I’m no philosopher, but I sometimes drink wine with philosophers, and by the time you get onto the third or fourth bottle, the conversation often comes around to the uncomfortable case of Martin Heidegger.

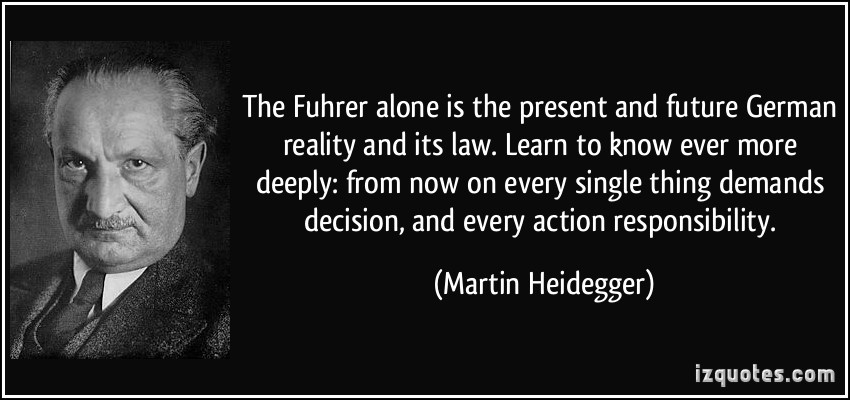

For my fellow non-philosophers, I think I can sum this up by saying: there’s this guy who is widely (not universally) considered to be one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century, but unfortunately he was also a Nazi — a Nazi who lived until 1976, but never got round to apologising for his enthusiasm for Hitler.

(You can just imagine how much ink has been spilt over this, but as a starting point, here’s the relevant section of his Wikipedia entry — while this from Joshua Rothman at the New Yorker gives you a flavour of the angst that philosophers go through.)

I find Heidegger’s style almost as unbearable as his politics, and probably for that reason he has had little influence on my thinking. But I’ve worked with people like David Abram and Tom Smith who have no sympathies with the politics, but find intellectual nourishment in other parts of his thinking. So I’m willing to accept that there may be things there worth drawing on.

(For what it’s worth, I suspect I found my equivalent nourishment in the work of Ivan Illich, who also offers deep critiques of technology and modernity, and for whom the concept of ‘home’ was also important — but who gets to this via pre-modern traditions of philosophy and theology, rather than leaning on Heidegger. That would be Illich who, aged thirteen, was called out in front of the classroom in Vienna and made to stand in profile, as the teacher pointed to his nose and told his classmates, ‘This is how you spot a Jew.’ Just saying.)

Anyhow, as an editor at Dark Mountain — where technology, modernity and the concept of ‘home’ are among the themes taken up by our contributors — I’ve struggled periodically with texts that are written for a general audience and draw on Heidegger without acknowledging his politics.

Basically, here’s how I see it: if you introduce Heidegger to a general reader with enthusiasm and don’t mention his unapologetic Nazism, sooner or later that reader will find out and feel betrayed. At which point, they will question your judgement — and possibly your political motives.

What got me writing about this today is a new essay from Charles Leadbeater at Aeon which is a great example of how to do this right. The whole essay is worth reading, but here’s the bit that’s relevant:

The philosopher who understood this search best is controversial: Martin Heidegger. A member of the Nazi Party, Heidegger never expressed remorse for the Holocaust and was often an arrogant, duplicitous bully. Some critics argue that his philosophy is too contaminated by racism to admit rescue. His ideas are often dismissed as parochial, nostalgic and regressive. Even his advocates acknowledge that his prose is deliberately dense.

Yet, as the Australian scholar Jeff Malpas has shown in several thoughtful books and essays, studying Heidegger helps to explain why we are now so preoccupied by feelings of displacement that are triggering a search for home. Given Heidegger’s Nazi leanings and the rise of the populist Right in many parts of the developed world, his work could repay study.

From here, Leadbeater is able to go further into what he — and Malpas — get out of Heidegger’s thinking, but the reader has not been set up for a horrible discovery at a later date. The thing that everyone needs to know when they engage with Heidegger has been stated clearly upfront.

I realise that, if Heidegger’s work matters to you, you’re probably sick of having to make the argument that his politics doesn’t render the rest of it off-limits.

When you’re writing in an academic context, it’s fine to assume that everyone knows the background — though please don’t make this mistake when teaching. (As Chenoe Hart pointed out in a discussion about this on Twitter this morning, you can go through architecture school hearing loads of discussion about Heidegger and never learn about the Nazism bit.)

And OK, I’m not actually saying you should always refer to him as ‘the Nazi philosopher Martin Heidegger’, but given that it’s not unusual — for example, in this great piece by Neil Fitzgerald — to read about ‘the Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek’, you might consider doing it now and then.

First published on Medium.