‘I want to tell you a story about Boris Johnson’s heart. There’s a woman involved, but this isn’t what you’re thinking.’

Tag: politics

What’s Happening in Sweden?

A long read about Sweden, its story of itself and the role this country plays in the political imagination of millions of people who have never been here.

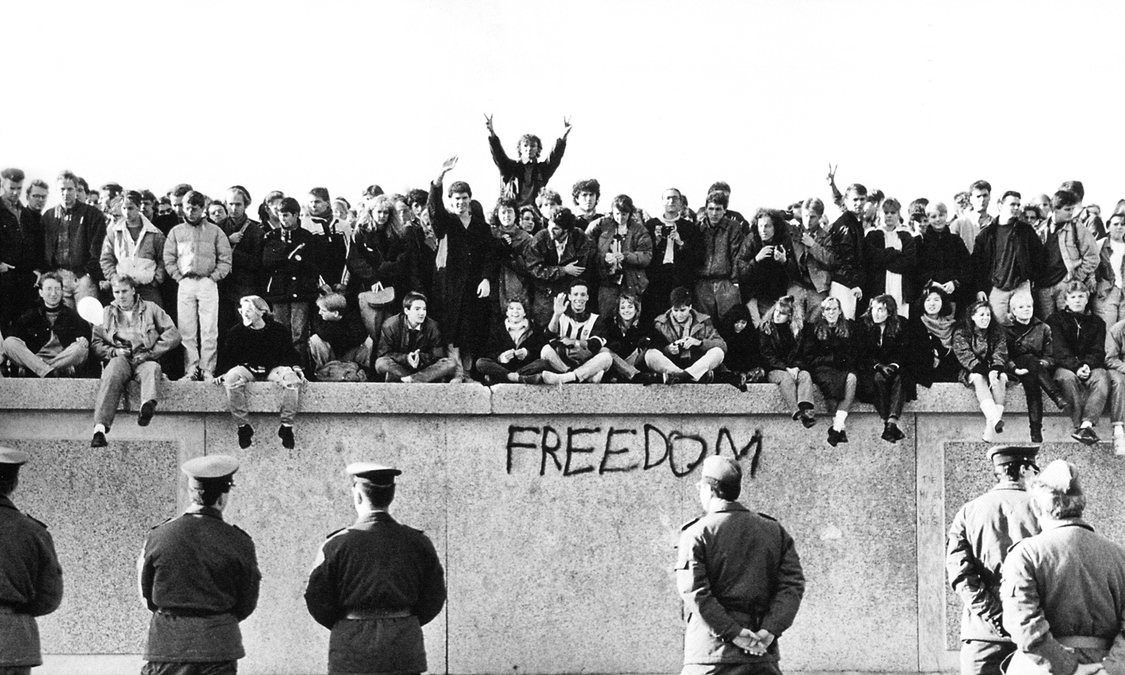

The Fall of the Murdoch Wall

Reflections in the aftermath of the UK general election of 2017.

An angry, hopeful reflection written in the days after the UK general election of 2017.

You Want It Darker

When the regular mechanisms of political narration break down, there is a need for something stranger: liminal writing for liminal times.

When the Maps Run Out

A letter I sent to readers of Crossed Lines, three days after the election of Donald Trump

A piece of political science fiction, imagining what it would take for Jeremy Corbyn to make a success of his leadership.

Few things I’ve written have been more widely read than this blogpost from the morning after the UK general election of 2015.

Let’s Get This Party Started!

A short story written for 28 Days, a one-off newspaper published during the UK general election campaign of 2015.

Who Cares About Democracy?

Speaking at TEDx Uppsala in 2014 together with Lisa Färnström.