The setting could so easily seduce you. Painted wooden houses line three sides of a square of grass: the red house, the white house and the low wooden barn between them where the bunk rooms are. On the fourth side, the slope falls away, past the village library, past the station house and the railway tracks to the lake. A strip of an island a hundred yards offshore, then miles of water stretching to a wooded horizon.

The first clue that something is wrong should be the colour of the grass: dead-yellow already in the first days of June. No rain for weeks. The radio says we had the hottest May in over 250 years, but seeing as the oldest continuous temperature records anywhere began in Stockholm in the 1750s, you can probably stick a few zeros on that figure.

Now look again at the island – the one in the photograph on the homepage for this school called HOME – and see how it changes when I tell you that the scatter of low buildings by the jetty is the oldest preserved oil refinery in the world, the soil still poisoned from spills before our grandparents were born. This is where we meet, in a landscape whose beauty is haunted by a history of extraction. Whatever else there may be to say, this is the background against which our voices rise and fall.

A train pulls into the platform. Among the passengers who disembark, there are a number wearing rucksacks, looking around to find their bearings. They take in the lake and the island and the hostel on the hill. Together, they begin the short climb that leads to where we are standing, and, with their arrival, something shifts: this school, which has so far been a story Anna and I are telling, becomes something larger, messier and more substantial. For the next few days, in these borrowed buildings, it will be a place where our ideas and fears and longings get tangled up with those of the people who have taken up our invitation, an invitation to ‘a gathering place and a learning community for those who are drawn to the work of re-growing a living culture.’

* * *

One member of the group that week stands out in my memory. Fran is not the loudest presence; a large, gentle man in his early forties, he can be humble almost to a fault, yet there is a steadiness that marks him out. Here’s what I think it is: out of the whole group, he is the only one who hasn’t come alone. I mean, he made the journey solo, sleeping on overnight coaches, but he was able to do this thanks to the support of dozens of people who chipped in to crowdfund his way to Sweden – and so he arrives with a small village at his back, a community to which he already had to explain what was calling him here, and by which he is held. Sometimes in the sessions, I can see their faces leaning in over his shoulder.

A few months later, I’m planning a trip to England when I get a message from Fran: would I like to come and visit his hometown and give a talk? So that’s how the two of us end up sitting on this low stage in an arts space in Stroud, along with our hosts, Emily and Ali; the four of us watching as the seats fill up and the queue stretches out the door, hoping we don’t end up having to turn people away. Looking out at this crowd, I’m guessing a good few of Fran’s villagers are in the house tonight.

Well, it seems the folks without seats are happy to stand at the bar, and the whole room listens intently over the next two hours as we talk about what it might mean to take seriously the question with which the invitation to our school began: ‘What if the culture you grew up in was broken in ways that you didn’t even have words for?’ I talk about things I’ve learned over the past decade with Dark Mountain: about how despair is not a thing to be avoided at all costs, nor an end state; about how much of what makes human existence endurable lies beyond the reach of the state and the market, unmarked on the maps we’ve inherited from recent generations; about the role that art has played as a refuge for those aspects of reality that retreat from the gaze of those who would measure and price everything, that slip away like deer into the forest; about the hunch that, whatever hope is worth having today, it lies on the far side of despair, where the maps run out, at the margins or hidden in plain sight.

Fran and I talk about what it means to make room for this within the ordinary fabric of our lives, among the everyday pressures; creating pockets, spaces to which it is safe to bring more of ourselves than it would be wise to bring to many of the workplaces, educational institutions or families we have known.

Then right at the end of the night, just as Emily and Ali are drawing things to a close, they invite a friend up to the stage, a woman I haven’t met yet.

‘A few of us are organising a rebellion,’ she says. Not words I was expecting to hear, but as she goes on, I realise that I’m listening to something new – or new to me, at least. This is the voice of an activism that comes from the far side of despair, that has room for grief, that calls for courage rather than hope, that frames the stakes of climate change as starkly as anything we’ve published in Dark Mountain: this is not about saving the planet by changing your lightbulbs, it’s not about how we can sustain the way of living of the Western middle classes or fulfil the promises of development or transition to eco-socialism; it’s about how many species will be driven out of existence in the decades ahead, and whether our own is to be among them.

Two weeks later, Extinction Rebellion delivers its demands to parliament, and as November goes on, their actions bring parts of London to a halt: blocking the five main bridges across the Thames, then holding up rush hour traffic at key junctions around the city, morning after morning. Even the organisers seem taken aback at the scale of the response. The other week, my mum called to say she’d heard a BBC radio documentary about Gail Bradbrook, and wasn’t that the woman I’d told her about from Stroud?

From the occasional Facebook messages we exchange, I get the sense that Gail and those around her are riding a storm now, so I’m glad we got that chance to meet briefly in the relative calm of the weeks beforehand. And it seems fitting that the thread of serendipity which brought us together should run back to the gentle presence of Fran and the weave of generosity that brought him to Sweden in the endless days of early June.

* * *

‘What do you do, after you stop pretending?’

I wrote those words one night in the spring of 2010, as we were preparing for the first Dark Mountain festival. They became the frame for the Saturday programme on the main stage, and when Paul and I wrote a comment piece for the Guardian ahead of the event, it ran under the headline: ‘The environmental movement needs to stop pretending’. Among the crowd who gathered in Llangollen that weekend, there were those who came expecting us to offer a vision of what the environmental movement should do instead, and they were disappointed. I remember one guy from Manchester who was outright furious, railing to anyone who would listen, writing to us afterwards to demand that we refund his ticket.

Maybe there are people whose ideas are born crystal clear and arrive in the world just as envisaged in the imagination, but my experience has always been that projects stumble into being: any new undertaking has to wrestle its way clumsily through the muddle of what you thought it would be, past the temptations of what others want it to be, until – if you’re lucky – it starts to reveal what it’s capable of being. In the case of Dark Mountain, it was only some years in that I saw clearly that this project wasn’t the place from which to ‘do’ anything. Whatever else, it has been a place where people come when they no longer know what to do; a place where you can bring your despair and put it into words, without being judged, without feeling alone, and without a rush to action or to answers.

There’s a subtlety here that’s not well served by the pugnacious rhetoric of some of what got written in the early days. Activist writing often has the tone of telling everyone else what to do, and that certainly carried over into the ways I used to word things. The subtlety is this: to insist that the space you are holding is not one from which plans can be made or action taken is not to claim that no one should be taking action or making plans.

There’s a video on YouTube, an hour and eight minutes in the quiet, slightly shambly company of Roger Hallam. It was filmed in a university lecture theatre last May, soon after the meeting at which Roger, Gail and a few others came up with the idea for Extinction Rebellion. If you sit down to watch it, make sure you have time to get to the end: I had to stop halfway and wait till the next morning, and this was a mistake.

The first 40 minutes are where he presents the climate science, attempting to add up how much warming is already inevitable and where this would take us. There is something mesmerising about the parade of numbers – 1.2° that has happened already; 0.5° within a decade from the loss of the Arctic sea ice; another 0.5° from CO2 already emitted but not yet fed through into warming; the water vapour effect, doubling the impact of warming from other sources to give another 1° – and this is just the start, he adds. Somewhere around the 3° mark, we’ll lose the Amazon – assuming Bolsonaro hasn’t got there first – and this will bring another 1.5° of warming. Having got this far, Earth will tip further into a hot state, outside the conditions under which humans are capable of living.

I’ve been reading, thinking, writing and speaking about this stuff for long enough to know that a certain caution is called for. As one climate scientist put it to me, the bits we know for sure are scary enough, without stating worst-case scenarios as facts. Still, watching the first half of Roger’s talk was enough to give me a sleepless night. Maybe we need those nights every so often, to be brought back to the existential core of our situation, to have the layers of reasoning with which we insulate ourselves peeled off.

‘Why we are heading for extinction,’ begins the title of the talk, ‘and what to do about it.’ The remaining half hour is the bit about doing. What is striking is that Roger makes no attempt to row back on the bleakness of what he has already told us. There is no bargain on offer here – ‘If everyone does X, then all this scary stuff will go away’ – only the observation, backed up by research on social movements, that those whose willingness to act endures the longest are not the activists who are motivated by outcome, who need to be given hope and to believe in their chances of success, but the ones who are motivated by doing the right thing. It’s the first time I can remember seeing a call to action which explicitly invites people to go into despair. In the closing minutes of his talk, Roger speaks about ‘the dark night of the soul’, the need to move through the darkness rather than avoid it. This is a call to rebellion that is framed in the language and draws on the traditions of mysticism.

I don’t say that this is without precedent; indeed, part of Roger’s argument is that the rational, secular logic of mainstream Western activism, with its dependence on promises of progress, is the anomaly, while the stance for which he speaks has more in common with what has sustained grassroots movements in other times and places, and continues to do so. But this is the first activism around climate change in the West that I’ve encountered that has roots this deep, that draws on spiritual traditions without slipping into New Age wishful thinking or fantasies about a collective evolution of consciousness. It’s the closest I’ve seen to an activism that can answer that question I didn’t know how to answer back in 2010: what do we do, after we stop pretending?

* * *

In late July, we hired a car and drove north. This was the middle of the wildfire season, the Swedish authorities were dropping bombs on burning forests and borrowing firefighting planes from Italy. Our county got off lightly, but there were nights when you could smell the smoke on the air. We’d be following a backroad between villages and a convoy of fire engines would come speeding past. Coming home one evening, on the radio, two young hipster comedians from Södermalm were sniggering about how stupid the countryside people are and why don’t they just move to Stockholm rather than live out in the sticks and wait for their houses to burn down – and I thought: what the fuck, does it not occur to them that the rest of the country might be listening?

We stayed on a farm and the farmer told us that she had a problem: in this heat, the lambs didn’t notice the shock from the electric fencing, so they were getting out and running everywhere. But her farm was lucky, she said, they had about three-quarters of the fodder they would normally have at this point in the year. In other parts of the country, farmers were trying to send their animals to slaughter because they couldn’t feed them, except the slaughterhouses couldn’t handle the number of animals the farmers wanted to send them.

At almost any moment in human history, this would be the highest-order crisis a human society could face: to have to slaughter your herds before summer is out because of a lack of fodder. For half a dozen generations now, we’ve lived in a world that is bound together by supply chains whose effect is to distribute the impact of any local crisis across the whole system, so that a failed harvest in the American wheat belt is more likely to cause bread riots on the streets of Cairo than on the streets of Chicago. This works until it doesn’t, until the frequency of local crises strains the global system to breaking point. In the meantime, while the system holds, it means that those whose ways of living place most strain upon the system will be the last to notice.

* * *

‘What you people call collapse means living in the same conditions as the people who grow your coffee.’

This was Vinay Gupta, on a Saturday afternoon in Llangollen in 2010, in the soulless converted sports hall of a venue where we held that first festival. It was one of those lines that everyone seemed to remember. There was talk of putting it on a t-shirt.

I realise now that I have taken consolation in such thoughts.

When Marks & Spencer put up those posters that said ‘Plan A: Because there is no Plan B’, I asked: no Plan B for who? For posh supermarkets and department stores, or for liveable human existence? Or do we no longer make the distinction?

When I wrote about Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road, it was to point out the thread of irony running through it: you’ve got this kid and his father pushing a shopping trolley down a road. In one scene, the father finds what might be the last can of Coke in the world and presents it to his son like it’s a sacrament. Isn’t there something that gets missed here, among the biblical cadences and the apocalyptic horror: the traces of a satire on our inability to imagine a liveable existence beyond the bubble of supermarkets and superhighways?

Before Dark Mountain came on the horizon, I’d read my way through the writings of Ivan Illich, from the revolutionary moment of the early seventies, when he wanted to show that ‘two-thirds of mankind still can avoid passing through the industrial age’, to the late eighties, by which time he had seen environmentalism co-opted into the oxymoron of ‘sustainable development’. And still he was able to glimpse in the fiction of Doris Lessing, or the everyday realities of his friends in the barrios of Mexico City, ‘what kinds of interrelationship are possible in the rubble’, among the ‘people who feed on the waste of development, the spontaneous architects of a post-modern future.’

In talks, I would tell the story of the Natufians. Late in the last Ice Age, in the territory marked on our maps as Israel and Palestine, they lived in year-round villages. They were among the first people anywhere to settle and they lived like this for 1,500 years, fifty generations, long enough for any memory of their ancestors’ wanderings to pass into the dreamtime of gods and culture heroes. Then came the Younger Dryas, the 1,200-year cold snap that turned Europe back to tundra and broke the pattern of the seasons which watered the wooded valleys in which they had made their homes. They knew nothing of the processes by which this climate change had come upon them; it was not a consequence of their actions, only a shift in the weather. Within a short time, they abandoned their settled way of life and became wandering gatherers and hunters, returning to the old villages only to rebury the bones of their dead in the ruins of the houses.

Then I would recall a passage in After the Ice, Stephen Mithen’s history of the prehistoric world, where I first learned about the Natufians. He sends a time-traveller to walk unobserved through the lives of the people he is writing about: coming upon a band of late Natufian nomads, he follows them to a gathering in one of the ruined villages. The interment of bones is accompanied by storytelling, feasting and celebration; the connection between past and present is reaffirmed. In Mithen’s reconstruction, these days of festival offer a respite from the hardships of the present. Yet afterwards, as the people go back out onto the land, they do so gladly: ‘They are all grateful for the return to their transient lifestyle within the arid landscapes of the Mediterranean hills, the Jordan valley and beyond. It is, after all, the only lifestyle they have known and it is the one that they love.’

These stories were never meant as lullabies. We are living through a tragedy whose measure exceeds our comprehension and most of us are implicated in this tragedy. We were born into this situation and there is no simple way to free ourselves from it. The grand summits, the uplifting rhetoric of leaders, the protests at the summit gates: none of this will make it go away. The changes we make to our lifestyles, the meat we don’t eat, the flights we don’t take: none of this will be enough. We will not make this way of living sustainable, nor anything like this way of living – and yet, I’ve always felt able to add, this need not be the end of the story. There will almost certainly be creatures like us around for a good while to come, and though they will live with the consequences of the way we lived – though their lives may be hard, as a result, in ways we do not like to think about – they will not simply live in our shadow: the way of life of those who come after us will be, just like our own, the only lifestyle they have known and the one that they love.

I stop now, as I’m writing this, to take a swig of coffee, and I try to think about the lives of the people who grew the beans, the landscape in which they were grown. I try to think about the lives of the people who assembled the computer at which I type these words, the people who mined the minerals that went into its making, the places they were taken from the ground. The conditions in which the people who grow our coffee live are not simply a default, back to which you and I might tumble should the project of civilisation (or ‘development’, as it’s known nowadays) collapse. Our lives are more entangled than that, joined by global supply chains which stretch back into the unfinished history of colonialism and its plantations, where the lives of people and plants were subject to a brutal simplification.

Still, I have taken consolation in such thoughts, in the awareness that there are vastly more ways in which humans have made life work than the lifestyle which happens to prevail around here, just now. This way of living could unravel without that being the end of the story, the end of any story worth telling. I still hold this to be true, but lately I find there are more nights when I wonder whether anything will survive the unravelling.

* * *

Mid-October. Still tired from the two-day journey back from England, my first morning home, and I’ve agreed to record an interview for the Culture show on Swedish national radio. The presenter and I sit on a bench in the park across from the railway station. He starts off asking me about the fires this summer. He’s hoping I’ll say that something has shifted as a result, but all I can think of is the stream of comments, overheard at the hairdressers or the supermarket, or around my in-laws’ dinner table, through the rainless weeks of July and August. ‘Isn’t the weather amazing?’ people would say to each other, and ‘Don’t the farmers complain a lot!’ and ‘The government should really buy more of those planes so we don’t have to keep borrowing the ones from Italy.’

After the interview, I start to wonder, though. Perhaps something has begun to shift, below the surface: a change in the conversation about climate change in certain places, a darkening realism, a movement in the boundaries of what it is possible to talk about. I’ve had some strange encounters lately with people on the inside of institutions who have lost all faith in the usual stories about how we’re going to manage this mess we’re in.

That speech last September by Guterres, the UN Secretary General, was unusually stark: ‘I’ve asked you here to sound the alarm,’ he begins. ‘If we do not change course by 2020, we risk missing the point where we can avoid runaway climate change.’ Of course, in the next breath, he is insisting that there are great opportunities ahead for green economic growth, because anything else is still unthinkable. In quiet corners, though, I’ve heard the unease of people whose job it is to put together the numbers and show how all this can be done: the need to leave the assumption of growth unquestioned is pushing them into claims that are clearly absurd. Their question is how to voice the unthinkable in a way that will have a chance of getting heard.

Here’s what I think I’m picking up, as we head into 2019: the official narratives about climate change are under strain from so many directions, there may just be a major rupture coming. Another straw in the wind is Jem Bendell’s academic paper, ‘Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy’, released in August and downloaded over 100,000 times by the end of the year. From foreign correspondents to solarpunk hackers, I keep hearing how it’s reframed the discussions going on in all these different worlds. To many Dark Mountain readers, the message of the paper won’t come as a great surprise: ‘near-term social collapse’ due to climate change is inevitable, while catastrophe is probable and extinction possible. But when this suggestion is made by a professor of sustainability leadership with twenty years’ experience working with academia, NGOs and the UN, it has a different kind of impact, at once a symptom of the shift that is underway and a contribution to that shift.

Something similar applies to Extinction Rebellion. In its framing of the situation in which we find ourselves, in the energy which has gathered around it and the speed with which all this happened, it may well be among the first movements of a new phase in the story of our collision with the realities of climate change. If this reading of the signs is anywhere near right, then there will be other movements along soon, other kinds of rupture and other kinds of work to be done.

There’s an old video from Undercurrents, the activist film network, shot in 1998 at the Birmingham G7 summit. Thousands of Reclaim The Streets protesters gather outside New Street station. On an unseen signal, the crowd spills out into the road, whistling and whooping, swarming around buses and cars, outnumbering the yellow lines of police. In the chaos of the minutes that follow, a stretch of urban freeway is occupied; part of the concrete collar of ring road thrown around the city centre by modernist urban planners in the 1950s, it’s an appropriate site for a movement that has grown out of protests against the road-building plans of the current government.

A couple of tripods have gone up, the sound systems won’t be far behind – but right now, there’s aggro up at the front, where a few vehicles are still caught inside the reclaimed zone. A man just drove his car into a small group of protesters – not at any speed, just trying to nudge them out of the way, just threatening them with half a tonne of metal – and now he’s out of the car and arguing with the police, as more protesters put themselves in front of his car, holding a banner, and now the police are letting him get back in, and now he is putting his foot down and driving straight ahead, as everyone manages to leap aside, except for one young man who is still on the bonnet of the car as it accelerates beyond the last police lines and out onto an empty dual carriageway.

I’ve never managed to track down that video, though people have assured me it exists, but I was the guy on the car, and it was only luck that meant I walked away that day with nothing worse than bruises and shock. And while it was a drama at the time, I’d hardly thought of this in years, until I saw the livestreams of the swarming protests where lines of Extinction Rebellion activists were stopping traffic at major roundabouts in London, the queues of impatient motorists, the sound of car horns.

I learned two things the day I went for a ride on a Birmingham bonnet. The first was that I am not the person you want on the frontline, when tempers are fraying and the adrenalin is rushing. There must have been ten of us in front of that car when the driver put his foot down, and the other nine all managed to throw themselves clear. I love the ones who can keep cool and make good calls in the heat of the moment, but that’s not me, and my reflexes aren’t going to come to anyone’s rescue.

Compared to the days of Reclaim The Streets, Extinction Rebellion seems strikingly sober, yet there’s still a headiness to any movement as it gathers momentum. Watching from afar, as friends use their bodies to stop vehicles, I realise that I believe in the work that they are doing and I know that there are other kinds of work that will be needed, away from the frontlines. Among that other work, there’s still a need for the space Dark Mountain holds, not least as a place to retreat and re-ground, but it’s no longer my time to hold that space: I’ve known for a while, and it’s been official since October, that I’m moving on from this project. So that brings back the old question: what do you do?

The second thing I learned that day in Birmingham was more unsettling. As the car drove off, I went chest down on the bonnet, looking into the windscreen – and then I rolled over, and he swerved to throw me off and I landed, half-running, tumbling to the ground. But in the moment before I rolled over, I remember seeing the driver’s face and knowing that he had no more clue what to do next than I had, that we were caught in a shared helplessness.

It’s the end of the year and Anna and I take a couple of weeks offline to rest and reflect. Walking beside the lake in the small town where she grew up, we talk about this sense that something is shifting, and what this means for the work that seems worth doing now, how to frame what is at stake. ‘It’s about negotiating the surrender of our whole way of living,’ I say.

There’s a thing called the Overton window, the boundary of what is ‘thinkable’ to governments and decision-makers: what you can talk about and still get taken seriously, inside the rooms where the decisions get made. I have an image of the window as a windscreen, an expression of helplessness on the face behind the glass.

Unthinkable things are going to happen, that much seems clear.

‘You should stop going round saying we’re all going to die,’ someone who spent time in those rooms told me, years ago, in an early online argument about Dark Mountain. ‘I don’t think I’ve ever gone round saying that,’ I wrote back, ‘except in the non-apocalyptic sense that, sooner or later, we are all going to die.’

There are things you can’t see clearly through that window, possibilities that go unmarked on the maps according to which the decisions are taken. We can come alive in the face of the knowledge that we are all going to die. And in the meantime, before we die, we can try to live out some of those possibilities: the ways of being human together that are hidden from view when the world is seen through the lenses of the market and the state; the ways of feeding ourselves that get overlooked because they don’t work as commodities. We can try to negotiate the surrender of our way of living, without pretending there’s any promise that this would make it all OK, without pretending we even know what OK would look like. We can have some beauty before the story is over, without pretending we can be sure how long we’ve got.

* * *

It was Anna who came up with the name – before we thought of it as a school, when we were just talking about creating a hospitable place to bring these conversations together. ‘It’s not a centre,’ she said. ‘We’re not starting a community. It’s our home, and everything else starts from there.’ It doesn’t come into being on those weeks when we advertise a public course, when people we’ve yet to meet make long journeys to be here. Those are just the times when we’re able to open up the work that’s already going on: the conversations we bring together around the kitchen table, the people who come and stay, the thinking that gets done in their company. This part of the story is clearer now than when we made that first invitation to the course last June. We’re clearer, too, about the urgency: the need for quiet spaces where bridges can be built between troubled insiders, an awakening grassroots and what one of our collaborators, Vanessa Andreotti, has taught us to think of as the ‘knowledge-carriers at the edges’; spaces of negotiation, away from the frontlines. Clearer about the role of the network we have built, our ability to bring people together and the consequences this can have. So this is our answer, just now, the place where we might have something to contribute, the work we’re going to do.

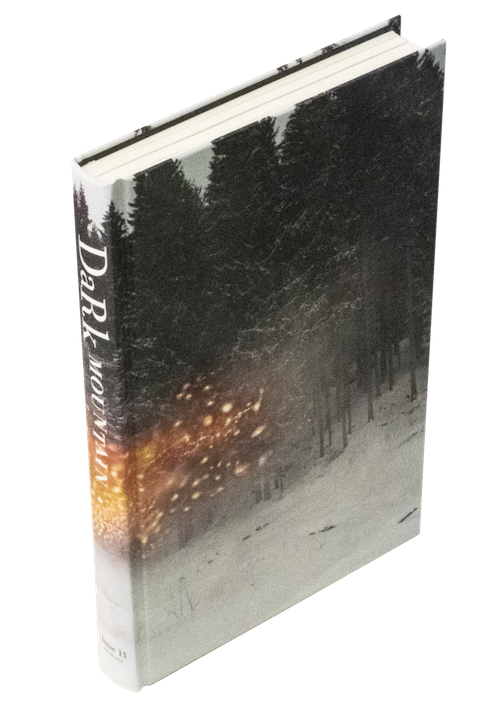

First published in Dark Mountain: Issue 15.