It was September and I hadn’t seen Ruben all summer, but there he was, the same as ever, gangly and lounging, his hair cropped almost to the bone, his eyes alert; a kid from the wrong side of town who turns the skills his childhood taught him into art. That summer, I’d become a father. The weeks of July and August tightened into the small world of our new family, living by old rhythms of bodily need. (I must have said something about this – about the way it shatters whatever illusions you had of your own centrality, how it locks you into the chain of generations and releases you from any compulsion to make your one life a story in itself.) And I asked him, ‘So, how was your summer? What have you been up to?’

‘I gave my sermon on the mount,’ he said, like it was a matter of fact, and it turned out that it was.

One Friday night, 150 mostly young people had followed him up a rocky hill on the edge of town (the town where he grew up, an hour south of Stockholm) to where the birch trees clear, and they sat on the ground and listened as he spoke. There were no flowing robes; he wore an Adidas tracksuit top and carried a binder with his notes. He wasn’t playing the messiah, trying to start a cult; nor was he playing the artist, making a point by appropriating the forms of religion. As the sun went down over the pines, he talked about life as a journey through the woods at dusk, each of us carrying a pocket-light of reason: its beam cuts a bright tunnel, but throws everything outside this tunnel into darkness; if we use it thoughtlessly, we forget that we have other senses with which to find our way.

When the sermon and the discussion that followed were at an end, the congregation made their way quietly down among the trees, the twilight deepening around them.

* * *

A few years before, I had made a book with the video artists Robert and Geska Brečević, who operate as Performing Pictures. Around the time we met, their work took an unexpected turn as they began collaborating with craftworkers in Oaxaca and Croatia, building roadside chapels and producing video shrines that set the saints in motion. Our book was a document of this work but also an enquiry into how it came about, what had drawn them to the folk Catholicism of the villages where they were now working, and the reactions this had provoked among their art-world contemporaries. About these reactions, I wrote:

We are used to art that employs the symbols of religion in ways seemingly intended to unsettle or provoke many of those to whom these symbols matter. Yet to the consumers of contemporary art, those who actually visit galleries, it is more uncomfortable to be confronted with work in which such symbols are used without the frame of provocation.

That may still be the case, yet these days I am struck by how many of the artists, writers and performers I meet find themselves drawn to the forms and practices of religion.

I think of Ben who went off to Italy to start an ‘unMonastery’, a working community of artists in service to its neighbours. The name suggested a desire to distance themselves from the example of the religious community, even as they found inspiration there. A couple of years facing the difficult realities of holding a community together, however, deepened their appreciation for the achievement of those who had maintained monasteries for generations, and this was reflected in a series of conversations which Ben went on to publish with abbots of established religious orders.

For some, it’s a question of taking on the roles religion used to play, using the tools of ritual to address the ultimate. When I run into Emelie, a choreographer friend, she’s just back from a small town in the middle of Sweden where a group of artists has taken over the old mine buildings. It’s the kind of place that lost its purpose with the passing of the industry which called it into being. The project started with two brothers who grew up there – and this weekend, they have been celebrating the younger brother’s birthday. The way I hear it, the celebration was a three-day ritual which saw participants building their own coffins only to be lowered into them, emerging after several hours to be greeted with music and lights and a restorative draught of vodka.

In another mining town a thousand miles away, Rachel Horne made her first artwork at the site of the colliery where four generations of her family had worked. Out of Darkness, Light was a memorial event: one night on the grassed-over slag heap above the town, 410 lamps were lit, one for each of the men and boys who died in the century in which coal was mined there. On a boat travelling along the river below, a group of ex-miners and their children told their stories. This was art as ritual, honouring the dead in such a way as to bring meaning to the living.

Last time I spoke to Rachel, we talked about an event that she had put on a few weeks earlier. ‘You know,’ she said with a sigh, ‘it was like organising a wedding!’ I knew: months of energy building up to a big day and afterwards everyone involved is exhausted. Weddings are great, but how many do you want to have in a lifetime? It hit me, as artists we’re good at ‘weddings’, but sometimes what’s called for is the simplicity of the weekly Sunday service. Soon afterwards, I came to a passage in Chris Goode’s The Field and the Forest where he quotes a fellow theatre-maker, Andy Smith:

Every week my mum and dad and some other people get together in a big room in the middle of the village where they live. They say hello to each other and catch up on how they are doing informally. Then some other things happen. A designated person talks about some stuff. They sing a few songs together. There is also a section called ‘the notices’ where they hear information about stuff that is happening. Then they sometimes have a cup of tea and carry on the chat.

Both Smith and Goode are impressed by the resemblances between the Sunday service and the kinds of space they want to make with theatre. The connection is not made explicit, but when Goode ends his book with a vision of a ‘world-changing’ theatre where ‘once a fortnight at least, there’s someone on every street who’s making their kitchen or their garage or the bit of common ground in front of their estate into a theatre for the evening’, I think back to that passage and the distinction between the wedding and the weekly service.

* * *

I could go on for a while yet, piling up examples, but it’s time to pull back and see where this might get us. The artists I’ve mentioned are all friends, or friends of friends, so I can’t pretend to have made an objective survey. I don’t even know if such a survey could be made, since much of what I’m describing takes place outside the official spaces of art. Even the objects produced by Performing Pictures, though they sometimes hang in galleries, are made to be installed in a church or at a roadside.

There is nothing new, exactly, about artists tangling with the sacred – indeed, the history of this entanglement is the thread I plan to follow through these pages. Yet here in the end-times of modernity, under the shadow of climate change, I want to voice the possibility that these threads are being pulled into a new configuration. There’s something sober – pragmatic, even – about the way I see artists working with the material of religion. The desire to shock is gone, along with the skittering ironies of postmodernism; and if ritual is employed, it is not in pursuit of mystical ecstasy or enlightened detachment, but as a tool for facing the darkness. I’m struck, too, by a willingness to work with the material of Western religious tradition, with all its uncomfortable baggage, rather than joining the generations of European artists, poets and theatre-makers who found consolation in various flavours of orientalism.

All this has set me wondering: what if the times in which we find ourselves call for some new reckoning with the sacred? What if art is carrying part of what is called for? And what if answering the call means sacrificing our ideas about what it means to be an artist?

A Strange Way of Talking About Art

We have been making art for at least as long as we have been human. Ellen Dissanayake has made a lifelong study of the role of art within the evolution of the human animal, and she is emphatic about this:

Although no one art is found in every society … there is found universally in every human group that exists today, or is known to have existed, the tendency to display and respond to one or usually more of what are called the arts: dancing, singing, carving, dramatizing, decorating, poeticizing speech, image making.

Yet the way such activity gets talked about went through an odd shift about 250 years ago. In Germany, France and Britain, just as the Industrial Revolution was getting underway – and with colonialism pushing Western ideas to the far corners of the world – a newly extravagant language grew up around art. The literary critic John Carey offers a collage of this kind of language, drawn from philosophers, artists and fellow critics:

The arts, it is claimed, are ‘sacred’, they ‘unite us with the Supreme Being’, they are ‘the visible appearance of God’s kingdom on earth’, they ‘breathe spiritual dispositions’ into us, they ‘inspire love in the highest part of the soul’, they have ‘a higher reality and more veritable existence’ than ordinary life, they express the ‘eternal’ and ‘infinite’, and they ‘reveal the innermost nature of the world’.

Bound up with this new way of talking is the figure of the artistic genius. There have always been masters, artists whose skill earns them a place in the memory of a culture. In his account of the classical Haida mythtellers, the poet and linguist Robert Bringhurst is at pains to stress the role of individual talent within an oral literature, where a modern reader might expect to encounter the nameless collective voice of tradition. Yet a fierce respect for mastery does not presuppose a special kind of person whose inborn capacity makes them, and them alone, capable of work that qualifies as ‘art’. Rather, as Dissanayake shows, in most human cultures, it has been the norm for just about everyone to be a participant in and appreciator of artistic activity.

The ideas about art which took hold in Western Europe in the late 18th century spread outwards through cultural and educational institutions built in Europe’s image. Were anyone to point out their peculiarity, it need not have troubled their proponents, for the contrasting ideas of other cultures could be assigned to a more primitive phase of development. Today, that sense of superiority has weakened and become unfashionable, although it remains implicit in much of the thinking that shapes the world. Under present conditions, a critic like Carey can take glee in mocking the heightened terms in which Kant and Hegel and Schopenhauer wrote about art; yet the result is a deadlocked culture war in which defenders of a high modern ideal of art are pitched against the relativists at the gates.

Rather than pick a side in this battle, it might be more helpful to ask why art and the figure of the artist should take on this heightened quality at the moment in history when they did. If a new weight falls onto the shoulders of the artist-as-genius, if the terms in which art is talked about become charged with a new intensity, then what is the gap which art is being asked to fill?

That the answer has something to do with religion is suggested not only by the examples which Carey assembles, but also by the sense that he is playing Richard Dawkins to the outraged true believers in high art. And there have been those, no doubt, for whom art has played the role of religion for a secular age. But this hardly gets below the surface of the matter; the roots go further down in the soil of history. It is time to do a little digging.

The Elimination of Ambiguity

In 1696, an Irishman by the name of John Toland published a treatise entitled Christianity Not Mysterious. This was just one among a flurry of such books and pamphlets issuing from the London presses in the last years of the century, but its title is emblematic of the turn that was taking place as Europe approached the Enlightenment: a turn away from mystery, ambiguity and mythic thinking.

As the impact of the scientific revolution reverberated through intellectual culture, the immediate effect was not to undermine existing religious beliefs but to suggest the possibility of putting them on a new footing. If Newton could capture the mysterious workings of gravity with the tools of mathematics, then the laws governing other invisible forces could be discovered. In due course, this would lead to a mechanical account of the workings of the universe, stretching all the way back to God.

In its fullest form, this clockwork cosmology became known as deism: a cold reworking of monotheistic belief, offering neither the possibility of a relationship with a loving creator, nor the firepower of a jealous sky-father protecting his chosen people. The role of the deity was reduced to that of ‘first cause’, setting the chain reaction of the universe in motion. Stripped of miracles, scripture and revelation, deism never took the form of an organised religion or gained a substantial following. It attracted many prominent intellectual and literary figures in England, however, in the first half of the 18th century, before spreading to France and America, where it infused the philosophical and political radicalism which gave birth to revolutions.

The religious establishment recoiled from deism and its explicit repudiation of traditional doctrine. Yet mainstream Christianity was travelling the same road, accommodating its cosmology to the new science in the name of natural theology, applying the tools of historical research to its scriptures and seeking to demonstrate the reasonableness of its beliefs. The result was a form of religion peculiarly vulnerable to the double earthquake which was to come from the study of geology and natural history. Imagine instead that the rocks had given up their secrets of deep time to a culture shaped by the mythic cosmology of Hinduism: the discovery would hardly have caused the collective crisis of faith which was to shake the intellectual world of Europe in the 19th century.

To this day we live with the legacy of this collision between naturalised religion and the revelations of evolutionary science; militant atheists clash with biblical literalists, united in their conviction that the opening chapters of Genesis are intended to be read as a physics and biology textbook. It is an approach to the Bible barely conceivable before the 17th century.

* * *

Mystery can be the refuge of scoundrels; ambiguity, a cloak for muddle-headedness. The sacred has often been invoked as a way of closing off enquiry or to protect the interests of the powerful. We can acknowledge all of this and deplore it without discarding the possibility that reality is – in some important sense – mysterious. It takes quite a leap of faith, after all, to assume that a universe as vast and old as this one ought to be fully comprehensible to the minds of creatures like you and me.

Among the roles of religion has been to equip us for living with mystery. This is not just about filling the gaps in current scientific knowledge or offering comforting stories about our place in the world. Across many different traditions there is an underlying attitude to reality: a common assumption that our lives are entangled with things which exceed our grasp, which cannot be known fully or directly – and that these things may nonetheless be experienced and approached, at times, by subtler and more indirect means.

This attitude shows up in the deliberate strangeness of the way that language is used in relation to the sacred. The thousand names of Vishnu, the ninety-nine names of Allah: the multiplication of such litanies hints at the limits of language, reminding us that words may reach towards the divine but never fully comprehend it. A similar effect is achieved by the Tetragrammaton, the four-letter name of God in the Hebrew Bible, written without vowels so as to be literally unspeakable.

For Christians, a classic expression of this attitude to reality appears in Paul’s first letter to the church at Corinth, from the chapter on love that gets read at weddings:

When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (1 Corinthians 13:11–12)

The emphasis is on the partial nature of knowledge: in relation to the ultimate, our understanding is childlike, a dark reflection of things we cannot see face-to-face. The most memorable of English translations, the King James Version gives us the image of a ‘glass’, but the mirror which Paul has in mind would have been of polished brass. Indeed, it is carefully chosen, for the Greek city of Corinth was a centre for the manufacture of such mirrors.

The thought that there are aspects of reality which can be known only as a dark reflection calls up another Greek image. The myth of Perseus is set in motion when the hero is given the seemingly impossible task of capturing the head of the Gorgon Medusa, whose gaze turns all who look on her to stone. The goddess Athena equips Perseus with a polished shield; by the reflection of this device, he is able to approach the monster, hack off her hissing head and bag it safely up. In the shield of Perseus we glimpse the power of mythic thinking: by way of images, myth offers us indirect means of approaching those aspects of reality to which no direct approach can be made.

Few passages in the Bible are more at odds with the spirit of the Enlightenment than Paul’s claim about the limits of human knowledge. To put away childish things was the ambition of an age in which the light of reason would shine into every corner of reality. What need now for dark reflections – or mythic shields, for that matter? By the turn of the 18th century, such things were no longer intellectually respectable: the unknown could be divided into terra incognita, merely awaiting the profitable advance of human knowledge, and old wives’ tales that were to be brushed away like cobwebs.

The institutional forms of religion were capable of surviving this turn away from mystery, though much was lost along the way, and none of the later English translations of the Bible can match the poetry of the King James. Meanwhile, if anyone were to go on lighting candles at the altars of ambiguity, it would be the poets and the artists, the ones upon whose shoulders a new weight of expectation was soon to fall.

Toys in the Attic

When the educated minds of Europe decided that humankind had come of age, the immediate consequence for art was a loss of status. If all that is real is capable of being known directly, then the role of images and stories as indirect ways of knowing can be set aside, relegated to entertainment or decoration.

I say immediate, but of course there was no collective moment of decision; we are dealing rather with the deep tectonic shifts which take place below the surface fashions of a culture, and the extent to which the ground has moved may be gauged as much through the discovery of what was once and is no longer possible, like the epic poem. The pre-eminent English poet of the first half of the 18th century, Alexander Pope aspired to match the achievement of Milton’s Paradise Lost by producing an epic on the life of Brutus; yet, despite years of telling friends that the project was nearing completion, all that he left upon his death was a fragment of eight lines. The failure seems more than personal, as though the mythic grandeur of the form was no longer available in the way it had been a lifetime earlier.

In Paris in 1697, a year after Christianity Not Mysterious had rolled off the London presses, Charles Perrault’s Histoires ou contes du temps passé launched the fairy tale genre, committing the stories of oral tradition to print with newly added morals. By the time the first English translation was printed in 1729 – ‘for J. Pote, at Sir Isaac New-ton’s Head, near Suffolk Street, Charing Cross’ – the publisher could advertise Perrault’s tales as ‘very entertaining and instructive for children’. Stories which had been everyone’s, which carry layers of meaning by which to navigate the darkest corners of human experience, had now been tamed and packed off to the nursery.

Meanwhile, a strange new form of storytelling arose which put a premium on uneventful description of the everyday and regarded unlikely events with suspicion. ‘Within the pages of a novel,’ writes Amitav Ghosh, ‘an event that is only slightly improbable in real life – say, an unexpected encounter with a long-lost childhood friend – may seem wildly unlikely: the writer will have to work hard to make it appear persuasive.’ A masterful novelist himself, Ghosh is nonetheless troubled by the 18th-century assumptions encoded within the form in which he writes. What troubles him most is the thought that these assumptions underlie the failure of the contemporary imagination in the face of climate change.

In the kinds of story which our culture likes to take seriously, all of the actors are human and most of the action takes place indoors. Such realism is ill-equipped to handle the extreme realities of a world in which our lives have become entangled with invisible forces, planetary in scale, which break unpredictably across the everyday pattern of our lives. The writer who wants to tell stories that are true to this experience had better go rummaging in the attic where the shield of Perseus gathers dust among the toys, the sci-fi trilogies devoured in teenage weekends and the so-called children’s literature where potent materials exiled to the nursery grew new tusks.

But writer, beware: the boundaries of the serious literary novel are still policed against intrusions of myth or mystery, and the terms used to police them are telling. In notes for a never-finished review of Brideshead Revisited, written on his own deathbed, George Orwell marks his admiration for Waugh as a novelist, but then comes the breaking point: ‘Last scene, where the unconscious man makes the sign of the Cross … One cannot really be Catholic and a grown-up.’ Almost half a century later, Alan Garner met with the same charge when his novel Strandloper was published as adult literary fiction. The Guardian’s reviewer, Jenny Turner, found the author guilty of crossing a line with his insistence on depicting Aboriginal culture on its own terms:

… such a phantastic view of history cannot ever rationally be made to stand up. This underlying irrationality usually works all right in poetry, which no one expects to make a lot of sense. It’s okay in children’s writing, which no one expects to be psychologically complex. But in a grown-up novel for grown-ups, it just never seems to work.

Carrying the Flame

As Paganini … appeared in public, the world wonderingly looked upon him as a super-being. The excitement that he caused was so unusual, the magic he practised upon the fantasy of the hearers so powerful, that they could not satisfy themselves with a natural explanation.

So wrote Franz Liszt on Paganini’s death in 1840. The Italian violinist and composer had been the model of a virtuoso: a dazzling performer who stuns audiences with technical audacity and sheer force of personality. The term itself had taken on its modern meaning within his lifetime, shaped by his example. In those same years, an unprecedented cult of personality grew up around the Romantic poets, while in the theatres of Paris and London a strange new convention had emerged, according to which audiences sat in reverential silence before the performers; half a century earlier, theatres were still such rowdy spaces that an actor would be called to the front of the stage to repeat a favourite speech to the hoots or cheers of the crowd.

A new sense was emerging of the artist as a special category of human. The conditions for this had been building for a long time. In ‘Past Seen from a Possible Future’, John Berger argues that the gap between the masterpiece and the average work has nowhere been so great as within the tradition of European oil painting, especially after the 16th century:

The average work … was produced cynically: that is to say its content, its message, the values it was nominally upholding, were less meaningful for the producer than the finishing of the commission. Hack work is not the result of clumsiness or provincialism: it is the result of the market making more insistent demands than the job.

Under these conditions, to be a master was not simply to stand taller than those around you, but to be looking in another direction. In the language of Berger’s essay, such masterworks ‘bear witness to their artists’ intuitive awareness that life was larger’ than allowed for in the traditions of ‘realism’ – or the accounts of reality – available within the culture in which they were operating. Dismissed from these accounts were those aspects of reality ‘which cannot be appropriated’.

Berger warns against making such exceptions representative of the tradition: the study of the norms constraining the average artist will tell us more about what was going on within European society. Still, exceptionality of achievement fuelled the Romantic idea of the artist set apart from the rest of society. If the Enlightenment established lasting boundaries around what it is intellectually respectable for a ‘grown-up’ to take seriously, then the Romantic movement inaugurated a countercurrent which has proven as enduring. In Culture and Society, Raymond Williams identifies a constellation of words – ‘creative’, ‘original’ and ‘genius’ among them – which took on their current meanings in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, as part of this new way of talking about the figure of the artist.

The artists themselves were active in creating this identity. Here is Wordsworth, in 1815, addressing the painter Benjamin Haydon:

High is our calling, Friend! – Creative Art …

Demands the service of a mind and heart

Though sensitive, yet in their weakest part

Heroically fashioned – to infuse

Faith in the whispers of the lonely Muse

While the whole world seems adverse to desert.

Keats’ formulation of ‘Negative Capability’, the quality required for literary greatness, is among the clearest statements of the role which now falls to the artist, a figure who must be ‘capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.’

* * *

I have been making a historical argument, though it is the argument of an intellectual vagabond who goes cross-country through other people’s fields. Since we are now coming to the height of the matter, let me take a moment to catch my breath – and recall an earlier attempt at covering this ground, made in the third chapter of the Dark Mountain manifesto:

Religion, that bag of myths and mysteries, birthplace of the theatre, was straightened out into a framework of universal laws and moral account-keeping. The dream visions of the Middle Ages became the nonsense stories of Victorian childhood.

The claim towards which I have been building here is that those elements which became increasingly marginalised within respectable religious and intellectual culture by the middle of the 18th century found refuge in art. In many times and places, and perhaps universally, the activity of art has been entangled with the sacred, with the rituals and deep stories of a culture, its cosmology, the meaning it finds or makes within the world – and all of this wound into the rhythms which structure our lives. What is new in the historical moment around which we have been circling is the sense that the sacred has passed into the custody of art: insomuch as it dwells with mystery, ambiguity and mythic thinking, it now fell to the artist to keep the candle alight. Here, I submit, is the source of the peculiar intensity with which the language of art and the figure of the artist is suddenly charged.

* * *

If art has carried the flame of the sacred through the cold landscapes of modernity, it has not done so without getting burned. The scars are too many to list here, but I want to touch on two areas of damage.

First, the roles assumed by artists over the past two centuries have overlapped with those which might in another time or place have been the preserve of a priest or prophet. In a culture capable of elevating an artist to the status of ‘super-being’, there is a danger here: the framework of religion may remind adherents that the priest is only an intermediary between the human and the divine, but there are no such checks in the backstage VIP area. The danger is that the show ends up running off the battery of the ego instead of plugging in to the metaphysical mains. Even when an artist sees her role as a receiver tuned into something larger than herself, without a common language in which to speak of the sacred, the result may be esoteric to an isolating degree. How much of the self-destruction which becomes normalised – often romanticised – as part of the artistic life can be traced to the lack of a stabilising framework for making sense of the mysteries of creative existence?

Another danger arises from the exceptional status of the artist. While the reality of artistic life is often precarious, there exists nonetheless a certain exemption from the logic which governs the lives of others: the artist is the one kind of grown-up who can move through the world without having to explain their rationale, whether monetary, vocational or otherwise. In theory, at least, if you can get away with calling yourself an artist, you will never be required to demonstrate the usefulness, efficiency or productivity of your labours. Where public funding for the arts exists, if you can prove your eligibility, you may even join the privileged caste of those for whom this theory corresponds to reality. (And you may not: ‘performance targets’ for funded arts organisations can be punishingly unreal.)

The danger of the artistic exception is that it serves to reinforce the rule: get too comfortable with your special status as the holder of an artistic licence and you risk sounding at best unaware of your privilege, at worst an active collaborator in the grimness of working life for your non-artist peers. (Arguably, the only ethical model of artistic funding is a Universal Basic Income, which is how many young writers, artists and musicians approached the unemployment benefits system of the UK as recently as the 1980s.)

Begin Again

And here we are, back in the early 21st century, where the legacies of the Romantics and the Enlightenment are both persistent and threadbare. We don’t know how to think without them, and yet they seem out of credit, like a congregation that attends out of habit rather than conviction, or not at all.

A few years back, there was a fire at the Momart warehouse in east London. Among the dozens of artworks that went up in smoke were Tracey Emin’s tent and the Chapman brothers’ Hell. John Carey has some fun setting the reactions of callers to radio phone-ins against all those high-flown statements about the spiritual value of art: ‘Only in a culture where the art-world had been wholly discredited could the destruction of artworks elicit such rejoicing.’

Under these conditions, do I truly propose to lay a further weight on the shoulders of my artist friends – to charge them with the task of reconfiguring the sacred? Not quite.

If art gave refuge to the sacred and served as its most visible home in a time when it was otherwise scoured from public space, I believe the time has come for art to let it go. In the world we are headed into, it won’t be enough for an artist caste to be the custodians, the ones who help us see the world in terms that slip the net of measurable utility and exchange. One way or another, the ways of living which will be called for by the changes already underway include a recovery of the ability to value those aspects of reality which cannot be appropriated, which elude the direct gaze of reason, but which so colour our lives that we would not live without them.

This is not a call for a new religion, nor for a revival of anything quite like the religions with which some of us are still familiar. I have met the sacred in the stone poetry of cathedrals and the carved language of the King James Bible, but buildings and books never had a monopoly. For that matter, art was not the only place the sacred found shelter, nor even the most important – though it was the grandest of shelters and the one that commanded most respect, here in the broken heartlands of modernity. Out at the places we thought of as the edges, there were those who knew themselves to be at the centres of their worlds, and who never thought us as clever as we thought ourselves. Even after all the suffering, after all the destruction of languages and landscapes and creatures, there are those who have not given up. But if we whose inheritance includes the relics of Christianity, Enlightenment and Romanticism have anything to bring to the work that lies ahead, then I suspect that one of the places it will come from is the work of artists who are willing to walk away from the story of their own exceptionality.

And though I know that I am drawing simple patterns out of complex material, it seems to me that something like this has begun, at least in the corners of the world where I find myself. I don’t think it is an accident that several of the artists I have invoked here returned to work in the towns where they grew up; the pretensions you picked up in art school are not much use on the streets where people knew you as a child.

Unable to appeal to the authority of art, you begin again, with whatever skills you have gathered along the way and whatever help you can find. You do what it takes to make work that has a chance of coming alive in the spaces where we meet, to build those spaces in such a way that it is safe to bring more of ourselves. This does not need to be grand; you are not arranging a wedding. A group of strangers sits around a table and shares a meal. A visitor tells a story around a fire. You half-remember a line you heard as a child, something about it being enough when two or three are gathered together.

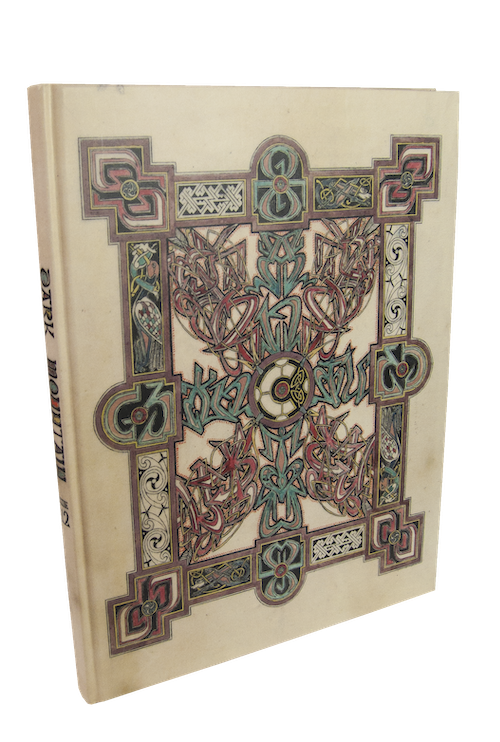

Published in Dark Mountain: Issue 12 ‘SANCTUM’, a special issue on the theme of ‘the sacred’.