her predecessors. Theresa May sought to govern Britain as an avatar of the Daily Mail. As Anthony Barnett wrote in October, this meant a shift away from the dominance of Murdoch — which had lasted from the Thatcher era, through the New Labour years, and survived the phone-hacking scandal (in which David Cameron’s director of communications, the former News of the World editor Andy Coulson, was sent to jail). More than this, as Will Davies points out, the economic irrationality of Brexit left May’s Conservatism more dependent on both Dacre and Murdoch: in contrast to Thatcherism, ‘it can’t rely on cheerleading from the CBI or the Financial Times.’

So the scene was set for the general election of 2017. It was not the threatened Brexit election — nor was it quite an election on the radical promises made by Corbyn’s Labour. (That’s what the next one will be about…) Rather, what we got was a Tory prime minister who had tied herself to the masthead of the Daily Mail versus a Labour leader with the guts to bet that the emperors would turn out to be naked. If the question was ‘Who governs Britain?’, the surge in support for Labour gave a resounding answer: not the Dacres and the Murdochs.

And yet, among the rest of the past week’s noise, not everyone has heard — with Michael Gove returning to the front bench, the chatter is of Murdoch’s influence over the Tories rising again. Well, long may that continue.

What kind of event was this election?

This feels like the angriest and the most hopeful thing I’ve written in years. Thinking about the role of Murdoch and Dacre and their co-conspirators, the hold they’ve had over democracy in the UK, I keep coming back to phrases that suggest sexual abuse — and maybe that’s distasteful, I don’t know, but the anger hits me like it did when the BBC finally had to face up to having filled our childhood afternoons with celebrity paedophiles. Maybe it’s because of how long it’s gone on, how many people have known and treated it as just how things are. And maybe I’ve no right to use such an analogy, because it’s not something that’s ever been done to me. Honestly, I don’t know.

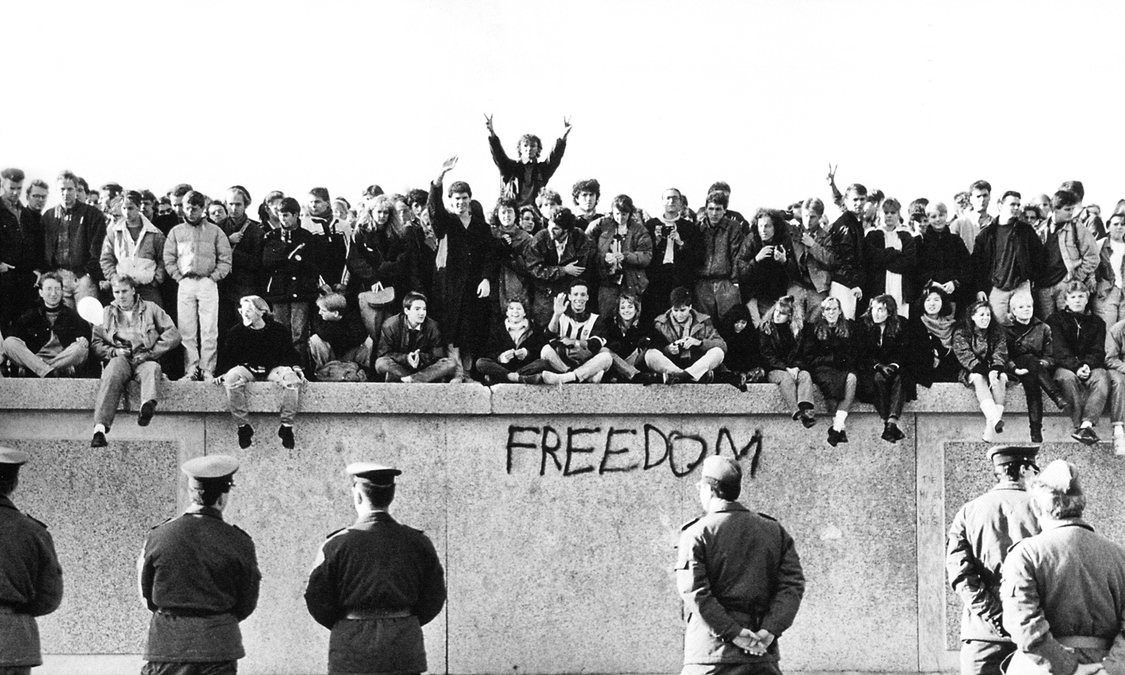

What I do know is that we have another frame of reference for what happens when a gang of unelected bullies takes political control over a country and turns its ‘democracy’ into a pantomime, staged within limits which they get to determine. When I was a kid, half of Europe fitted that description — and then, one autumn, young people called the bluff of the people who thought they ran their countries, and it all came down faster than anyone could believe.

I’m not saying what just happened is as big as the fall of the Berlin Wall, but the hope that’s mixed with the anger is because I think it might just be the same kind of event.

What do I mean? Well, firstly, that this isn’t a swing of the pendulum. Word is that Murdoch stormed out of The Times’ election party when the exit poll was announced — and well he might, because we are never going back to a world in which he gets to determine what the Labour party can or can’t do. And that means that Britain is a democracy again — not a perfect democracy, and with an electoral system that’s badly in need of reform, but a country where real democratic change feels possible.

The generational nature of what happened matters, too. Because it gives the lie to all the smug bullshit about young people not caring — and because those young people will be back, next time around — and because, just in terms of demographics, it means that the fear-fuelled, tabloid Toryism of this election campaign is on its way out.

A wall that ran down the middle of British society has been breached, and my guess is there are still more people pouring through it in the days since the election. That breach isn’t going to go away because the Tories find a less robotic front-person.

As for Labour, it’s a strange chance that not only does the party find itself with a fearless and vindicated leader, but, in Tom Watson, a deputy leader who took on the Murdoch empire with courage over phone-hacking — making him a strikingly appropriate figure to help the party orient itself to a world in which Murdoch and his like are no longer to be feared.

A final thought (or three)

A few years ago, I sat in the office of an editor in Prague, a man who had been among the crowds in Wenceslas Square in those late autumn weeks of 1989. He’d been a student, then, and we talked about the disillusionments that followed.

‘I’ve lived 21 years under communism,’ he said slowly, ‘and 21 years under capitalism — and I can tell you what’s wrong with both.’

Did he ever regret what they had done, I wondered?

‘I don’t regret what we did,’ he replied. ‘I regret what we let the grown-ups do, after we went home.’

The fall of the Murdoch wall may be a huge thing for British democracy, but its rise was part of something bigger that stretches far beyond the rainy islands where I did my growing up. One day soon, I need to write up a set of thoughts that have been gathering for a year or so, about how we map the politics of ‘neoliberal realism’ and the search for the exits — a story that takes in the Brexit vote and Corbyn’s rise, but also the shifting political landscape in other corners of Europe.

Meanwhile, beyond all this, there is the low background roar of loss, the knowledge that we are living in an age of endings. I’m writing this late at night, after the first day of a meeting on ‘rapid decarbonisation’ — and the message from the scientists here is beyond sobering. At times, it’s hard to hold in view the different scales of crisis: the unravelling of an economic ideology that’s less than a lifetime old, playing out against the backdrop of the end of a 10,000 year mild period in the Earth’s climate which happens to have encompassed all that we’ve known as civilisation, and an ongoing mass extinction, the sixth the planet has seen in its long life. All these endings are entangled with each other. We have brought about an almighty bottleneck, and it’s hard to say in what shape our kind will come through it, except that the journey will change us in ways beyond the imaginings of the things I’ve been writing about here.

But if I stare at these realities and still, despite the woeful absence of such matters from the debate in this election, see some hope in the unexpected wave that just washed through Britain’s political system, it’s because it will take waves like this — sudden ruptures that spread like rumours through the spaces of conversation and networks of relations that make up our lives — if things are to turn out better than often seems likely in the tight times that lie ahead.

I was going to wrap this up by saying something like, ‘Don’t go home and let the grown-ups fuck it up.’ But then I read Dan Hancox’s piece this morning on the extraordinary surge of grassroots campaigning that produced last week’s results, and I’m like — go home? As if you would. As if any of us are about to do that, now.

Published on Medium in the wake of the 2017 UK general election.