So, good morning. I’m afraid it’s true: that nightmare you had, it wasn’t a dream. Let yourself feel the shock, the rawness of disappointment sharpened by sleep deprivation. If you ached for an end to five years of government by the rich, for the rich, then what you are feeling today is a blow to the soul. Stay with that for a while, before the pundits and the candidates in the coming leadership elections start to rationalise what just happened. There are other levels on which we need to make sense of this cruel result.

Labour is about to endure a tug of war between those who believe it needs to go leftwards and those who believe it needs to go rightwards. The truth is, neither of these directions will be much help. Right now, the only way is down.

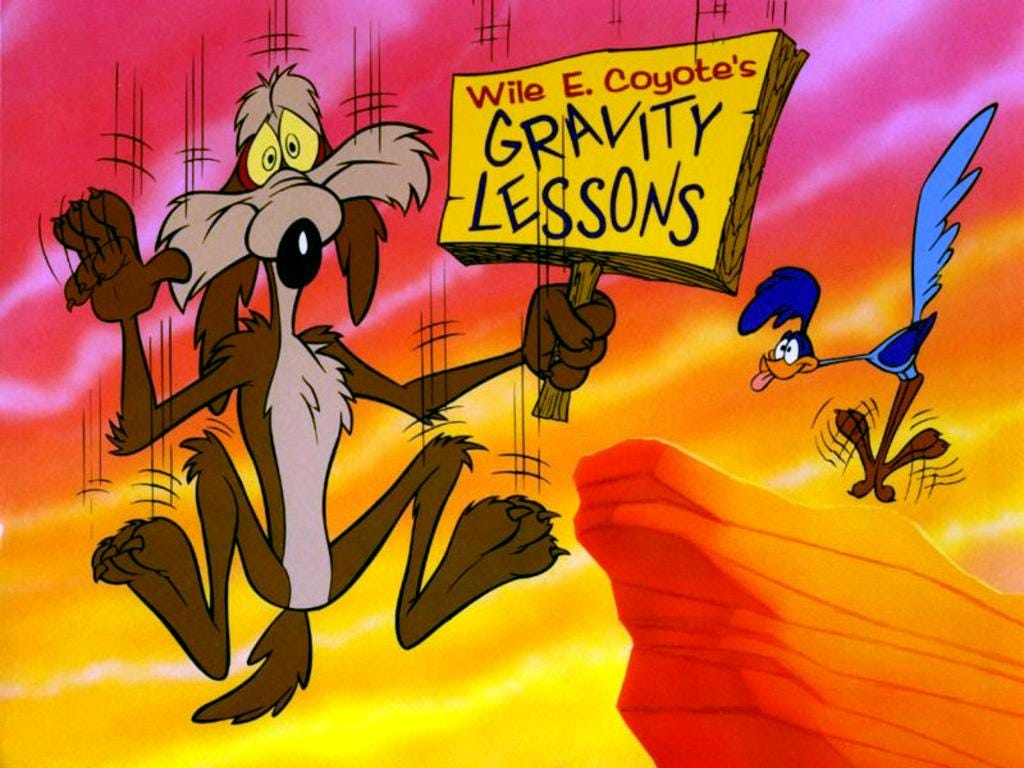

What we have seen is a failure of politics, a failure of democracy at a cultural level, part of a larger story playing out across the struggling countries of the post-industrial west. For now, it may look like the Tories have won, but it is a fragile victory. If you want an image for the state of English politics today — Scotland is another story — then think of three cartoon characters who have run off a cliff. Two of them have just plummeted and flattened themselves into the ground, while the third is still hanging there, feet spinning in the air, oblivious to its situation.

The one cold comfort that Labour — and perhaps even the Lib Dems — could take from last night’s results is that events have forced them into a confrontation with reality, while the Tories will continue to govern on the basis of delusions, with ugly results, for a while longer, before gravity catches up with them. This could give the defeated parties a head start, but only if they are prepared to enter into a kind of soul-searching deeper than anything we have seen in British politics in a very long time.

For that to have a chance of happening, it will have to start somewhere else, somewhere beyond the party machines and the earnest, highly-educated, decent people at the centre of them, who are almost entirely unequipped for the journey to the political underworld which is now called for.

What follows are a set of notes that might help us get our bearings for this journey, some of which may turn out to be wildly off the mark. But I hope they are some use, this morning. Take care of each other. Give someone a hug today. Look out for the moment where you catch a stranger’s eyes and recognise the loss you have in common, a loss that goes deeper than the tally of seats. Grieve for the inadequacy of the ways in which we have tried to stand up to greed and fear and exploitation. But hold your disillusionment gently, don’t let it harden into damning conclusions about human nature. Get ready for a dark ride ahead. We are going to have to rethink politics on a level this election didn’t touch.

Everything is broken

1. Three tribes go their separate ways. About the only piece of commentary from the election campaign that felt truly prescient last night was Paul Mason’s analysis of the fragmentation of the UK into three distinct political geographies: a Scotland dreaming of a future as the warm south of Scandinavia, a south-east held up by asset wealth, and a post-industrial remainder of the union. There is no party that is now a major contender in all three parts of the country and their divergence means that there is no unified pattern of swing at a national level.

2. Labour talked to five million people, but it didn’t know how to listen.The sincere bewilderment of Labour figures as the exit poll turned out to be accurate says something about the failure of the “ground campaign” in which activists had five million doorstep conversations over the past four months. How do you talk to that many people and come away having misread the mood of the country this badly? Two easy answers will be given to this: Labour talked to the wrong people and/or people didn’t tell them the truth. There’s probably truth in both of these, but there’s a third reason that goes to the deeper levels of what just happened: the conversations they had on the doorsteps weren’t real conversations. We badly need new ways of having political conversations — and if we’re to start regrowing a democratic culture from below, it will start with finding ways to bring such conversations together.

3. The Lib Dems totally misunderstood their own voters. One of the most striking features of the night was the splintering of their vote in every direction: in some constituencies, it appeared to be dividing equally between Labour, Tory, UKIP and Green candidates. Some collective delusion convinced the Lib Dems that their MPs had earned the loyalty of local voters. It seems truer to see the party as having been a depository for vague dissatisfaction of a variety of flavours, whose raison d’etre disintegrated when they became an adjunct to the Tories.

4. People who are into politics just don’t get how puzzling and alienating it looks to the rest of the population. This is a broader version of the problem the Lib Dems had. Over the past week, I’ve worked with the #dontjustvote tour, a tiny playful art project making its way across the south of England on its way to Westminster, starting conversations about the election in all the places they stopped along the way. The stories they gathered along the way, snatches of which you can find on their Facebook and YouTube pages, brought home to me the sheer confusion, mistrust and disconnect with everyday reality which is most people’s experience of politics.

5. Social media is not delivering on its promises to change politics.There are lots of reasons for this, including that many of the promises were hype. But here’s one element in the mix. If you’re old enough to remember when Google was new, then think back to the first time you saw the Google search page: how long did it take before you got why it was good? Not much longer than a few keystrokes and a click. Then think back to the first time you saw Twitter: how long did it take you before you got why it was good? Probably months. Or maybe you’re still not convinced. The social technologies that have grown up over the past decade layer a depth of social and cultural subtlety on top of the technical platform in a way that wasn’t true for the information technologies of the internet in its earlier phases. This creates an under-recognised gap between the people who have invested the time to get initiated in the kind of active, engaged use of a tool like Twitter and people who don’t get it and aren’t likely to get it any time soon. So it’s not just the self-selecting echo chambers we create that make social media problematic, it’s also the unrepresentative section of the population who are actively present there and the detachment this fosters from the rest of the population.

6. Is it time to ditch the expensive American advisors? Hell yes!When I was a broke student, I spent my summers selling educational books door-to-door for a US company, first in the UK and then in California. Nothing prepared me for the difference in psychology between how Brits like to make “buying decisions” and how Americans do. Just because we share a common language, doesn’t mean American experts are well-placed to help British politicians.

A 200-year moment?

7. The unmaking of the English working class. The long trend underlying all of this is the unravelling of the social settlement that slowly emerged from the Industrial Revolution, from the destruction of pre-industrial ways of living to the emergence of the labour movement to the social democratic consensus of the mid-20th century. We have inherited political parties that belonged to a kind of society we no longer live in. As I rushed out the door yesterday morning, I found myself grabbing E.P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, a pre-history of the labour movement that covers the period between 1790 and 1830. The period we’re in has many resemblances to that. (If I were a cartoonist, I’d be tempted to draw Cameron as the Prince Regent…) None of the forms of left-wing politics that we’ve inherited are adapted to the times in which we find ourselves — and the process of regrowing a democratic culture is, I suspect, going to require a search for new and unexpected political forms that resembles the history that Thompson tells. The roots of the popular political movements that grew up in the 19th century were deeply entangled with grassroots self-education movements — and something equivalent to this is going to be needed in the years ahead.

8. The British media make a joke of democracy. A handful of tax-avoiding billionaires control the agenda of almost all the national papers which then indirectly controls the agenda of the broadcasters. The grip of a cynical and decadent establishment is another feature that’s reminiscent of the period Thompson describes — and the creation of new grassroots media was part of the process that led to the emergence of the labour movement.

9. Love him or hate him, Russell Brand might just be our William Cobbett… It’s neither a precise analogy nor an unambiguously positive one, but Cobbett found a voice that captured the popular imagination, speaking in dramatic language about the monstrousness of the times. He was also a fantastic egoist. “Cobbett’s favourite subject, indeed, was William Cobbett,” writes Thompson. “But… his egotism transcended itself to the point where the reader… is asked to look not at Cobbett, but with him.” (I don’t know whether Cobbett also swigged from over-sized bottles, but if he did they probably weren’t full of water.)

10. Brand provides a clue to the only kind of revolution that is still even conceivable. The week he went on Newsnight and predicted a revolution, I’d been in England, giving a lecture about “the failure of the future”, in which I suggested that one of the symptoms of this was the impossibility of taking seriously the idea of political revolution in the way that had still seemed possible in the 1960s. As the video went viral, I wondered if I was wrong. And then I remembered something Martin Shaw says, one of his mythic metaphors for making sense of the kinds of times in which we’re living: “This isn’t a hero time, this isn’t a goddess time, it’s a trickster time.” When people like John Berger (one of my heroes) were young, it was a real thing to believe in the heroic revolution that Marx had seemed to promise. Today, the only kind of revolution that is plausible is a foolish one, one where we accidentally stumble into another way of being human together, making a living and making life work. (And whatever that might look like, it doesn’t look like utopia.)

A journey to the underworld

11. This is not just a battle of ideas, it is a battle for the soul.Another thing that Brand is onto, in his inimitable way, is what he would call the “spiritual” nature of the revolution. Margaret Thatcher was explicit about how deep the project of neoliberalism went. Two years into her first term, she told the Sunday Times:“Economics is the method: the object is to change the soul.” The left has never taken this seriously, we have never even tried to contest neoliberalism on the territory of the soul. The people at the top of today’s Labour party, a few of whom I’ve crossed paths with over the years, are in no way equipped to operate in the territory of the soul — so it’s probably going to take the help of some of us who’ve been a long way outside the pale of politics-as-we-know-it, if we’re going to work out how to do this. But one of the wrong notes that Miliband hit in the past few weeks, for all his decency and awkward charm, was his repetition that this election was “a clash of ideas”. The political battle in which we are engaged is deeper than that, it’s a battle for the soul, and until the left feels that, I don’t think it will find its way to the kind of new politics we are going to need.

12. We need to be willing to go to some dark places. I had a public conversation last summer with Steve Wheeler in which he sketched out a set of thoughts about the need for a politics of “depth”. I must edit the recording and get it online, but the thrust of it was that the left has associated depth and the darker, less rational side of ourselves with the worst kind of politics. His argument — which parallels the one Zizek makes about Nazism in his Perverts’ Guide to Ideology — is that it’s a terrible mistake to cede the territory of the intuitive, the emotional, the unconscious, the irrational to the far right. It’s only by people of good will engaging with these sides of ourselves, at a cultural as well as an individual level, that we can prevent a political “return of the repressed”. We need to go there vigilantly, but we need to go there.

13. We need to understand the amount of fear in the equation.Miliband used to talk about the “squeezed middle”, but it turns out the Tories can still count on the worried middle. As I’ve said before, there aren’t enough people doing well in Britain to deliver a Tory majority, but there are enough people who are worried, who hope the brittle prosperity of the housing bubble will sustain their way of living a little longer, who hope that what happened to the poor, the young and the disabled over the last five years won’t happen to them. The puzzlement I see in the despairing posts of friends on Facebook over the past twelve hours comes, I think, from the difficulty we have in understanding this. Somehow, we need a space for conversations where people can speak honestly about their fears, their disillusionment, their lack of belief in the possibility of change for the better — without trying too hard, too quickly to convince them they are wrong. Presenting big ideas or retail policies is no substitute for this.

Regrowing a democratic culture from below

14. Democracy doesn’t end at the ballot box. The aftermath of the Scottish referendum proved this, wrong-footing the entire UK establishment. Below the surface, barely capable of being translated into election results (except in Scotland), there is an extraordinary welling of anger, disillusionment, disgust with the lot of them. I wouldn’t like to predict the circumstances in which this will take louder, more visible shape, but it was one of the running themes that emerged from the #dontjustvote tour. The Scottish precedent needs to be the inspiration for an ongoing grassroots process of democratic renewal.

15. This needs to start outside of politics as we know it. Politics today is broken in ways that go deeper than our political institutions or the people who inhabit them are able to reach. While the kind of regrowth of a democratic culture that I’m talking about is not non-partisan in some detached, objective way, it can’t be on behalf of any one party, either.

16. Build a movement that starts by being present in the place where you are and supporting the most vulnerable. Look at the role that the grassroots movements around Syriza have played in helping people to endure the hardships of austerity in Greece. That needs to be one of the models for whatever happens in Britain, as five more years of austerity are piled on the weakest. And for heaven’s sake, work with the churches (and the mosques, synagogues, gudwaras and temples) — whatever the rational differences many on the left may have with people of faith, the everyday engagement of religious communities puts most of us to shame. And the churches have shown more courage in criticising austerity than most of the Labour frontbench.

17. Another party is possible. The FPTP system may be a steep obstacle, but we live in strange times. Look at the polls in Spain. Look at the polls in Iceland, one of the few countries hit harder than the UK by the banking crisis — they are now in the third (or fourth?) act of some kind of political revolution, where a left outsider coalition gave way to a centre right government, but that government is now losing support as the Pirate Party lead the opinion polls. Strange times, really.

18. Come to Sweden (but lose your illusions). I’m writing these notes in Gothenburg Central station, about to rush off to the Congress of the “popular movement” that owns the national touring theatre for which I currently work. Since the exit polls came out last night, I’ve had a stream of people, with varying degrees of seriousness, asking me if they should move to Sweden. I wish I could help you fulfil your wishes, but there are far more similarities between the reality of politics today here and the British situation than you would like to believe. The work that needs to be done here is much the same as the work that needs to be done there — though, for now, the harshening grip of neoliberalism is better hidden here, and we have been spared the kind of austerity the UK has seen. But precisely because the work that needs doing is similar, maybe there are possibilities to host conversations here that bring together people from both countries who want to engage in this work. I’m certainly interested in helping to make that happen.

Alright, enough words. Be kind to each other. And be wary of the tendency to allow a situation to be defined by the oppositions present within it. This is going to be a time for redrawing the maps, a time when things we overlooked or undervalued may end up making all the difference.

First published on my old blog, the morning after the UK general election of 2015.