As things stand, I don’t believe we will get a story worth hearing until we witness a culture broken open by its own consequence.

Martin Shaw, Dark Mountain: Issue 7

The regular mechanisms of political narration are breaking down. The pollsters lose confidence in their methods, the pundits struggle to offer authoritative explanations for events that they laughed off as wild improbabilities only months before.

It’s a measure of how badly things have broken that, over the past year or two, members of the strange crew that meets around Dark Mountain have found ourselves filling the gap. I’m thinking of posts we’ve written in our various corners of the internet that were read and shared far more widely than most of us are used to, seemingly because they helped readers find their bearings in a time of deepening disorientation.

There’s a role for this kind of writing now that seems clearer than it did eight years ago, when we started this project. That’s why, today, we are launching a fundraising campaign – asking for your help to build and launch a new online publication. It won’t replace the Dark Mountain books, but it will run alongside them and provide an online home for writing that seeks – as my co-founder, Paul Kingsnorth put it at the start of this series – ‘to make sense of things, and to examine our stories in their proper perspective.’

At this point, if you want to head straight for our fundraising page and make a donation, then be my guest – but in the rest of this post, I want to make a few suggestions about why this kind of writing matters now, based on what Dark Mountain has taught me over the past eight years.

* * *

Let’s start with a few of the pieces I mentioned – the chances are you already read some of these, but setting them alongside one another, something else comes into view:

- First, here’s Anne Tagonist on ‘The Unnecessariat’, how America looks from an autopsy room in the middle of the epidemic of overdoses and suicides.

- There are a few posts I could pick from John Michael Greer’s Archdruid Report, but start with this on ‘Donald Trump and The Politics of Resentment’ (and note that it was written back in January 2016).

- Then, on the eve of the US election, there was Paul’s post on ‘The Revolutionary Moment’ – and later, kicking off this series of reflections on 2016, his ‘Year of the Serpent’.

- Also from this series, Charlotte Du Cann’s ‘The Reveal’: ‘When I switch off the machine and the headlines recede, I realise we are not in a political crisis; we are in a spiritual crisis, an existential crisis.’

- Which brings me to ‘A Counsel of Resistance and Delight in the Face of Fear’ from Martin Shaw.

- And finally, a couple of pieces of my own, both written into the raw aftermath of recent elections – first ‘The Only Way Is Down’, the morning after the UK general election of 2015 – and then ‘When the Maps Run Out’, a letter written in the days after Trump’s victory.

These are posts that got shared and reblogged and quoted and seemed to travel halfway around the internet. Mostly, they were written for our personal blogs or websites – but the authors are editors or regular contributors here at Dark Mountain. You can see places where we spark off each other’s ideas, as well as significant differences in perspective. If you read them all, you’ll probably find some that jive with you and others that jar. But I want to point to some common ground.

For one thing, while we draw on different political traditions, this is writing that starts a couple of steps back from the familiar terrain of political debate and analysis. I’m reminded of an answer I gave, years ago, when asked if Dark Mountain was a political project: ‘I think there may be times when it is necessary to withdraw from today’s politics, in order to do the thinking that could make it possible for there to be a politics the day after tomorrow.’ Or as Paul put it at the opening of this series, ‘Sometimes you have to go to the edges to get some perspective on the turmoil at the heart of things. Doing so is not an abnegation of public responsibility: it is a form of it.’

If you start exploring the work of any of these writers, you’ll find that mythology is a recurring reference point, a deep element in how we make sense of things. At the end of his post from the morning after the Brexit vote, Martin Shaw wrote, ‘Television, radio and internet will be able to tell you all the above-ground implications of what’s just taken place.’ When these surface accounts fail to satisfy, though, there’s a hunger that is fed by the underground currents of old stories.

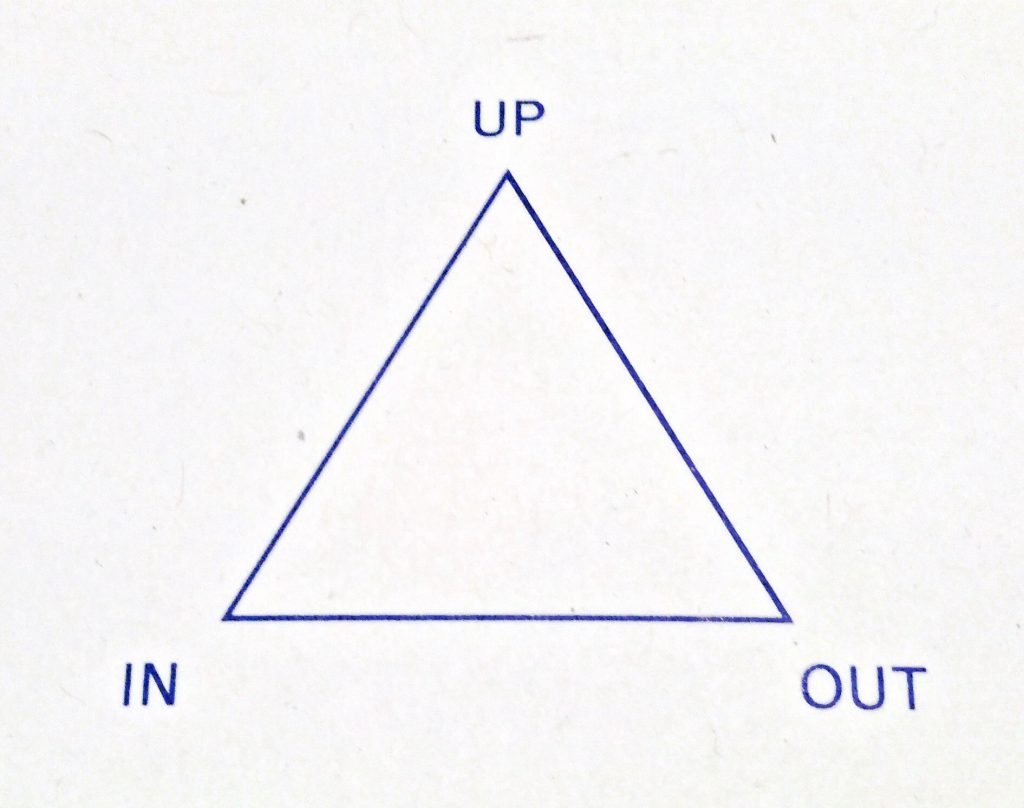

One of the things that marks out this writing, then, is a willingness to enter territory that we could call ‘liminal’. It’s a term that comes from the study of ritual, given to the middle phase of a rite of passage: the preliminaries are over, you have shed the skin of an old reality, but not yet acquired the new skin that would allow you to return to the everyday world. The liminal is the space of the threshold, with all the vulnerability and potential of transition: the costliness of letting go, with no guarantee of what will come after. The liminal phase of a ritual is the moment of greatest danger – or rather, ritual is a safety apparatus built around the liminal. Whichever, the liminal is where the work gets done, where the change happens.

So here’s the first suggestion I want to make: if this writing is filling a gap left by the failure of more conventional kinds of political narration, it’s because it is able to operate in the territory of the liminal, and these are liminal times.

* * *

It’s not just the broadening audience for this writing that points to its timeliness. The past year also saw more conventional voices getting drawn into the territory that Dark Mountain has been exploring.

Take Alex Evans, a former advisor to the UK government and the United Nations, who just wrote a book called ‘The Myth Gap’. After a career based on belief in the power of ‘evidence, data and policy proposals’, his experience of global climate negotiations brought him to a crisis, and to a sense of the need for something more than facts and reasoned arguments. ‘We’ve lost the old stories that used to help us make sense of the world,’ he says, ‘but without coming up with new ones.’ And he quotes Jung: ‘The man who thinks he can live without a myth is like one uprooted, having no true link either with the past, or the ancestral life within him, or yet with contemporary society.’

Or check out the series on ‘spirituality and visionary politics’ that the political strategist Ronan Harrington edited for Open Democracy last year – and Jonathan Rowson’s report on spirituality for the RSA. ‘Scratch climate change confusion long enough,’ writes Rowson, ‘and you may find our denial of death underneath.’

There’s lots to say about these examples, but for now I just want to take a couple of points from them. First, that the call of the liminal is making itself felt ‘above ground’. But then, that there is a danger of wanting to jump straight to rebirth, to promise bright visions and new positive narratives. Evans draws on Jung, but I’m not clear how much room there is here for the shadow – nor for the loss and uncertainty, the darkness and disorientation that are the price for entering the liminal.

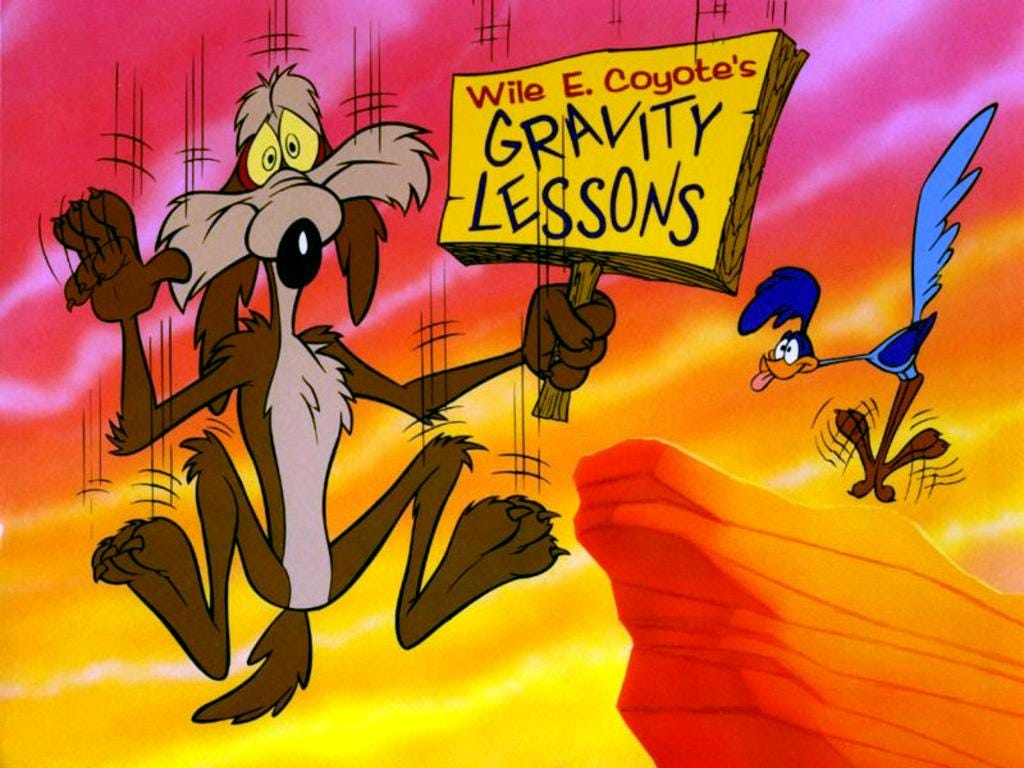

Then again, by the end of 2016, others were ready to make the descent. I once spent an hour on stage with George Monbiot pounding me over the pessimism of Dark Mountain, so it was striking to read his list of ‘The 13 impossible crises humanity now faces’. Then you had John Harris discovering Tainter’s The Collapse of Complex Societies. Watching experienced journalistic commentators move in the terrain that Dark Mountain has been exploring for the best part of a decade, it strikes me that there is another danger. To navigate at these depths, you need a different kind of equipment. Facts alone don’t cut it down here.

This brings me to the other aspect of Dark Mountain which may be crucial to finding our bearings within the liminal – the centrality of art and culture to the work of this project.

* * *

A man is whispering in your ears, disorienting you, playing tricks with your perception, even as you watch him alone on stage with little more than a few bottles of water and a cast of microphones. This is Simon McBurney’s The Encounter, one of the most staggering pieces of theatre I witnessed in 2016: a show that leads you into the story of a meeting between a photographer lost in the Amazon and a tribe whose world is under threat. Their response to this threat takes the form of a ritual, a journey to ‘the beginning’, which is also a deliberate bringing to an end of their culture in its current form.

The concept of liminality was first used to describe the structure of rituals like the one at the centre of The Encounter, but its application as a term for thinking about modern societies is connected to the study of theatre and performance. The anthropologist who made the connection, Victor Turner, distinguished the ‘liminal’ experiences of tribal cultures – in which ritual is a collective process for navigating moments of change – from the ‘liminoid’ experiences available in modern societies, which resemble the liminal, but are choices we opt into as individuals, like a night out at the theatre. This distinction comes with a suggestion that true liminality, the collective entry into the liminal, is not available within a complex industrial society.

Now, perhaps this has been true – but here’s my next wild suggestion. The consequences of that very complex industrial society are now bringing us to a point where we get reacquainted with true liminality. To take seriously not just what Dark Mountain has been talking about, but what Monbiot and Harris are touching on, is to recognise that we now face a crisis which has no outside. The planetary scale of our predicament makes it as much a collective experience as anything faced by the tribal cultures studied by Turner and his colleagues.

If this is the case, then where within our existing cultures do we go for knowledge about how to navigate the terrain of liminality? Not to the sources of factual authority, much as we need them, but to the places where liminoid practices have endured – to the arts, especially those forms in which people gather and share a live experience, and also (Turner would tell us) to those traditions and institutions that deal with the sacred.

In 2016, I came to the end of two years working as leader of artistic development with Riksteatern, Sweden’s touring national theatre. The collaboration came about because their artistic director had been strongly influenced by the Dark Mountain manifesto. In the workshops we ran together, writers, directors and performers met around the question of what art can do, in the face of all that we know and fear about the depth of the mess the world is in.

The answers that emerged began with a rejection of the usual invitation to put our art to use as a communications tool to deliver a message on behalf of scientists, policy-makers or activists – not out of some misplaced sense of ‘art for art’s sake’ purity, but because this isn’t how art works.

Instead, many of the possibilities I caught sight of during this work had to do with the liminal. Art can hold a space in which we move from the arm’s-length knowledge of facts, figures and projections, to the kind of knowledge that we let inside us, taking the risk that it may change us. Art can give us just enough beauty to stay with the darkness, rather than flee or shut down. Like the bronze shield given to Perseus by Athena, art and its indirect ways of knowing can allow us to approach realities which, if looked at directly, turn something inside us to stone. Art can call us back from strategic calculations about which message will play best with which target group, insisting on the tricky need for honesty – there’s a line I kept coming back to, from the playwright Mark Ravenhill, that your responsibility when you walk on stage is to be ‘the most truthful person in the room’. Art can teach us to live with uncertainty, to let go of our dreams of control. And art can hold open a space of ambiguity, refusing the binary choices with which we are often presented – not least, the choice between forced optimism and simple despair.

These are strange answers. For anyone in search of solutions, they will sound unsatisfying. But I don’t think it’s possible to endure the knowledge of the crises we face, unless you are able to draw on this other kind of knowledge and practice, whether you find it in art or religion or any other domain in which people have taken the liminal seriously, generation after generation. Because the role of ritual is not just to get you into the liminal, but to give you a chance of finding your way back.

Among the messages of the liminal is that endings are also beginnings, that sometimes we need to ‘give up’, that despair is not a thing to be avoided at all costs – nor a thing to be mistaken for an end state.

* * *

Somewhere in the tumbling days that followed the US election, I saw it go by in the stream of social media. ‘It’s basically Breitbart vs Dark Mountain now, isn’t it?’ someone wrote, like we’re the last ones left whose worldviews aren’t in smithereens after the year that just happened. And like a few things in 2016, it had the taste of a bad joke that might have more truth in it than you’d want to be the case.

In the last weeks of the year, as we were putting together this series of reflections, a discussion got started among the Dark Mountain editors about what the role of this project should be, in the years ahead. Bad jokes aside, it’s clear that the work we’ve been doing has taken on a new relevance, and with that comes a sense of responsibility.

A couple of things are clear. The books we publish will always be at the heart of this project – and the work of artists, the makers of culture, will always be our starting point.

Every year, thousands of copies of our books go out to readers around the world. By the standards of an independent literary journal, it’s an achievement, and it’s through the sale of our books that we’re able to pay for some of the work that goes into Dark Mountain. (The rest of the work, as you can imagine, is a labour of love.)

A sobering realisation this autumn, though, was that the audience coming to this website each year is a hundred times the size of the number of people ordering the books. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course – but over the years, we’ve given only a fraction of the attention to this site that goes into each of our print issues.

So we came to the conclusion that it’s time to do something online that comes closer to the richness of the books we publish (and will go on publishing). Exactly what form this takes, we’re still working on – but it’s going to be an online publication, something more and different to a blog – and a site that reflects more of the web of activity of the writers, thinkers, artists, musicians, makers and doers who have taken up the challenges of the Dark Mountain manifesto.

To make this happen, we need your help.

We’re asking for donations to cover the costs of building and launching a new online home for Dark Mountain. You can send a one-off amount, or set up a small monthly subscription – or if you’d like to talk about other forms of support, then you can get in touch. Everything you need to know is here, on our new fundraising campaign page.

How ambitious we can be with the next phase of Dark Mountain depends on the level of support we get, so at this stage we’re not setting a fundraising target or a deadline – but we’ll tell you more as we go along.

Meanwhile, thank you for reading and sharing the work we publish. From the crowdfunding of the manifesto onwards, everything Dark Mountain has done over the years has been made possible by the support of friends, collaborators and readers. We don’t take that for granted – and wherever things go next, however dark it gets, we’re thankful for the journey we’ve been on with you.

Published on the Dark Mountain website as the closing essay in a series reflecting on the political events of 2016 — and to launch the campaign that crowdfunded the new online edition of Dark Mountain. Over the following six months, we succeeded in raising over £37,000 to fund the creation of a new online edition which launched in June 2018.