for Charlotte Du Cann & Mark Watson

In dreams begins responsibility.

W. B. Yeats

Now, I will simply do these maintenance everyday things, and flush them up to consciousness, exhibit them, as Art.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles

The books live under the stairs. There are boxes of back issues stacked in a Narnia wardrobe. Twice a year, a truck pulls up in the lane outside the cottage and offloads the latest issue, stacked on wooden pallets. If they are lucky, the truck driver stops to help Charlotte and Mark get the boxes indoors, where they will be repacked and sent out to over a thousand subscribers.

This work could be outsourced. There are distributors who take on publications like Dark Mountain and they probably charge less per copy than the handling fee the pair of them get paid, but the money would no longer go towards paying the rent on this old cottage which serves not only as depot but as editorial headquarters and the home of the people who carry the day-to-day responsibility for the whole operation as it heads into its second decade.

I visit in early June and it’s still chilly enough to light a fire in the wood stove in the living room. (Those pallets don’t go to waste.) It’s a rare chance to work together face-to-face, rather than the hundreds of hours we’ve spent on Skype, as I hand over the last of my responsibilities for the publication I co-founded a decade ago.

We walk from Reydon into the small town of Southwold, a seaside place where London people come at weekends. Charlotte takes me to see the mural of Orwell under the pier. We stop in at the Sailor’s Reading Room where Sebald stops off in The Rings of Saturn and I realise that it’s time I read that book again. At the beachfront café, we find a sheltered table to eat our ice creams. Soon we’re joined by Heidi, the new bookkeeper, who lives in a flat above the market square.

On the way back, we call in at the Post Office, where all those books get posted. The postmaster comes out to shake my hand. ‘Thank you,’ he says with feeling. ‘You don’t have to put your business through us and it makes a huge difference.’ In recent years, Dark Mountain has grown to be his biggest customer, sending thousands of packages a year. There must be cheaper and more efficient ways to do this, but to change it now would be unthinkable. Standing here, I feel what it means that our small publishing operation has become a part of the economic ecosystem of this corner of Suffolk. It’s one of the reasons why Southwold still has a Post Office, when many English places of its size do not.

I wish I could say that we set out to create a publishing operation which embodied a Polanyian idea of the social embedding of economic activity, but the truth is things ended up this way more by accident than design.

Like the stapled together news-sheets I made as a child, or the photocopied zines of my late teens, Dark Mountain was the product of the pleasure of making a platform together with the necessity of doing so in order to write the things I wanted to write. Something similar applied to my co-founder, Paul Kingsnorth, whose idea it was in the first place, and our collaboration was born of a hunch that we weren’t the only ones in need of this platform.

The first few hundred copies of our manifesto lived under my bed in Brixton. Orders got sent out when I remembered, or when readers emailed to ask why theirs still hadn’t come. The way that leads from dreams to responsibility was a shaky one. Even the crowdfunding of the manifesto was a close thing: a few months later, the site we had used went bust, taking with it the funds of any outstanding campaigns.

The playwright Mark Ravenhill gave a lecture a few years ago at the opening of the Edinburgh fringe festival. He started with a story from the Facebook feed of a younger theatremaker, describing a dream in which he is at dinner with a man who plans to kill his wife. No one else knows about his plan. The man is also the owner of a fleet of rental vans. If the dreamer keeps quiet, he’ll give him a cheap deal on a van to get his show to Edinburgh. He wakes before the choice is made, but is troubled to realise he was tempted.

To get our artistic dreams on the road, Ravenhill goes on to argue, we have to make a cut between two sides of ourselves, to be like Jekyll and Hyde, or the heroine of a play by Bertolt Brecht. On the one side:

to be a good artist you have to be the person who walks in to a space and tells the truth. That’s what marks you out from the audience and why they’re sitting over there and you’re standing up there: you are the most truthful person in that room.

On the other side, how do you get there? ‘Chances are by being a liar, a vagabond and a thief.’ You have to be cunning and ruthless enough to make your own luck.

I don’t want to play the innocent, to pretend I don’t recognise what Ravenhill is getting at, and I’ve quoted his speech with enthusiasm elsewhere. That line about the duty to be ‘the most truthful person in that room’ catches at something important. Yet as I reflect on a decade as writer, editor and publisher at Dark Mountain, it makes me want to unsettle the neatness of the binary he sets up, because it is in danger of affirming an idea with which I cannot hold: the separation between the high, true work of art and the low, grubby business that supports it, a necessary evil and a source of contamination from which the art itself must be protected.

For a start, it should be obvious that art deals in a tricky kind of truth. It’s hardly as though we leave our cunning at the stage door. To make theatre is to traffick in illusions: I think of Simon McBurney inThe Encounter, alone on stage, whispering into a cast of microphones, turning the audience’s headphones – the ultimate technology of isolation – into a device of hair-raising intimacy. To be an artist is to be a trickster, and that holds for poets, performers, playwrights and painters alike. Picasso had a point, old monster that he was, when he said, ‘Art is the lie that tells the truth.’ Having tried it on for size in the early years of Dark Mountain, I’d caution against the mantle of the artist as lonely truthteller. Self-proclaimed honesty is a dodgy business, as the signs over used car salesrooms attest. Do what you have to do and let others be the judge of how close to the truth you came.

Meanwhile, the clean cut between the truth-work of art and the wheeler-dealing that underpins it sits uneasily with me, too. I want to call instead on the Maintenance Art of Mierle Laderman Ukeles, refusing to respect the cordon sanitaire between high and low status work, making the shit-work visible, maybe even playful, honoured instead of taken for granted. I’d call too on the cunning and grace of an artist like Theaster Gates, and on Kate Rich’s Feral Trade, where the art is another way of doing business. I don’t say we got close to the way these artists work in the practice of publishing Dark Mountain, only that the times when the work felt truest for me were the times when I caught a glimpse of those possibilities.

‘Poets are a special case,’ I wrote in Issue 1 of Dark Mountain. ‘Yeats is allowed to be silly, because poetry is not required to make sense.’ It’s a theme to which I’ve returned more than once: the artist as a special kind of grown-up, the only grown-up allowed to go out in public without wearing the clothes of economic rationality. The other side of this strange coin is that the everyday economic reality of life for the average artist in many modern societies has involved a degree of precarity that was, until recently, beyond the experience of most of their fellow citizens. One consequence is that many of the artists and writers I have worked with show signs of post-traumatic stress in their relationship to money.

This colours the tensions that exist between the artistic vision of a project and its economic viability. Among the initiators of artistic projects, the work of book-writing might be seen as a higher calling than the work of bookkeeping, but it seems that society at large does not agree, since bankers make fortunes and accountants rarely worry about how to pay the bills, while award-winning authors often struggle to make ends meet. In the background of all this is a pervasive though rarely disclosed assumption: that pay should come as a reward for doing things you didn’t want to do. The very self-directedness of artistic work, the sense that we do things we love, contributes to the vulnerability of the artist as economic actor. The experience of being out of place in the economic game, of knowing the work you do doesn’t make sense according to the logic that dominates the society you live in, can breed an aversion to thinking about the economic aspects of that work. So you insist that a spreadsheet is beyond your comprehension, because innumeracy has become a matter of identity, a sign and a symptom of being on the side of the poets.

The time would come when I made my peace with spreadsheets, but early on I was as prone to this as anyone. It was a humbling moment when it finally hit me how much of the hassle we went through with Dark Mountain might have been avoided if we had set the price of our first issue five pounds higher, but I don’t remember putting any serious thought into that decision at the time. We didn’t model its implications, we just plucked a number from the air.

In the first two years, we ran the project unfunded, fitting the work in around other paying gigs, raising money through crowdfunding to cover the upfront costs of publication, paying ourselves a bit when there was money spare. By year three, this approach was under strain, as the workload grew. With the help of Michael Hughes, a friend and supporter, a funding proposal was put together. This was immediately successful, securing a grant of £10,000 per year for the next three years from the Deep Ecology Foundation, along with a one-off donation of £5,000 from a radical philanthropist in the UK.

Together with the profits from book sales, this allowed us to set up a modest part-time salary for a team of two: Paul was paid for ten days a month as director, with Sophie McKeand as his assistant for one day a week. By this point, I was burning out and moving countries, but I remained sufficiently involved to share responsibility for the decisions that followed.

There’s a pattern I’ve seen a few times now where money comes into a project previously held together by love and bits of string, and instead of this steadying the ship and allowing those involved to do what they’re already doing without making fools of themselves, it inspires a flurry of further activities. There was a touch of that over the next two years: when the last copies of Issue 1 sold out, we decided to splash out on reprinting it; we put time and energy into an album of music made by friends of the project, and the crowdfunding campaign for this was the first in which we missed our target. The premise of our funding proposal had been to bridge the way to self-sufficiency, to a point where sales of books would cover the work of running the operation, but there was no process in place to get us from here to there. Meanwhile, a decent desire to cheer each other on and avoid shame or blame could lead to a reluctance to name our mistakes and see them clearly.

Towards the end of year four, we hit a crisis: our small non-profit company was weeks away from running out of funds. For me, this was the moment when responsibility arrived. Having let others carry the weight of the project up to this point, I now became its existential backstop, the catcher in the rye who would do what it took to keep this thing from running off a cliff. That meant dropping other commitments, teaching myself new skills and taking on tasks I would hardly have chosen, because there was no one else around to do them and they needed to be done.

So I ditched the crowdfunding model that had funded the first three books, because it meant much of our energy went into banging the drum to bring in money from the same 200 readers every time we wanted to go into print. To launch the rolling subscriptions system that replaced it, I had to plan out a business model that meant we could be confident of fulfilling our readers’ subscriptions, and then build the section of the website where they would subscribe. This worked – and when it proved that seven out of ten subscriptions rolled over smoothly from one year to the next, we finally had a path towards the self-sufficiency we had promised our funders. In the meantime, though, we had to cut back what we spent on paying ourselves to half of the already frugal budget. Rather than take a slice of this for myself, I dropped the creative and editorial side of my involvement to allow time for other jobs that could help pay the rent. Though the truth is, the biggest funder of Dark Mountain in the years that followed was my partner Anna, who brought in the regular income that allowed me to put in so many hours unpaid.

The next turning point came as we hit year eight. Book sales and subscriptions had steadily grown, and with them the everyday work of running the operation. On paper, we were covering our costs, and we had begun to raise the fees we paid to editors, but in reality much of the work going into the books was underpaid. Two things exacerbated this: a drift in the relationship between work and money, and a lack of communication. When Paul and Sophie started getting paid, the principle was simple, with each of them paid the same amount per day. But as roles changed and were handed on, the memory of this was getting lost, and there was no process for checking how the principle was working out in practice and making changes. In fact, outside of the editorial process for a particular book, there were no regular meetings between those of us involved in running Dark Mountain, apart from an annual gathering that was usually tagged on to the excitements and exhaustions of a public event. Into this gap came all the ordinary human misunderstandings, the stories we tell about who is acting how and why.

There was a moment when it could have ended badly, but instead out of this drama came a recognition that we were no longer the ad hoc, books-under-the-bed operation of our beginnings. These days, we had a well-organised Narnia wardrobe! And we needed to organise ourselves in other ways. So I undertook to create just enough process to give some rhythm to our work, without draining the life from it. The old structure of directors assisted by staff – which sounds so formal, but had come about by default – gave way to a publishing collective, made up of the half dozen of us involved in the month-to-month running of the project, joined by a couple of members of the wider pool of editors. I instituted a monthly call for this collective and this was met with some resistance: when work already expands beyond the hours that any of us are paid for, spending another two hours together on Skype can feel like the last thing that’s needed. Yet the difference it made to our work together soon dissolved any scepticism. Most months, the first half hour would be spent just checking in, telling each other what we could see outside the window or talking about the books we had been reading. With a small team spread over three countries, some anchor point of shared presence is needed, however artificial it felt at first.

The other thing that came out of the year eight crunch was a written policy for how we ought to handle work and money. It started by acknowledging the gap between what we could pay ourselves, those of us doing this because it was Dark Mountain, and what we paid outsiders whose skills we needed. Handling our accounts, keeping the website up or printing the actual books: by now, we’d learned the hard way that having these services handled by friends of friends could be a formula for chaos, so we needed to be ready to pay the going rate. When it came to paying ourselves, the starting point was different: if all the work going into the books was paid at the rate it deserved, there wouldn’t be any books, but recognising this, we had to work towards a sustainable relationship between work and money, not just as an ethical commitment, but as a practical necessity. If those on whom the publishing of Dark Mountain depended were paid at a rate that meant they couldn’t make ends meet, it didn’t matter how much they cared about the project, sooner or later they would have to walk away.

With this spelt out, I proposed an ordering of priorities: first came the work that goes on week in, week out, handling orders, replying to emails, editing the website, because if the work you do for the project is part of your bread and butter, it has to be paid properly. Then came the project work, the editors who take on a time-limited task as part of the team coming together to work on an issue. This is intensive, hands-on work during the core weeks of the editorial process, but within the shape of your working year, it is feasible to balance it with other work that pays more and means less, so in the process of improving how everyone gets paid, this came second to the ongoing maintenance work. Finally, the hardest part, the payment of contributors to the books: hard because all of us on the publishing collective were also freelance writers or artists, and putting this work to the back of the queue felt like reproducing a pattern we had been on the wrong end of ourselves. From early on, we had commissioned covers for our books and paid the cover artists, but the work inside came from an open call. To pay the 50 or 60 people whose words and images appeared in a typical issue was an ambition we’d long held and one that still seemed out of reach.

It took until year ten, but we got there. After raising the pay for the core team and the book editors, after experimenting with small commissioning budgets, with Issue 15 – the last before I left – we were finally able to offer a fee to everyone whose work appeared in the pages of a Dark Mountain book. How best to do this was a challenge in itself: should we try to differentiate between a full-length essay, a twelve-line poem and a piece of flash fiction, or between a photograph documenting an existing art project and a drawing made for this book? What to do about the different situations and expectations of our contributors? In the end, my answer was to be as open with them as possible. We set aside a contributors pot, £1,200 in the first instance, and wrote to everyone whose work appeared in the book, explaining the situation:

From conversations with contributors over time, we know that there are those who are trying to make a living from their creative work (or simply to make ends meet), as well as others who are in full-time positions or have other means of support and would therefore be happy to go on contributing without a fee.

Contributors were invited to opt in or out, based on which of these best described their situation, with the pot split equally between everyone who opted in. (‘And if you have any hesitation,’ the instructions continued, ‘then we would encourage you to choose Yes.’)

In the event, the contributors to that book split half and half between Yes and No. Those who chose to receive a fee were paid just under £60 each. Not a great amount, but a start.

How strange to write so many words about Dark Mountain and hardly touch on its subject matter, the questions it asks, the claims it makes, the hunches explored within its pages! That story has been told already many times, by me and others: there’s half a shelf’s worth of books, the original manifesto, hundreds of press articles and interviews, and even the odd PhD thesis.

This other story I’ve been telling is only one of the lines that could be traced through this web of practice, the dream-led dance of how we became accidental publishers and learned to take responsibility. Name some of those other lines: Charlotte creating the role of producer, corralling editors and setting the tempo and holding the relationship between words, images and design; Mark holding the subscriptions system together and making it work; Ava Osbiston devising a submissions process for a publication that is not exactly a literary journal, that looks for raw potential as well as accomplishment, for the stories our editors can help to tell as well as the ones that arrive fully formed; Nick Hunt taking the website from a simple blog to an online edition that matches the richness of the books; Paul, from the very start, finding that our writing had created expectations and carrying responsibility for its consequences. Then there’s the physical work of printing, taking place beyond the horizon of our publishing team, under the direction of Christian Brett of Bracketpress, the one person to have worked on every single Dark Mountain publication. Each of them could tell another story.

Within this web of tasks and responsibilities, there is work that is unavoidably monotonous. Where this exists, the aim should be that it is done as humanly as possible, rather than as efficiently as possible; that those doing it are in charge of how it is done, that they know and feel why it matters, that their work is not forgotten or belittled, and that they have the chance to combine this work with involvement in other parts of the creative life of the project. The responsibility for making sure this is the case is shared by everyone involved in making decisions about the running of Dark Mountain.

Yet it would be a mistake to group together all the maintenance work and background process on which the artistic vision of a project depends and file it under that heading. My experience has been that it is possible to bring a degree of thought and care to these responsibilities that is in alignment with the more obviously artistic aspects of the work I got to do with Dark Mountain. There is an attitude here that can translate into many of the tasks that make up the practice of publishing.

To take one example: when the need arises to write to readers and supporters, asking them for money, this can be approached as something you hate but have to do. At that point, I’ve seen gifted writers descend into grating cliché, turning out a bad impression of a sales spiel, because they are approaching the task as an evil that cannot be avoided. The alternative is to find a way of writing that message in words that ring clear and true, that embody what you are doing and why it matters. There have been days when I think I found that tone.

Without making any stronger claim than that for the work I’ve done, I do believe there is a way of working that has truth in it. It isn’t easy, but nor is it complicated. At its heart, this way is about attention, which is why it has a lot to do with art. Attend to experience and let it show you what is missing from the stories you are telling. Attend to the relationships on which the work depends. Attend to what matters and whether it still matters. Attend to the alignment between what we say matters and how we treat each other. Look out for the moment when it’s time to stop.

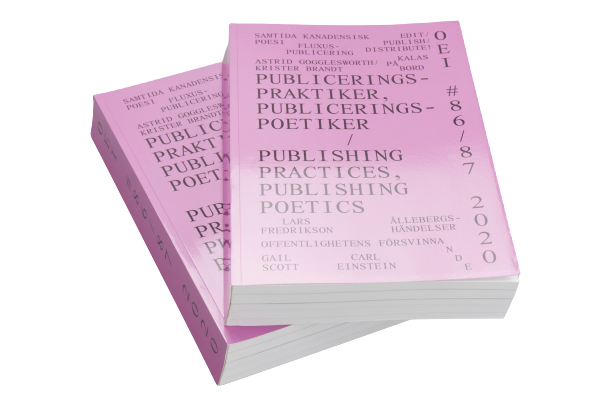

First published in OEI Issue 86-87, Publishing Practices, Publishing Poetics.