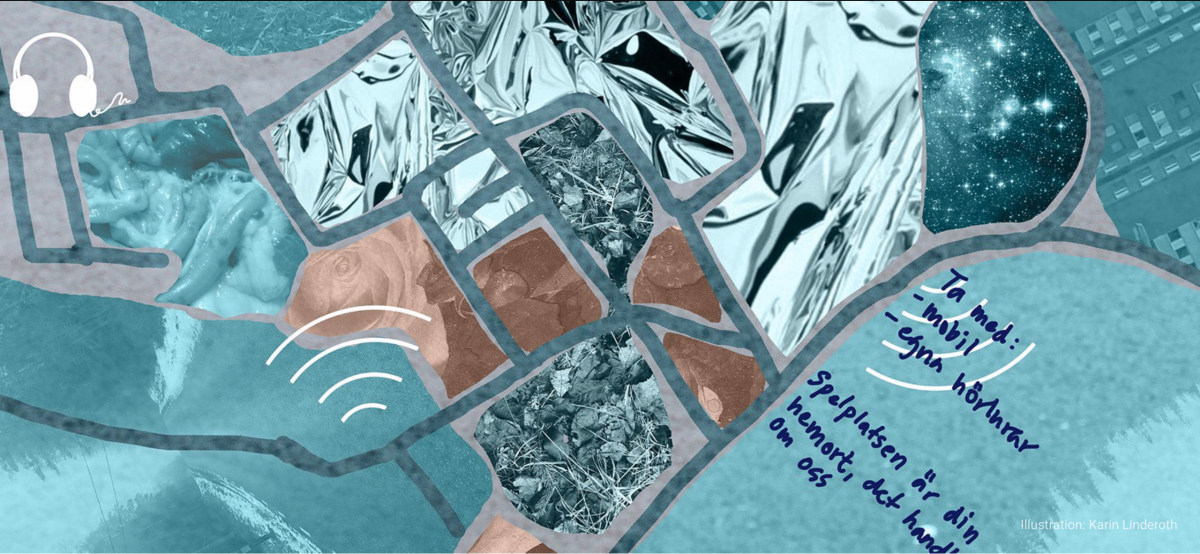

This month sees the premiere of an audiowalk production that’s the final piece of the repertoire programme I helped to create during my time at Riksteatern. As part of the production, I wrote and recorded a reflection on the future.

Tag: theatre

An unfinished list of the roles that art can sometimes play. This comes from the work I did with Riksteatern in 2015-16.

The Consequences of Unacknowledged Loss

An essay written for the programme for the Orange Tree Theatre production of Joe White’s Mayfly.

Medan klockan tickar at The Stockholm Act

A fresh outing this week for our play about what it’s like when the Anthropocene is your day job.

You Want It Darker

When the regular mechanisms of political narration break down, there is a need for something stranger: liminal writing for liminal times.

A play commissioned by the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm about what it’s like when the Anthropocene is your day job. Co-written with Anders Duus, Nina Tersmann & Jesper Weithz.

I’ve co-written a play for the Royal Dramatic Theatre, Stockholm about what it’s like when the Anthropocene is your day-job.

Maps for the Journey

A report from a session with the artist Monique Besten, midway through the Dark Mountain Workshop project at Riksteatern.

The Dark Mountain Workshop (2015-16)

What does art do when the world is on fire? In the autumn of 2015, I brought together a group of fourteen artists from within and beyond the performing arts.…

In the fifth issue of Crossed Lines, I introduced my new role as leader of artistic and audience development at Riksteatern, Sweden’s touring national theatre.