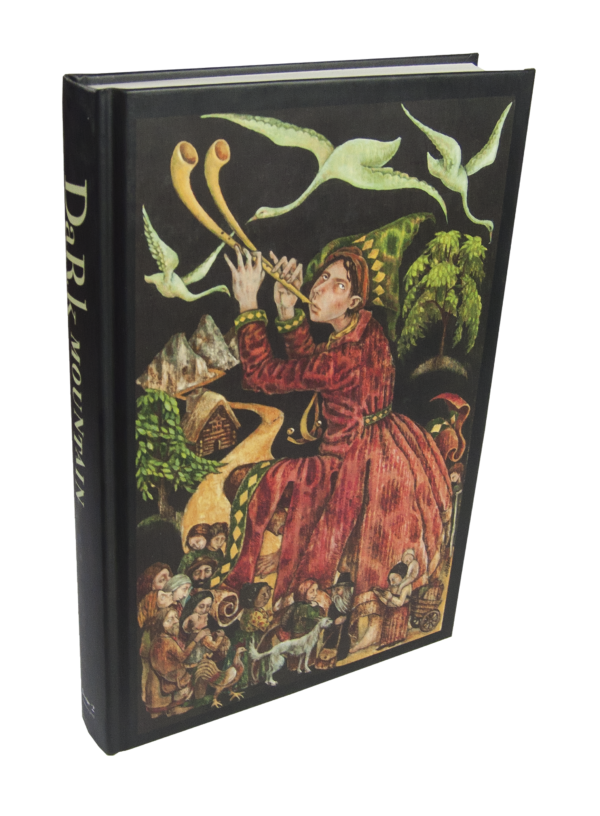

Published in Dark Mountain: Issue 2.

I am retracing my steps, trying to work out where I last saw it.

In the north of Moscow, there is a park called VDNKh. It was built in the1930s, under Stalin, and then rebuilt in the 1950s as an Exhibition of the Achievements of the National Economy. An enormous site, full of gilded statues, fountains and pavilions dedicated to different industries and domains of Soviet cultural prowess.

I don’t know in what year the exhibitions within those pavilions were last updated, but if you visit the Space pavilion, you will find a display on a dusty wall towards the back. It climbs from floor to ceiling, measuring decade by decade the achievements of the Soviet space programme. You start in the 1950s with Sputnik, then images of the Soyuz rockets, and it counts up as far as1990, and there is the Buran shuttle flying off past the year 2000, into the 21st century. By the time I made my visit, the rest of the pavilion had been put to use as a garden centre.

I am fascinated by the way that history humbles us, the unknowability of the future. It seems like a good thread to follow.

It doesn’t take a history-changing failure on the scale of the Soviet collapse to leave such Ozymandian aides-memoires. After the first Dark Mountain festival in Llangollen, I went to stay with friends in South Yorkshire. One afternoon, we climbed a fence into the grounds of a place called the Earth Centre. You can find it between Rotherham and Doncaster: get off the train at a town called Conisbrough and you walk straight down from the eastbound platform to the gates of the centre, but those gates are locked. So we walked instead around the perimeter to find the quietest and least observed place to climb over, and spent an hour or so wandering around inside.

The Earth Centre was built with Millennium Lottery funding to be a kind of Eden Project of the North. It was planned as a tourist destination and an education centre about sustainable development. It had the largest solar array of its kind in Europe, when it was built; and its gardens are wonderful now, overgrown into a vision of post-apocalyptic abundance, because the Earth Centre itself turned out not to be sustainable, in some fairly mundane ways. Unable to attract the projected visitor numbers, it closed for the last time in 2004.

I can’t think about Conisbrough without also remembering the artist Rachel Horne who comes from the town, who was born during the Miner’s Strike and whose dad was a miner. Her work and her life are bound up with the experience of a community for whom the future disappeared. She grew up in a time and a place where the purpose of that small town had gone, because the pit had closed. As she took me around the town, on my first visit, one of the saddest moments came when she pointed out a set of new houses by the railway line. ‘That’s where my dad’s allotment was.’ The allotments were owned by the Coal Board, and so when the pit closed, not only did the men lose their jobs, but also their ability to grow their own food.

Horne grew up in a school that was in special measures. Her teachers would say to her, ‘you’re smart, keep your head down, get out of here as fast as you can’. She did: when she was sixteen, she left for Doncaster to study for A-levels, and then to London to art school. She was two years into art school when she turned around and went back. The work she was doing only made sense if she could ground it in the place where she had grown up, to work with the people she knew, and make work with them. So she put her degree on hold and came home to work on the first of a series of projects which have inspired me hugely, a project called Out of Darkness, Light, in which she brought her community together to honour the memory of the four hundred men and boys who had died in the history of the Cadeby Main colliery. Led by a deep instinct for what needed to be done, she had found a way back to one of the ancient and enduring functions of art, to honour the dead and, in so doing, give meaning to the living.

When we talk about ‘collapse’, there is a temptation to imagine a mythological event which lies somewhere out there in the future and which will change everything: The End Of The World As We Know It. But worlds are ending all the time; bodies of knowledge and ways of knowing are passing into memory, and beyond that into the depths of forgetting. For many people in many places, collapse is lived experience, something they have passed through and with which they go on living. What Horne’s work underlines, for me, is the entanglement between the hard, material realities of economic collapse and the subtler devastation wrought by the collapse of meaning. This double collapse is there in the stories of the South Yorkshire coalfields, as in those of the former Soviet Union.

Yet perhaps there has already been something closer to a universal collapse of meaning, a failure whose consequences are so profound that we have hardly begun to reckon with them. In some sense, ‘the future’ itself has broken.

Looking back to the 1950s and 60s, I am struck by how, even in a time when people were living under the real threat of Mutually Assured Destruction, the future still occupied such a powerful place within the cultural imagination. It was present in a technological sense – the Jetsons visions of the future which we associate with 1950s America – and in a political sense, a belief in the possibility of a revolution that would change everything and usher in a fairer society. Or, on a quieter scale, in the creation of communities oriented around a utopian vision of making a better world.

Somewhere along the way, the future seems to have disappeared, without very much comment. It doesn’t occupy the place in mainstream culture which it did forty or fifty years ago. You can look for pivots, moments at which it began to go. The fall of the Soviet Union might be one, in a sense. ‘The End of History’ was one of the famous aggrandising labels attached to those events, but perhaps ‘The End of the Future’ would be closer to the truth? Or are we dealing with another consequence of the political and cultural hopes which hinged on the events of 1968?

Perhaps it is simpler than that. If we no longer have daydreams about retiring to Mars, is it not least because fewer and fewer people are confident that retirement is still going to be there as a social phenomenon in most of our countries, by the time we reach that age? When students take to the streets of Paris or London today, it is no longer to bring about a better world, but to defend what they can of the world their parents took for granted.

So if the future is broken, how do we go about mending it? How do were-member it, gather the pieces and put them back together? Like all griefs, the journey cannot be completed without a letting-go.

Where traces of the future remain in our mainstream culture, it is as a source of anxiety, something to be distracted from. When we, as environmentalists, talk about the future, it is often in language such as ‘We have fifty months to save the planet.’ One reason I am suspicious of this way of framing our situation is that it is so clearly haunted by a desire for certainty, and for knowing, and (by implication) the control which knowledge promises. Whereas the hardest thing about the future is that it is unknown, that history does humble us, that people often fail to anticipate the events which end up shaping their lives, on a domestic or a global scale. This isn’t an argument for ignoring what we can see about the seriousness of the situation we are in, but it is an invitation to seek a humbler relationship with the future, and to be aware of the points at which our language acts as a defence against our uncertainties. It seems to me that such a historical humility may help us navigate the difficult years ahead, and perhaps begin the process of recovering from the cultural bereavement which our societies have gone through in recent decades.

When I get up from my writing and go to the balcony of this small flat, I can see on the horizon to the north the strange landmark of the Atomium, a remnant of the World Fair held here in Brussels over half a century ago. Such structures exist in an eery superimposition, relics of a future which didn’t happen. Nothing dates faster than yesterday’s idea of tomorrow. It is remote in a way which the most mysterious and illegible prehistoric remains are not, because they were once part of the lives of people more or less like ourselves. And while it is possible that your parents or grandparents were among the hundreds of thousands who, in the summer of 1958, queued to visit the abandoned future which graces this city’s skyline, they could do so only as tourists. Those huge atomic globes have never been anyone’s sanctuary or home.

The future to which such monuments are erected has little to do with the direction history is likely to take. It represents, rather, an attempt by those who hold power in the present to project themselves, to announce their inevitability in the face of the arbitrariness of history. It is a doomed colonial move, as foolish as those rulers who from time to time have sent their armies against the sea. However confidently they set their faces to the horizon, their feet rest uneasily on the ground. History will make fools of them, too, sooner or later, arriving from an unexpected direction.

Paul Celan knew this, when he wrote:

Into the rivers north of the future

I cast out the net, that you

hesitantly burden with stone-engraved shadows.

One direction from which I have begun to find help in remembering the future is the practice of improvisation.

To understand this, it may help to start with words, to pull words to pieces in order to put them back together. ‘To provide’ is to have foresight. The word improvisation is very close to the word ‘improvident’, and to be improvident is not to have looked ahead and made provision. ‘To improvise’ turns that around, into something positive, because improvisation is the skill of acting without knowing what is coming next, of being comfortable with the unknown, with uncertainty, with unpredictability.

I have come to see improvisation as the deep skill and attitude which we need for the times that we’re already in and heading further into. Part of the truth of how climate change, for example, will play out at the level where we actually live our lives is through increased unpredictability. Less able to rely on processes and systems which we have taken for granted, we are confronted by our lack of control. This will throw us acute practical challenges, but also – as in the coalfield communities of Rachel Horne’s life and work – the challenge of holding our sense of meaning together in times of drastic change.

When you consider the history of improvisation, you encounter something like a paradox. Because it is arguably the basic human skill, the thing that we are good at. It is what we have been doing for tens of thousands of years, over meals and around camp fires, in the marketplace, the tea house or the pub. Every conversation you have is an improvisation: words are coming out of your mouth which you didn’t plan or script or anticipate. And yet we are accustomed to thinking of improvisation as a specialist skill, a kind of social tightrope-walking; this magic of being able to perform, to draw meaning from thin air, to make people laugh or make them think without having had it all written out beforehand.

Our fear of improvisation is, at least in part, a result of what industrial societies have been like and what they have done to us. I want to offer the distinction between ‘improvisation’ and ‘orchestration’ as two different principles by which people come together and do things. In these terms, we could talk about the industrial era as having been peculiarly dominated by orchestration.

Orchestration is the mode of organisation in which great amounts of effort are synchronised, coordinated and harnessed to the control of a single will. At the simplest physical level, picture the large orchestras of the nineteenth century: the coordinated movements of a first violin section are not so different to the coordinated movements of workers in a factory. The position of the conductor standing on the podium is not so different to the position of the politicians, democratic or otherwise, of the industrial era, addressing unprecedented numbers of people through new technologies which make it possible for one voice to be amplified far beyond its true reach.

The same shift away from improvisation can be seen in the basic activities of buying and selling. Think of the marketplace, a space in which economic activity is tangled up with all kinds of other sociable activities, a place for telling stories, hearing songs, catching up on news, eating, drinking, meeting members of the opposite sex (or members of the same sex). The social practices of buying and selling in the marketplace are themselves full of sociable performance. Haggling is not only a means of coming to a price, it is a playful encounter, a moment of improvisation. From there, swing to the opposite extreme, the huge department-store windows of the later nineteenth century, their shock-and-awe spectacle before which all one can do is stand silent, mouth open; just as, for the first time, it had become the convention that an audience would sit in silence in the theatre, a silence which would have been unimaginable to Shakespeare.

The story of the industrial era can be told as the story of a time in which orchestration paid off, allowing us to produce more stuff and to solve real problems. Of course, there were always challenges to be made, and around the edges we find the other stories of those who challenged the dehumanisation, the liquidation of social and cultural fabric, the counterproductivity and the ecological destruction. (Set these against the changes in life expectancy and infant mortality over the same generations, and perhaps the only human response is a refusal to draw up accounts; an assertion of the incommensurability of reality, of the need to ‘hold everything dear’.)

What we can say is that, increasingly, even within our industrial societies and the places to which they have brought us, the pay-offs of orchestration are breaking down. Systems become more complex and unstable; it becomes less effective to project the will of one person or of a central decision-making process through huge numbers of others. Under such circumstances, improvisation – the old skill edged out by the awesome machinery of Progress – may be returning from the margins.

There is another thread here, concerning time – time and desire – which could help us draw together this story of orchestration and improvisation with the question of the broken future.

Since I began talking and writing about the failure of the future, I have noticed two kinds of response, which might broadly be identified as a postmodern and a retro-modern attitude. The first shrugs ironically, ‘Worry about it later!’ A hyperreal refuge-taking in the present, in a consumer reality where styles of every time and period are mashed together with no reference to the history or the culture which produced them, in one seemingly endless now. Against this, there emerges a second, more alarmed attitude, which manifests as a kind of nostalgic modernism; a desire to reinstate the future as a thing which can inspire us, which can be a vessel for our hopes.

However desperately, sincerely or cynically they are held, it seems to me that neither of these attitudes will do. They are not up to the situation in which we find ourselves. So where else do we turn? One route to another attitude may be to say that the role of the future which characterised the modern era was never satisfactory. There was something already wrong with it. Yes, it has broken down – and the fact that people just don’t like to think about the future is part of what makes it difficult for us to motivate and inspire others to do the things we know need doing, if we’re to limit the damage we are going to live through. But the answer is not a return to the heroic striving towards the future which structured the ideologies of industrial modernity. Because that was already twisted, a tearing out of shape of time, that could only end badly.

Another story we could tell about the age of industrial modernity, of capitalism and the changing culture in which it flourished, is the story of the loss of timeliness. Max Weber saw the origins of this economic culture in the Protestant work ethic, a new emphasis on hard work and frugality as proof of salvation.3 Historians have questioned his account, but in broader terms, the journey to the world as we know it has been marked by shifts away from the sensuous and the specific, towards the abstract and exchangeable; and one of the axes along which this has taken place is our relationship to time. Not least, the shift from a world of seasonal festivals to a world of Sabbath observance marked a new detachment from the living, sensuous cycles surrounding us. (The replacement of the festive calendar with the weekly cycle also happened to offer the factory owner a more consistent return on his capital.) With this detachment from rhythm and season, there was also a loss of that sense which surfaces in the Book of Ecclesiastes, that there is a time for everything:

a time to embrace and a time to refrain from embracing,

a time to search and a time to give up,

a time to keep and a time to throw away,a time to tear and a time to mend,

a time to be silent and a time to speak,a time to love and a time to hate,

Ecclesiastes 3:5-8

a time for war and a time for peace.

This contextual, rhythmic sense of our place in the world gives way to a preference for abstract, absolute principles. The universalism which was always strong in monotheistic traditions is now let fully off the leash of lived experience, engendering new kinds of rigidity and intolerance (though also the progressive universalism which will drive, for example, the movement to abolish slavery).

Following the line of this story, we could see the history of capitalism as a history of the contortion of the relationship between time and desire. In its earlier form, to be a good economic citizen is to work hard today for a deferred reward; the repressive morality we associate with the Victorian era is then a cultural manifestation of this perpetually-deferred gratification. To push this further, perhaps the cultural upheavals of the second half of the twentieth century represent a similar knock-on effect of the lurch from producer to consumer capitalism? In the countries of the post-industrial West, to be a good economic citizen is now to spend on your credit card today and worry how you’ll pay for it later. Despite the glimpses of freedom as we pivoted from one contortion to the other, desire remains harnessed to the engine of ever-expanding GDP; only, we have switched from the gear of deferred gratification to that of instant gratification.

The cultural experiment of debt-fuelled consumption appears to be already entering its endgame. When its costs are finally counted, perhaps the loss of the future which we have been retracing will be listed among them?

Whatever stories we tell, each of them is only one route across a landscape. Some routes are wiser than others, and some are older than memory. As we turn for home, let us find our way by an old story.

Of all the figures in Greek myth, few seemed more at home in the era of industrial modernity than Prometheus. The ingenious Titan who stole fire from the gods stood as an icon of the technological leap into the future. Once again, words themselves are full of clues. Prometheus means ‘forethought’. He has a brother, whose name is Epimetheus, meaning ‘afterthought’, or hindsight. The figure of the fool, stumbling backwards, not knowing where he is going. His foolishness is confirmed when he insists, despite the warnings of Prometheus, on accepting Pandora as a gift from the gods, and with her the famous jar. And so, the story goes, came all the evils into the world. It is a deeply misogynist story; but we are not at the bottom of it. Dwelling on the name, Pandora, ‘The All-Giver’, there is the suggestion of an older path, a deeper level at which Pandora is not simply another slandered Eve, but an embodiment of nature’s abundance and our belonging within its generous embrace.v

The name of Epimetheus may long ago have been eclipsed by that of his forward-looking brother, but there is one great, unnamed, high modern icon made in his image; the figure conjured up in the ninth of Walter Benjamin’s theses on the philosophy of history:

A Klee drawing named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe that keeps piling ruin upon ruin and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

‘On the Concept of History’ (1940)

Written in the shadow of the Second World War, this is the tragic obverse of modernity’s idolisation of the future; to look backwards is always to have hindsight, and hindsight is forever useless.

But perhaps there is more to hindsight than Benjamin’s dark vision allows. Those who practice improvisation talk about the importance of looking backwards. Keith Johnstone, one of the founders of modern theatrical improvisation, writes powerfully about improvisation as an attitude to life, a mode of navigating reality. In one passage, he describes the kind of wise foolishness which it takes to improvise a story, in strikingly Epimethean terms:

The improviser has to be like a man walking backwards. He sees where he has been, but he pays no attention to the future. His story can take him anywhere, but he must still ‘balance’ it, and give it shape, by remembering incidents that have been shelved and reincorporating them. Very often an audience will applaud when earlier material is brought back into the story. They couldn’t tell you why they applaud, but the reincorporation does give them pleasure.

Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre

There is a deep satisfaction at the moment when something from earlier in the story is woven back in, for the listener and for the storyteller. In that moment, another dimension emerges, beyond the arbitrariness of linear time, and we sense the embrace of the cyclical. There is the feeling of pattern and meaning, of things coming together. The ritual has worked.

If Johnstone’s account of the craft of improvisation echoes with the footsteps of Epimetheus, in Ivan Illich’s Deschooling Society he is invoked by name. In the closing chapter of his great critique of the counterproductivity of our education systems, Illich looks towards ‘The Dawn of Epimethean Man’. The Promethean spirit of homo faber has taken us to the moon, but that was the easy part; the challenge is to find our way home, to find each other again across the aching distances our technologies have created.

Illich reminds his readers of the sequel to the myth. Epimetheus stays with Pandora, and their daughter Pyrrha goes on to marry Deucalion, the son of Prometheus. When an angered Zeus sends an earth-drowning deluge, it is Deucalion and Pyrrha who build an ark and survive to repeople the land. Writing in 1970, Illich could find resonance in this idea of a union of the Promethean and Epimethean attitudes, carrying humanity through a time of ecological disaster. Forty years on, perhaps the symmetry simply seems too neat to hold such weight.

And yet, in practical terms, I think that there may be some fragments of truth here. What gets us through the times ahead may well be those moments when we look backwards and find something from earlier in the story that we can pull through, that becomes useful again. Our leaders are very fond of talking about ‘innovation’, the point at which some new device enters social reality; we don’t seem to have an equivalent word for when things that are old-fashioned, obsolete and redundant come into their own in the hour of need. (I think of the knights in shining armour sleeping under the hill in the Legend of Alderley, as told by Alan Garner’s grandfather, and in so many other folk stories.) I think we may need such a word, because as the systems we grew up depending on become less reliable, we will find ourselves drawing on things that worked in other times and places.

There is another clue here as to why official projections of the future date so quickly. If you want to imagine what the future is going to be like, it is a mistake to assume that it will be populated by the products, tools and systems which look most ‘futuristic’, or those most marvellously optimised for present circumstances. These are the things which have been tested against the narrowest range of possible times and places. The supermarket, for example, has been with us for two generations. On the other hand, the sociable, improvisational marketplace has endured through an extraordinary range of times and places. Almost anywhere that human beings have lived in significant numbers, there have been meeting points where people come together to trade, to share news, to exchange goods, to make decisions. Just now, it may survive as a luxury phenomenon, a place to buy hand-crafted cheeses and organic vegetables. Yet the cheaper prices in Tesco this year do not cancel out the suspicion that the marketplace will continue to exist in any number of quite imaginable futures, where today’s globe-spanning systems become too expensive and unreliable to sustain the supermarket business model.

Whether we like it or not, we must live with the unknowability of the future, its capacity to humble us and take us by surprise, our inability to control it. This need not be a source of despair, nor is the choice simply between the hyperreal distractions of postmodernity and an effort to reignite the process of Progress. There is inspiration to be found in our own foolishness, stumbling backwards, muddling through, relearning the craft of making it up as we go along; cooking from the ingredients to hand, rather than starting with a recipe. If the collapse of meaning is as much of a threat as the material realities of economic and ecological collapse, not least because it debilitates us when we need all our resilience to handle those realities, then the art of finding meaning in the weaving together of past and future is not a luxury. Meanwhile, the spirit of Epimetheus should inspire us to treat the past not as an object of romantic fantasy, but nor as a dustbin of discarded prototypes. Learning how people have made life work in other times and places is one way of readying ourselves for the unknown territory north of the future, in which all our expectations may be confounded.

After all the evils of the world, one thing is left at the bottom of Pandora’s jar: hope. As Illich comments, hope is not the same as expectation. It is not optimism, or a plan. It’s not knowing what’s going to happen. But it is an attitude which enables you to keep taking one step after another into the unknown.

Johnstone never makes explicit reference to Epimetheus, but at the very end of his handbook on improvisation, he recounts three short dreams, the kind that ‘announce themselves as messages’. The last of these seems particularly familiar, like a name that is on the tip of everyone’s tongue:

There is a box that we are forbidden to open. It contains a great serpent and once opened this monster will stream out forever. I lift the lid, and for a moment it seems as if the serpent will destroy us; but then it dissipates into thin air, and there, at the bottom of the box, is the real treasure.