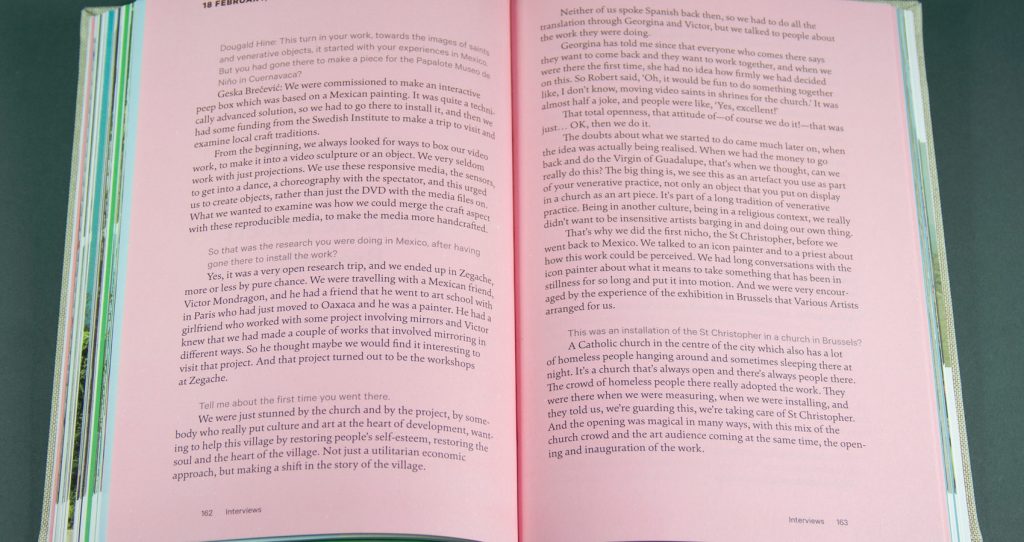

I still remember the night we were first brought together for dinner by a mutual friend and we laughed so much all night we said, we have to do this again tomorrow, and we did. That’s how we got tangled up with each other.

It’s a strange experience to go to a friend’s PhD defence and hear them present words that I wrote. Together, Ana Džokić and Marc Neelen form the architecture practice STEALTH.unlimited. Since we met in 2012, our friendship has been an ongoing collaboration – and so it was an honour to be asked to contribute to the collaborative doctoral thesis which they have now successfully defended at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm.

It was an opportunity for celebration – and also to glimpse the territory we want to go further into together. It was also a chance to meet Katherine Gibson, who took on the role of ‘opponent’ in a rather gentler fashion than the term would suggest, and whose work on rethinking economies has long been a source of inspiration to me.

Here’s the main section that I contributed to the thesis.

From the Dead Centre of the Present

It seems that we were following similar hunches, for years, before we were introduced. The crisis of 2008 had set us on these tracks – or rather, it meant that the tracks we were following anyway seemed suddenly relevant to people who hadn’t noticed them before, so that we found ourselves needing to reformulate, to express what it was we thought we had caught sight of.

In my case, this took the form of Uncivilisation: The Dark Mountain Manifesto, written with Paul Kingsnorth and published in 2009. The hunch that we tried to put into words was that the crisis went deeper than almost anyone wanted to admit, that it went culture deep, that it was a crisis of the stories by which our culture has been living. And if this is true, we thought, then might it not follow that the work of telling stories and making culture becomes central to the task we face, the task of living through dark times and finding possibilities among the ruins.

The tumbling weeks of crisis turn into months, years, and a new normal establishes itself, but it is never the promised return to normal. Eight years on, Dark Mountain has become a gathering point for people trying to work out what still makes sense, in the face of all we know about the depth of the mess the world is in.

A mountain is not exactly an urban thing, though! Sometimes I tell people, it’s not a place you live the whole time: it’s a place you go to look back and get a longer perspective, maybe even to receive some kind of revelation, but you still have an everyday life to return to, back in the city or the village. That’s what I enjoy about this friendship and collaboration with STEALTH – and joy is a word that should be mentioned here, you know! I still remember the night we were first brought together for dinner by a mutual friend and we laughed so much all night we said, we have to do this again tomorrow, and we did. That’s how we got tangled up with each other.

Now, tracing our tangled trajectories across these past eight years – you bouncing between cities, me wandering up and down a mountain of words – I see two stories that we seem to have in common. The first is spatial, the second temporal.

The spatial story concerns a negotiation between the edges and the centre. I need to be careful how I say this, because we have all been told about the way that whatever is edgy, new, avant-garde gets metabolised, made palatable, made marketable and becomes the next iteration of the centre. That’s the story of selling out, or buying in: the great morality tale of counterculture.

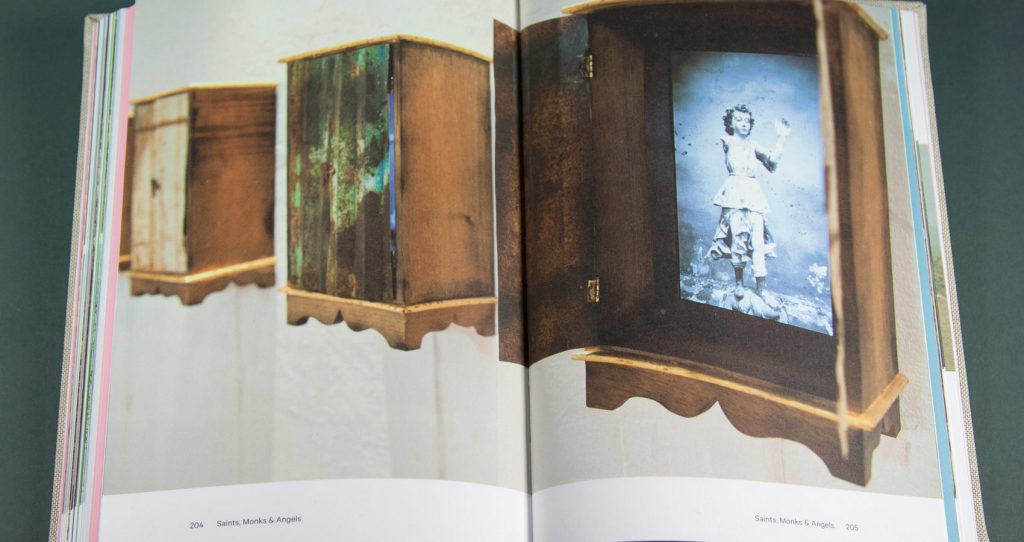

The story I’m trying to tell, here – the one I say we have in common – starts with the claim that the centre as we know it is already ruined beyond saving. This is what I see in that image of the burnt-out architecture faculty in Delft in ARCHIPHOENIX. In the manifesto that Paul and I wrote, we speak about this: “None of us knows where to look, but all of us know not to look down. Secretly, we all think we are doomed: even the politicians think this; even the environmentalists…” And then we ask, “What would happen if we looked down?” What if we admit that the centre is already a burnt-out ruin? Might we need to ask ourselves what it is, exactly, that is doomed: what version of ourselves, what set of things (structures, institutions, customs) with which we have identified?

If this is the kind of mess we’re in, then the challenge for those of us at the edges is neither to retain our countercultural purity, nor to negotiate good terms on which to cash in with a centre that is already collapsing – nor even to try to shore that centre up and prevent its collapse (too late!) – but to offer something that could take its place.

“Sometimes you have to go to the edges to get some perspective on the turmoil at the heart of the things,” writes Paul Kingsnorth, my co-founder in Dark Mountain, in late 2016. “Doing so is not an abnegation of public responsibility: it is a form of it. In the old stories, people from the edges of things brought ideas and understandings from the forest back in the kingdom which the kingdom could not generate by itself.”

The arrival at the centre of a figure from the edges is the opening move in many an old story. But the negotiation cannot set anything in motion, so long as the pretence is maintained that business can go on as usual, that a return to normal is on the cards.

So when STEALTH asks how those practices which already showcase possible directions could be “made to work… on a scale that answers the challenges ahead?”, what is in question is not ‘scaling up’ for the sake of profitability, but what might take the place where the centre used to be. How do we find ways of going on making things work when – as in The Report – the all-powerful operating system breaks down. Like Anna Tsing, we are looking for the possibilities of life within capitalist ruins.

“The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop,” we write, on the last page of the manifesto. The ruins are not the end of the story. Ecologically, the species present (our species included) go on improvising ways of living together, even with all the damage. There are things to be done: salvage work, grief work, the work of remembering and picking up the dropped threads.

This is where we slip from the spatial to the temporal. What is at stake in the temporal story is how we find leverage on the dead centre of the present. Not so long ago, the future served as a point of leverage: a place from which to open up a gap between how things happen to be just now and how they might be. That gap was charged with possibility.

Here I think of the work of Tor Lindstrand, to whom you introduced me in that project in Tensta, ‘Haunted by the Shadows of the Future’. He tells the story of the disappearance of the future in urban planning: the evaporation of any vision or belief in the possibility that things could be different, as the development of cities is subsumed into the operation of the market and marketed with bland identikit images and words. The role of financialisation in this reminds me of William Davies’ description of the consequences of monetary policy under

neoliberalism:

The problem with viewing the future as territory to be plundered is that eventually we all have to live there. And if, once there, finding it already plundered, we do the same thing again, we enter a vicious circle. We decline to treat the future as a time when things might be different, with yet to be imagined technologies, institutions and opportunities. The control freaks in finance aren’t content to sit and wait for the future to arrive on its own terms, but intend to profit from it and parcel it out, well before the rest of us have got there.

If the future is already plundered – and if, as Dark Mountain points out, the consequences of related kinds of plundering for the ecological fabric stand in the way of any revival of the confident future of modernity – how else can we open up that gap in which the possibility of change, the non-inevitability of present conditions, can be located?

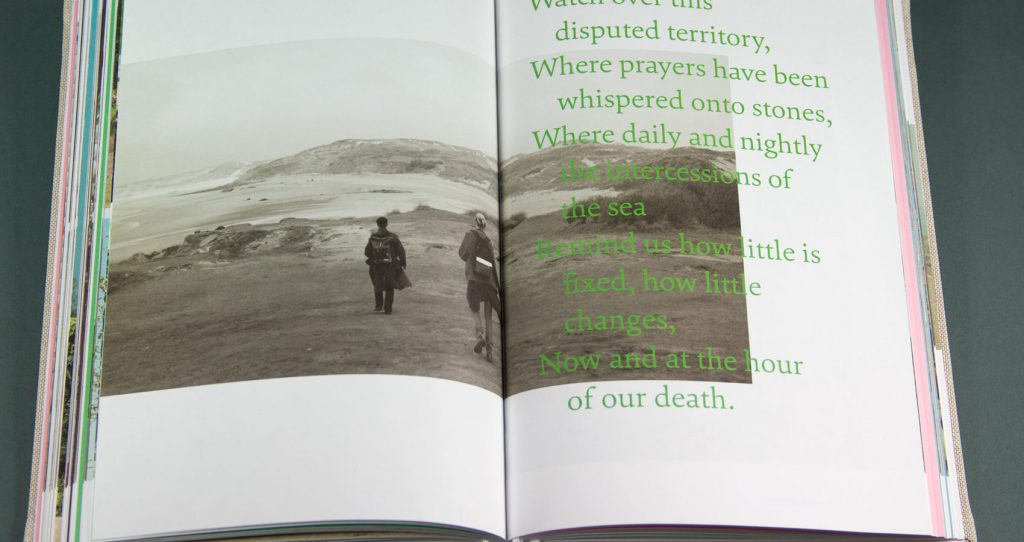

The great improvisation teacher Keith Johnstone says that, when telling a story, you shouldn’t worry about what’s coming next: you should be like a person walking backwards, looking out for the chance to weave back in one of the threads from earlier in the story. We move through time backwards, like Walter Benjamin’s ‘angel of history’: we cannot go back and fix the mistakes of the past, but at least it is there for us to see, in a way that was never true of the future. Ivan Illich writes of ‘the mirror of the past’: if we look carefully into it, without falling into romanticism and without dismissing it as simply a poorer version of the present, then the past too can serve as a source for a sense of possibility. In a time of endings, one of the forms of possibility it offers is the dropped threads of earlier endings – the way of life which is now falling into ruin was built among the ruins of earlier ways of life.

I see this as central to the method by which you seek to build possible futures, in Bordeaux and Vienna, in Rotterdam and Belgrade, and elsewhere. I remember sitting in a seminar room in Gothenburg as you showed us images of that mutual aid society in the Netherlands in the 1860s, created by workers to build their own homes. A trajectory can be traced from this initiative to the grander state projects for welfare of the mid-20th century, to the hollowing out of those projects under the neoliberal period of marketisation, to the crisis of 2008 in which they are revealed as ruins. Even as you go about improvising practical strategies to bring these ruins to life, you are always looking back to the beginnings of the story and asking what has been lost or written out, in the way that it has been told.

In THE REPORT, you reveal the pattern by which the role of bottom-up initiatives in the building of the city have been written out of Vienna’s story. What emerges from these researches and the future narratives which they inform is the realisation that, in many parts of Europe, the achievements of social democracy were born out of movements which looked far more like anarcho-syndicalism than those who later consolidated these achievements into top-down state systems would be willing to admit.

Those movements were born out of necessity, operating within the ruins of the commons, devastated by the early phases of industrial capitalism; now, after 40 years of neoliberalism, as we look for ways to operate within the ruins of the welfare societies of the 20th century, their histories can help us open the gap between how things are and how they might be.

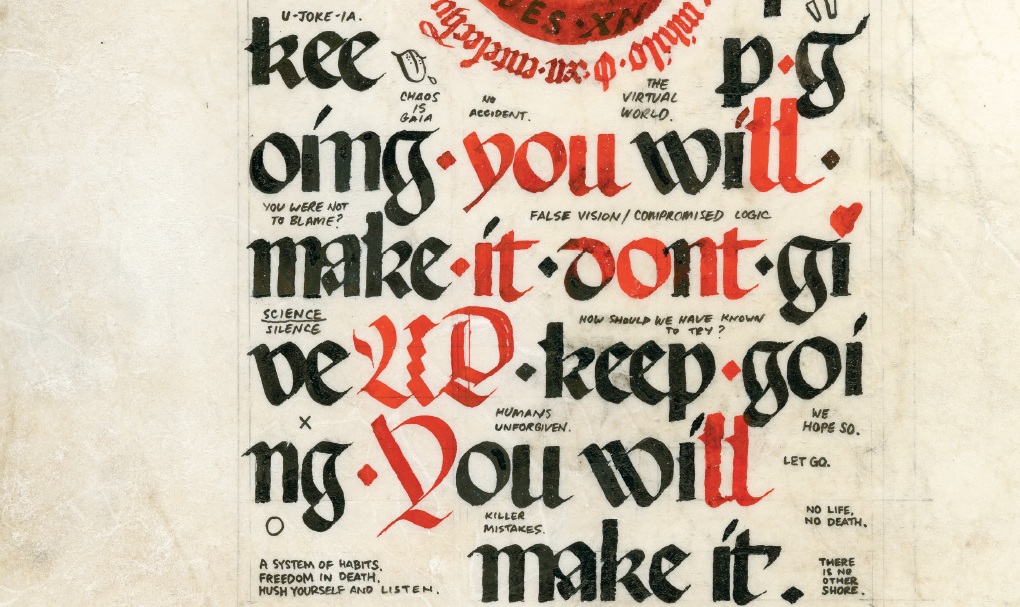

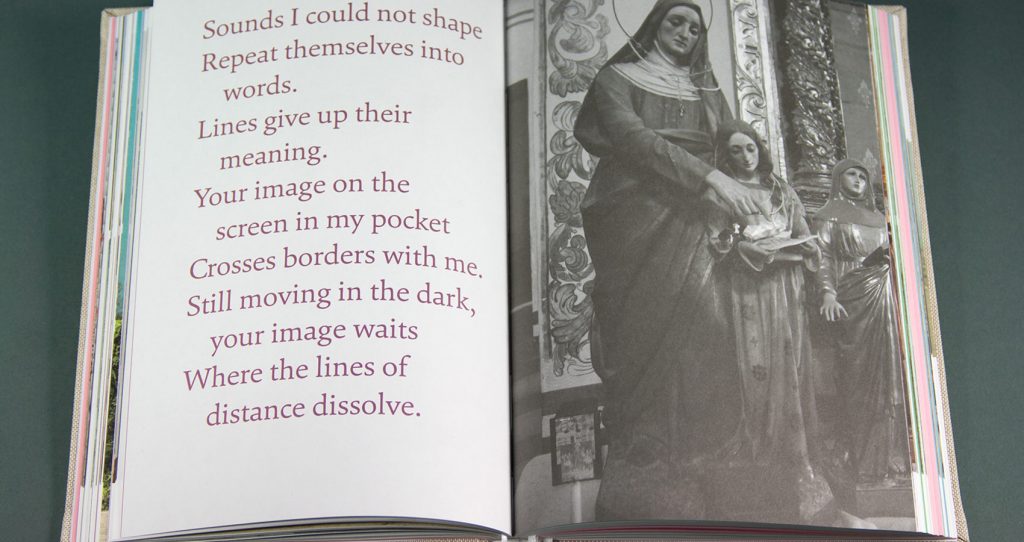

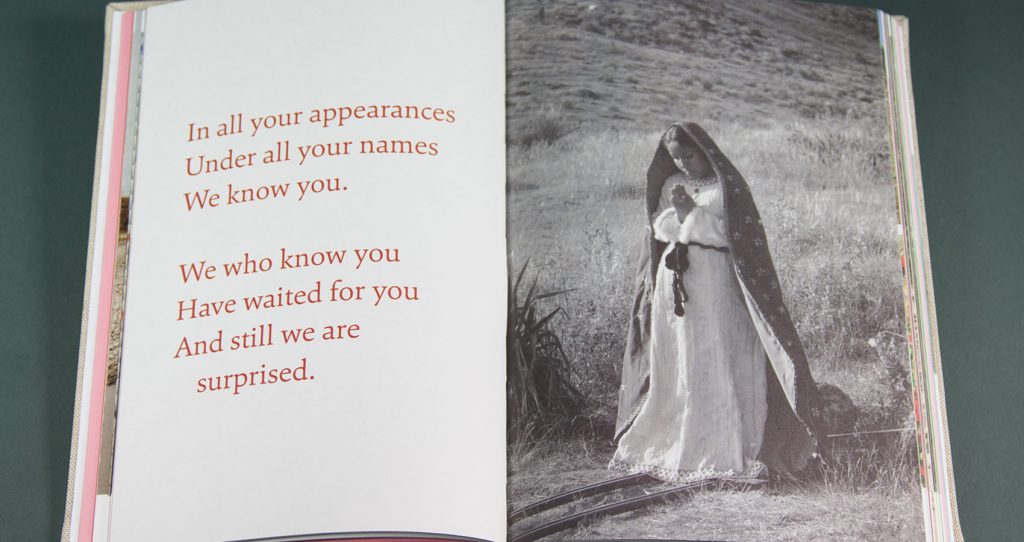

We meet in the conviction that telling stories is not just a way of passing the time, but the way that we find our bearings in the world. A story opens a space of possibility into which we can invite others and when the work of building new projects among the ruins is at its hardest, when we wonder if it is worth going on, it is by retelling the stories that we connect ourselves to the past and the future, place ourselves within time. The right story, told from the heart, can be the difference between going on and giving up.