A problem calls for a solution; the only question is whether one can be found and made to work, and once this is done, the problem is solved. A predicament, by contrast, has no solution. Faced with a predicament, people come up with responses. Those responses may succeed, they may fail, or they may fall somewhere in between, but none of them ‘solves’ the predicament, in the sense that none of them makes it go away.

— John Michael Greer

The world is on fire.

We know this. We have been hearing the messages since we were in our teens. And somewhere down the line, it got real to us.

We changed lightbulbs like it would save the planet, clambered on desks at the end of late-night shifts to switch off every screen in the newsroom. We recycled with an obsessive compulsion. We got fired up by speakers at rallies, gathered signatures on petitions, marched chanting to the gates of summits.

And still a day came when doubt would not be ignored. We had to admit to ourselves that no amount of lightbulbs would be enough and we no longer believed that one more giant mobilisation of activists would do it.

What then? It’s not like we went out and bought SUVs. Many of the things we had done, we went on doing. It’s just that the slogans on the placards and on the adverts for the eco products no longer rang true; the movements we had been part of no longer spoke for us in the way that they had seemed to.

*

As artists, we found ourselves getting asked to help. Mostly this meant helping to deliver the message that the world is on fire.

It doesn’t work. The words slacken on the page; a gap opens between stage and audience. Art is not a communications tool for delivering messages and the importance of the message doesn’t change this.

Yet we cannot retreat into a feigned ignorance. To make work that pretends not to know that the world is on fire is to have a lie in our work like a worm in an apple.

So we begin again. We try to find ways to make work that can go into the darkness, go down deeper even than the mess we are in; work that crosses the rivers north of the future and comes alive, beyond all expectation, there, on the far side of hope.

*

Here is one measure of the depth of the mess we are in.

Since we were in our teens, scientists have been warning about the threat a changing climate poses to our whole way of life. World leaders have been making speeches about the need to cut emissions.

Eighteen years ago, they signed a treaty in Kyoto. In those eighteen years, there has only been one year in which global emissions fell. That was 2009, when financial crisis shrank the world economy. In 2010, emissions leapt by the largest amount ever recorded.

Not long ago, I listened to someone who has been in the negotiating rooms explain, quite calmly, that it would not be possible today to get the countries involved to sign again the agreements they already signed in the 1990s.

This is one measure of the depth of the mess we are in.

*

Listen to the words, though; the ones we use to talk about this mess. Don’t they die as they are spoken? Don’t they turn to ashes in the mouth? At the bottom of all this, there is something that turns our imagination to stone.

In old stories, there are forces like that, creatures so terrible that even to look on them would turn a person to stone. But there are also cunning ways to approach such creatures. Athena gives Perseus a bronze shield and, by following its reflections, he is able to creep up on Medusa.

There are stories that work like that shield, stories that give us a dark mirror with which to approach the source of our terror.

This could be the kind of clue we are looking for.

*

‘I haven’t a clue whether we humans will live for another 100 years or another 10,000 years,’ says our first guest, the storyteller Martin Shaw. ‘We can’t be sure. What matters to me is that we have fallen out of a very ancient love affair, a kind of dream-tangle, with the Earth itself.’

Could you get any further from the grown-up language in which serious discussions of our predicament are meant to take place? And yet, there is something here that demands admittance, a voice that will be heard.

Before all this is over, we will have to find a way to talk together again about loss and longing and love, and it will take voices such as this to call the deep words out of the private places within us.

This is the kind of task that lies ahead.

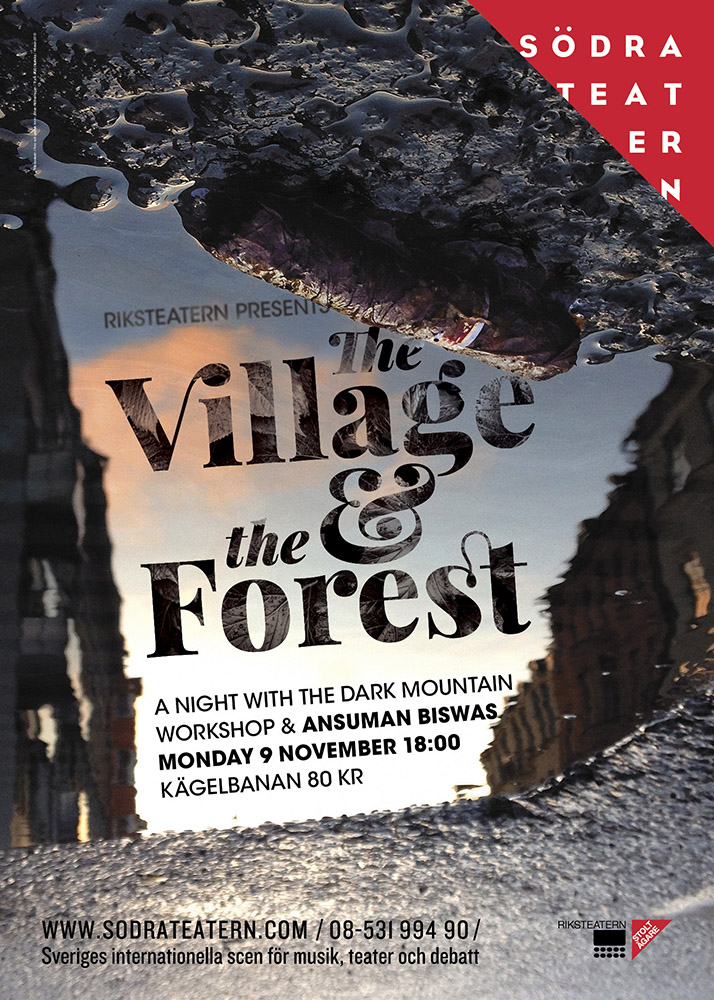

First published on the blog of the Dark Mountain Workshop, a project I created during my time as leader of artistic development at Riksteatern, Sweden’s touring national theatre.